From the Laboratory to the Bedside

FORMA FLUENS

Histories of the Microcosm

From the Laboratory

to the Patient’s Bedside

Iatrochemistry between

Franciscus Sylvius and Reiner De Graaf

Alessio Dore

University of Turin

Comèl Grant

This article aims to analyse the contribution of Franciscus Sylvius (Franz de le Boë, 1614-1672) to the definition of iatrochemistry and to the identification of its uses in combating disease: by focusing on the way in which he reformulates traditional concepts through the lenses of chemistry, I try to show how such ideas are put to the test through clinical practice and experimentation, both by Sylvius himself and by his pupil Reinier de Graaf (1641-1673), in order to find new treatments for diseases.

Historical Context

Sylvius’s activity is situated within a phase of profound renewal of European medicine, which, over the course of the seventeenth century, witnessed a rethinking of its theoretical and practical foundations through the integration of clinical observation, anatomical dissection, and chemical experimentation.

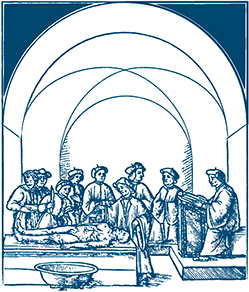

A central role in this process was played by the University of Leiden, founded in 1575: already by the seventeenth century, it was one of the main European centres for medicine, thanks to an education that combined solid theoretical foundations with a form of didactic innovation. Indeed, academic training did not remain confined within lecture halls, but took place in an environment rich in instruments and spaces for practice: the botanical garden [Figure 1], the anatomical theatre, the pharmaceutical laboratory, and the city hospital [1].

In this context, a form of medicine open to experimentation and to the comparison between different approaches flourished. Among its protagonists were professors and physicians who turned Leiden into a laboratory of ideas, among whom Sylvius stands out – among others – for having given particular impetus to iatrochemistry, one of the most original and influential currents of seventeenth-century medicine.

After having studied medicine and philosophy in Sedan, Sylvius moved to Leiden, where he came into contact with Adolphus Vorstius and – upon returning after obtaining his doctorate in Basel – was appointed to the chair of anatomy [2]. Here, through dissections of cadavers, he sought to confirm the nature of disease and to establish the effectiveness of treatment: starting from the traditional conception according to which health depends on the proper balance of bodily fluids, Sylvius’s innovation consists in the idea that healing occurs through the administration of chemical remedies [3]. Disease would arise when this balance breaks down, with an increase either of bodily acids or of alkalis.

The Body as a Chemical Laboratory

Sylvius’s ultimate aim is to definitively dispense with obsolete practices such as bloodletting or the use of Galenic medicines, instead administering drugs prepared chemically through fermentation or maceration: by means of these procedures, the arcanum – the essence of a substance – is freed from the inert matter that surrounds it [4]. Far from being a magical or esoteric element, the arcanum may rather be conceived as the active principle of a substance.

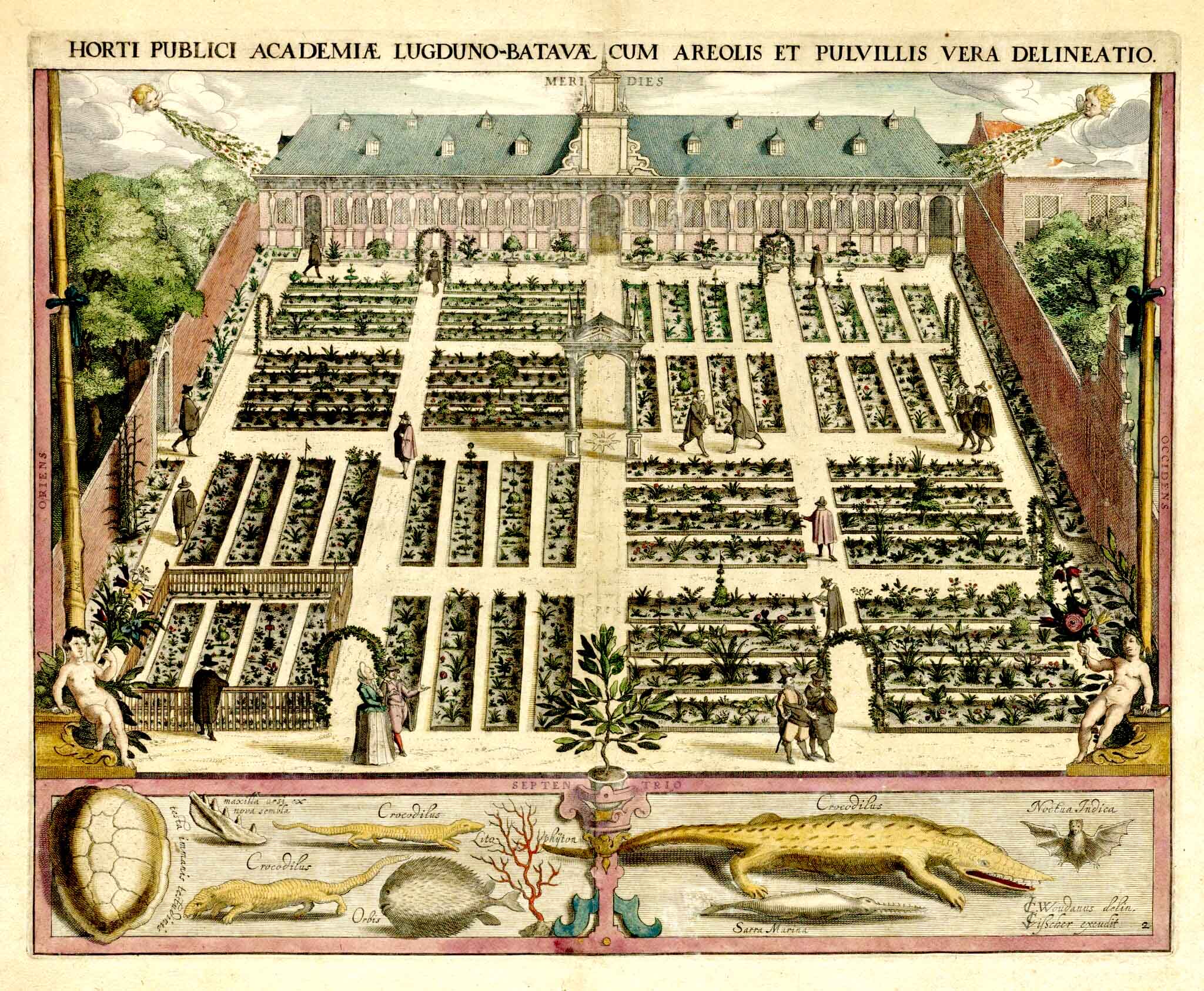

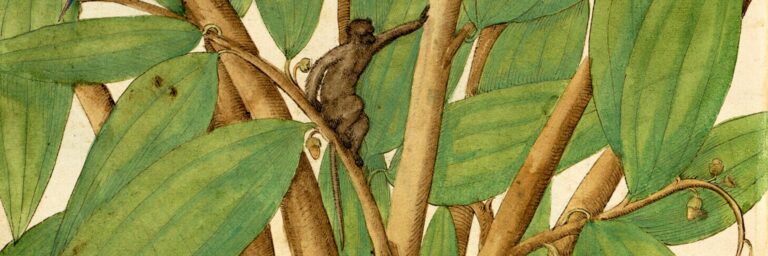

In the De methodo medendi [Figure 2], Sylvius devotes entire sections to the properties of substances such as the hydragogue, the phlegmagogue, and the cholagogue – medicines that were supposed to purify water, phlegm, and bile – indicating the foods in which they can be found and recognising their usefulness in purging the organ concerned. The cholagogue, for example, is present in large quantities in tamarind, in the juice of white and purple roses, in peach blossoms, in rhubarb, and in aloe; for each of these substances, the most effective mode of administration is indicated (some are better dissolved in wine, others are preferably eaten as pulp), in order to induce vomiting and rid the body of excess bile [5]. A central role is thus assigned to the processes involved in digestion, since it is through it that chemical substances enter the body and interfere with its functioning.

Figure 1. Leiden Botanical Garden.

Figure 2. Sylvius’s Medical Work.

The purpose of digestion is to separate the useful parts of food from the useless ones, and the body accomplishes this task by destroying the bonds between the elements that make up the ingested substances [6]. Sylvius posits two different types of bonds: one generated by salt, which can easily be dissolved with the aid of water, and one by oil, which, being insoluble in water, can only be destroyed by fire; for this reason, the requirements of fermentation – on which the entire digestive process is based – are water and heat [7]. In this respect, Sylvius shows himself indebted to Van Helmont, who – following the Paracelsian tradition – conceives digestion as a fermentative process, no different from what an alchemist can produce in the laboratory using an alembic and a furnace, recognising the role of acids in the stomach that cause ingested substances to ferment, transforming them into new elements (transubstantiating them) [8]; subsequently, in the duodenum, this acidic mixture undergoes a further fermentation through the action of the salts contained in bile, which allows the digestive process to continue [9].

Iatrochemistry as a Therapeutic Remedy

However, anchored to his time, Van Helmont was unable to explain why nutrients are selected and waste products rejected, and thus resorted to vitalism, introducing the archeus, a spiritual principle that presides over material phenomena and directs the digestive process; Sylvius, by contrast, takes a step forward and speaks of chemical affinities inherent in materials, the same affinities that allow iron to replace the copper contained in the acidic spirit of vitriol [10].

Alessio Dore obtained an MA in Philosophy from the University of Turin, with a thesis on mechanism and free will in Descartes and Regius, under the supervision of Professor Paola Rumore. He subsequently earned a second MA in History, supervised by Professor Andrea Strazzoni, with a thesis on the dissemination of Cartesian medicine in the Netherlands. He currently teaches Italian and history at secondary school and is enrolled in an MA program at the University of Turin entitled Expert in Educational and Didactic Processes in Schools.

It is on these themes that the Praxeos medicae idea nova opens. Hunger is explained through chemistry: food residues in the stomach, upon coming into contact with ingested saliva, ferment and emit a pleasant acidic substance, which stimulates the upper orifice of the stomach – probably the cardia – producing the sensation of hunger [11].

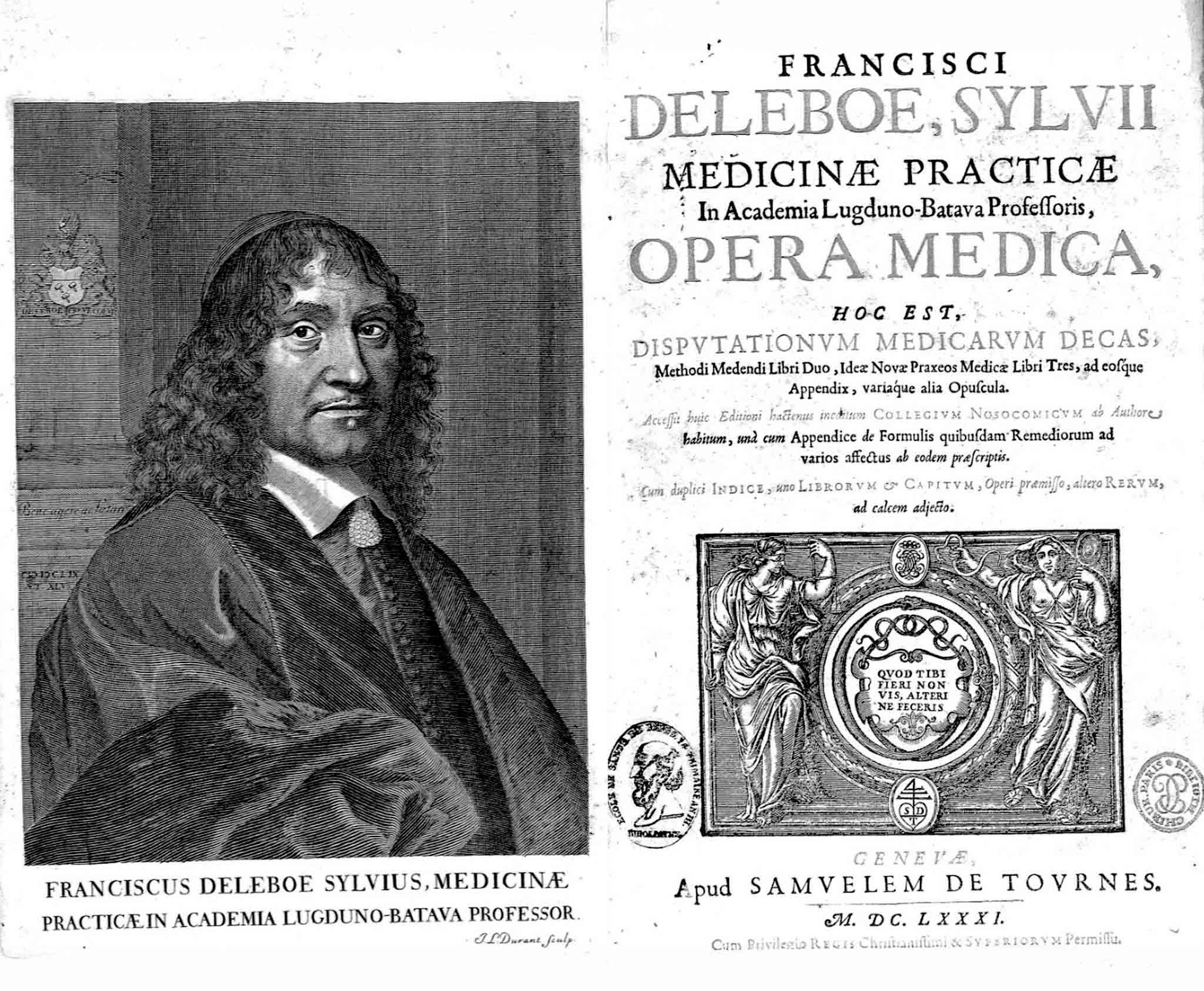

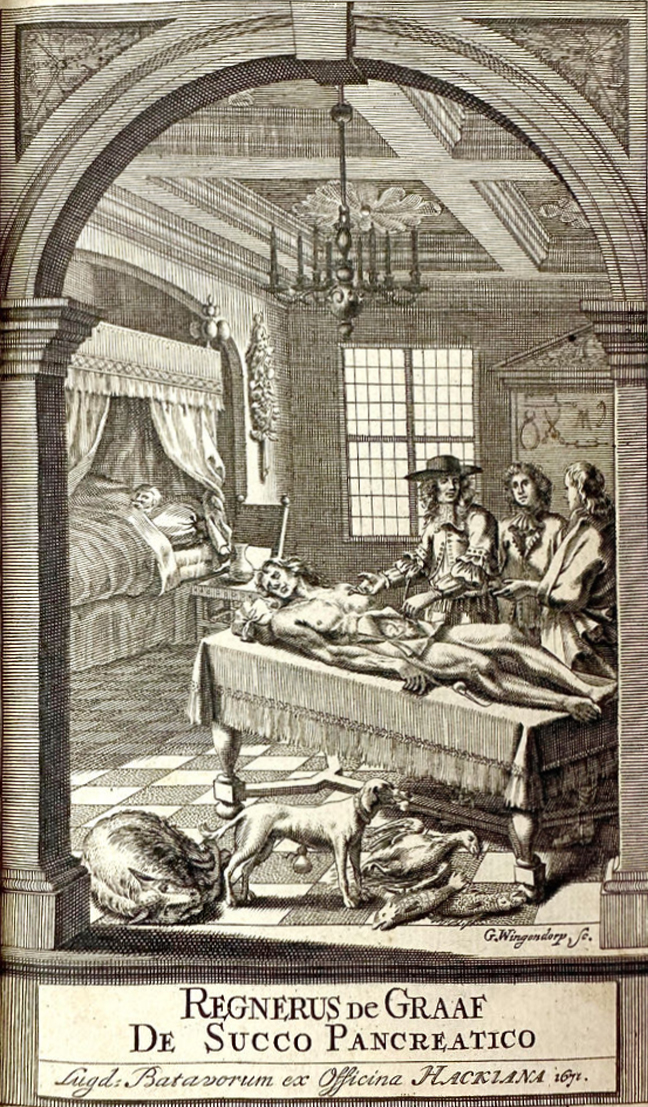

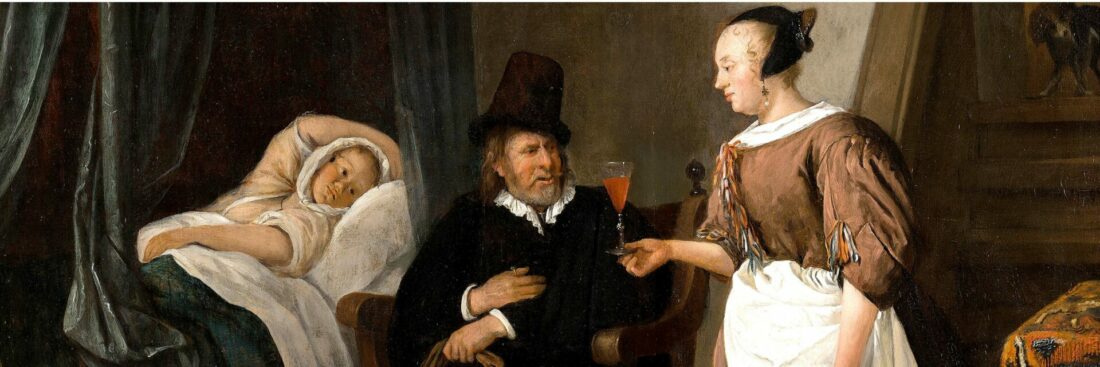

Moreover, in this work Sylvius associates each disease with a specific remedy, for which he provides the recipe, including the correct dosages for preparation and indicating the modes of administration: the chemical properties of officinal herbs can in fact restore health by acting on the balance of the body’s humours [12]. By teaching medicine directly in the hospital, Sylvius is able to test these solutions on patients, examining their effectiveness. Nevertheless, experimentation does not stop at the administration of relatively safe drugs to human beings. His pupil De Graaf, in order to confirm Sylvius’s hypothesis according to which the plague behaves like a volatile alkaline substance, injects alkaline salts into the veins of dogs and observes that they cause internal haemorrhages: the same symptoms occur when contracting the plague [Figure 3] [13].

De Graaf’s Experiments

De Graaf’s experiments, conducted according to the autoptic method of his teacher Sylvius, are meticulously described in the De Succo Pancreatico. Here, the author seeks to explain the role of the pancreas by presenting his findings after carrying out dissections on dogs, cats, monkeys, horses, and humans, employing a comparative method that allows him to note differences between the organs of different species and to understand the reason for such variability, thereby establishing functional generalisations [14] [15].

Moreover, by collecting pancreatic juice, De Graaf experimentally confirms Sylvius’s hypotheses: the effervescence produced in the intestine arises from the mixture of this secretion (acidic) and bile (basic) [16]. Departing from the Galenic tradition, which relied on sight and touch to classify and recognise different substances, De Graaf makes use of the sense of taste to catalogue different chemical substances, and it is through this sense that he discovers the acidity of gastric juices [17]. Van Helmont did the same, distrusting Galenic physicians who were accustomed to identifying the presence of bile in urine simply by its colour, instead urging that it be tasted in order to perceive its bitterness sensorially [18].

The frontispiece of the De Succo Pancreatico clearly shows the conception on which medical knowledge was based for both its author and his teacher [Figure 4]. We can observe De Graaf depicted as showing two colleagues the contents of the abdominal cavity; dogs are present, and, in the background, a patient can be seen lying on a couch [19]. The image represents what, for Sylvius, are the three principles on which medical knowledge must rest: the dissection of cadavers, experiments on animals, and the examination of the patient [20]. Sylvius, in fact, goes daily to examine his patients in order to monitor the development of the disease and the effect of medicines (chemical remedies); his pupils, who accompany him on these rounds, participate actively and, through dialogue, propose the diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy [21].

Conclusion

The analyses of Sylvius and De Graaf confirm that iatrochemistry was not merely an abstract theory, but an approach concretely applied to the treatment of disease. Their conceptions of the functioning of the body, experiments on animals, and use of chemical remedies illustrate the attempt to translate traditional concepts such as digestion, the balance of humours, and disease into procedures based on chemistry. In this way, the theoretical framework of iatrochemistry is continually put to the test in clinical practice, allowing the effects of remedies to be observed directly.