Medicine in the Homeric World

FORMA FLUENS

Histories of the Microcosm

Healing in the Homeric World

Uncovering Medical Knowledge in the 'Iliad' and 'Odyssey'

Luca Lippoli

University of Bologna

It was in the second half of the eighth century BCE that the Iliad and Odyssey, the oldest surviving Greek literary works, took the form that, except for a few interpolations, we know today. Following Schliemann’s archaeological excavations, it has been widely recognised that their historical background is not purely fictional, though many of their elements remain imaginary and anachronistic. However, they also reflect knowledge and practices contemporary to the time of their composition rather than to earlier periods, some of which may have been informed by historical inquiry into past customs. Drawing on a plot preserved through oral tradition, Homer’s genius was capable of creating a dazzling world where gods, heroes, and ordinary mortals engaged in a variety of activities. In this world, the common order of things merges with the marvellous, the everyday with the sublime. It is within this interplay that medical references emerge.

War, Gods, and Epidemics

From the very first lines of the Iliad,[1] we are drawn into a world overshadowed by rage and ruin. A pestilence (loimós) sweeps through the Achaean camp, a silent yet merciless scourge, intertwined with the wrath (mēnis) of Achilles—the mightiest of warriors, now burning with fury after Agamemnon seizes back his prize, the slave Briseis. These twin calamities—disease and anger—set the stage for a tale steeped in destruction.

It is possible to put forward some hypotheses regarding the disease referenced in the preface of the Iliad, the defence strategies employed in cases of epidemics, and the ontological conception of disease in Greek culture during the Homeric period, particularly in relation to notions of guilt and divine punishment. Homer does not provide direct indications of the nature of the disease afflicting the Achaeans, nor does he dwell on possible symptoms. This omission reflects the fact that much of the etiology of epidemics and diseases at the time was almost entirely absent, as seen in the generalised nomenclature, which lacked clear distinctions or classifications.

However, one detail should not be overlooked, as it may help identify the disease rampant in the Achaean camp—or at least the one Homer intended to evoke—namely, its divine origin in Apollo Smintheus. This epithet, originally associated with a pre-Hellenic deity, was later attributed to Apollo and linked to sminthios, meaning “mouse.” Consequently, Apollo was also honoured as “the exterminator of mice.” This information suggests that the disease in question may have been the plague, despite the poem’s lack of precise nomenclature or etiological knowledge. Alternatively, it could have been an infectious disease of bacterial origin, caused by the Yersinia pestis bacillus.[2] The reference to mice is significant, as historically, the bacillus is primarily carried by various species of rodents, with its main vector being the rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis). However, transmission could also have occurred through other parasitic species, such as fleas, lice, and bedbugs, or even from human to human. In the latter case, additional symptomatic details would have been crucial in refining the diagnosis with greater precision.

The Iliad also offers a meticulous and tireless depiction of death, with Homer unafraid to repeat his most significant expressions in describing how every vital principle (thymós) and the soul (psychē) abandon the bodies of the fallen. A dark cloud envelops the dying; their nostrils no longer draw breath; their sight falters, and their eyes are veiled by a black night; their knees give way, and they collapse into unconsciousness; they fall into a heavy sleep, and life exhales from their mouth or from a bitter wound. This attention to detail allows for an analysis of possible symbolic conceptions of life and death. Although beliefs in an afterlife and a separation between soul and body—psychē and thymós—existed, the archaic Greeks of the Homeric world may also have developed a more modern and unambiguous view of death: one understood simply as the cessation of life, rather than as a transition to a parallel existence governed by the gods and destiny. In this perspective, Homeric thought seems to convey a sombre resignation in the face of death rather than a hopeful expectation of its continuation.

The Trojan War: an Example of Anatomical Topography

The Iliad also provides an analytical description of the circumstances of death for many of the over two hundred fallen, most of them warriors identified by name who perished on the battlefield. In the majority of cases, death results from trauma sustained in combat. In accordance with the themes of the two poems, martial violence occupies significantly more space in the Iliad than in the Odyssey. From a medical perspective, the descriptions in the Odyssey are often summary and formulaic. In contrast, the author of the Iliad depicts a large number of wounds with notable anatomical precision—and not without a certain relish—offering a vivid and detailed account of the injuries sustained by the warriors who clashed beneath the walls of Troy. In a sense, these descriptions constitute the earliest known surgical report on battlefield casualties.

Charles Daremberg first explored this approach in 1865,[3] methodically examining the Iliad to establish, with great caution, the numerical distribution of wounds according to the affected areas of the body. He systematically reviewed the locations of injuries (e.g., six deaths from wounds to the cranial vault, seven from frontal injuries, three from wounds to the temple, etc.). In 1879, the German military doctor Hermann Frölich revisited Daremberg’s statistics,[4] refining and expanding them by analysing both the distribution and outcomes of wounds in relation to the weapons that inflicted them. More recently, authors such as Mirko Grmek, particularly in Diseases in the Ancient Greek World (1989), have contributed to the study of Homeric traumatology, comparing these data with more modern findings and engaging in detailed discussions of specific issues. However, these contributions have not substantially altered the conclusions initially formulated by Daremberg (1865) and Frölich (1879).

This evidence allows us to consider the possibility that the author of the Iliad, in addition to being a poet, may also have possessed knowledge akin to that of a military surgeon—or at least that of a priest with access to practical medical and anatomical knowledge accumulated over centuries. In this regard, Otto Körner (1929) argued that Book V of the Iliad, the Diomedeia, stands apart from the rest of the poem due to its strikingly advanced anatomical knowledge.[5] He further noted that this book exhibits a distinct morphosyntactic composition, which may reinforce the idea that it reflects anachronistic medical expertise.

Pharmacopoeia and Physicians in the Homeric World

Everything concerning the pharmacopoeia and the concepts of treatment, healing, and the administration of pharmakon in the Homeric world originates from the broader context of its Mediterranean habitat. It is possible to trace elements of this medical knowledge to earlier civilisations, such as Egypt,[6] before examining in detail the descriptions provided in the two poems. From the psycho-pharmacological traditions of Mediterranean cultures to alcoholic ferments, diet, and hygiene, particular emphasis is placed on wine, ambrosia, kykeon, and the foods mentioned in the Iliad and Odyssey.[7]

Luca Lippoli studied at the University of Bologna, graduating in “Anthropology and Oriental Civilizations” and in “Book and Document Sciences”. He is currently a professor of literature and history at the high school. Aspiring Candidate for a research doctorate, he is an active member of the CSMBR and holds the role of independent researcher of medical history and literature. He founded a bibliographic studio, where he deals with the sourcing, study and sale of ancient works from the medical world.

By means of direct textual comparison, the drugs and psychotropic substances of the Egyptian world can be analysed within the Homeric context, leading to an evaluation of the elements and defining characteristics of its pharmacopoeia.

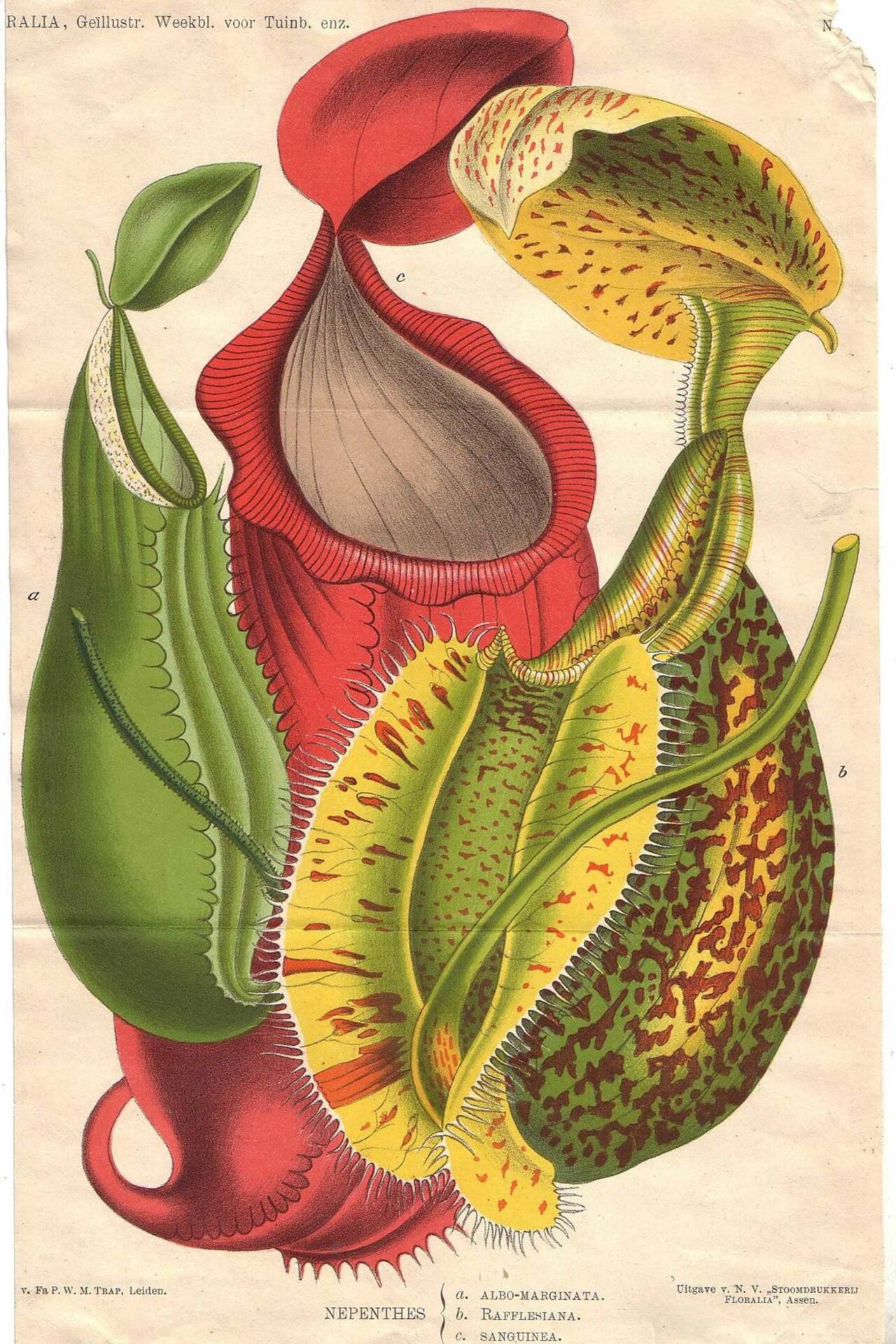

A primary role is given to narcotics such as opium, moly, and nepenthes, which carry both symbolic and ritualistic significance, closely linked to the conception of pharmakon in relation to magic and witchcraft [8] —although likely already distinct from medical knowledge. In the Iliad, there are numerous instances in which soothing ointments are applied to the wounds of heroes, serving as effective treatments. In this way, Homeric epic provides one of the earliest, if not the first, representations of a clear concept of drugs—not only among the Greeks but in world literature as a whole.[9]

The physicians mentioned in the Iliad are presented in a way that may seem bold but is not devoid of rigour and caution. Their primary attributes, their possible knowledge, and, above all, their high social status in the Homeric world are carefully outlined. The physician in the Iliad is a complex and multifaceted figure. The most prominent examples—though their roles are not overly emphasised—are Podalirius and Machaon, the sons of Asclepius. They are first mentioned in the Catalogue of Ships in Book II,[10] alongside other Greek leaders, for they, too, are kings and commanders who joined the Achaeans in their conquest of Troy.

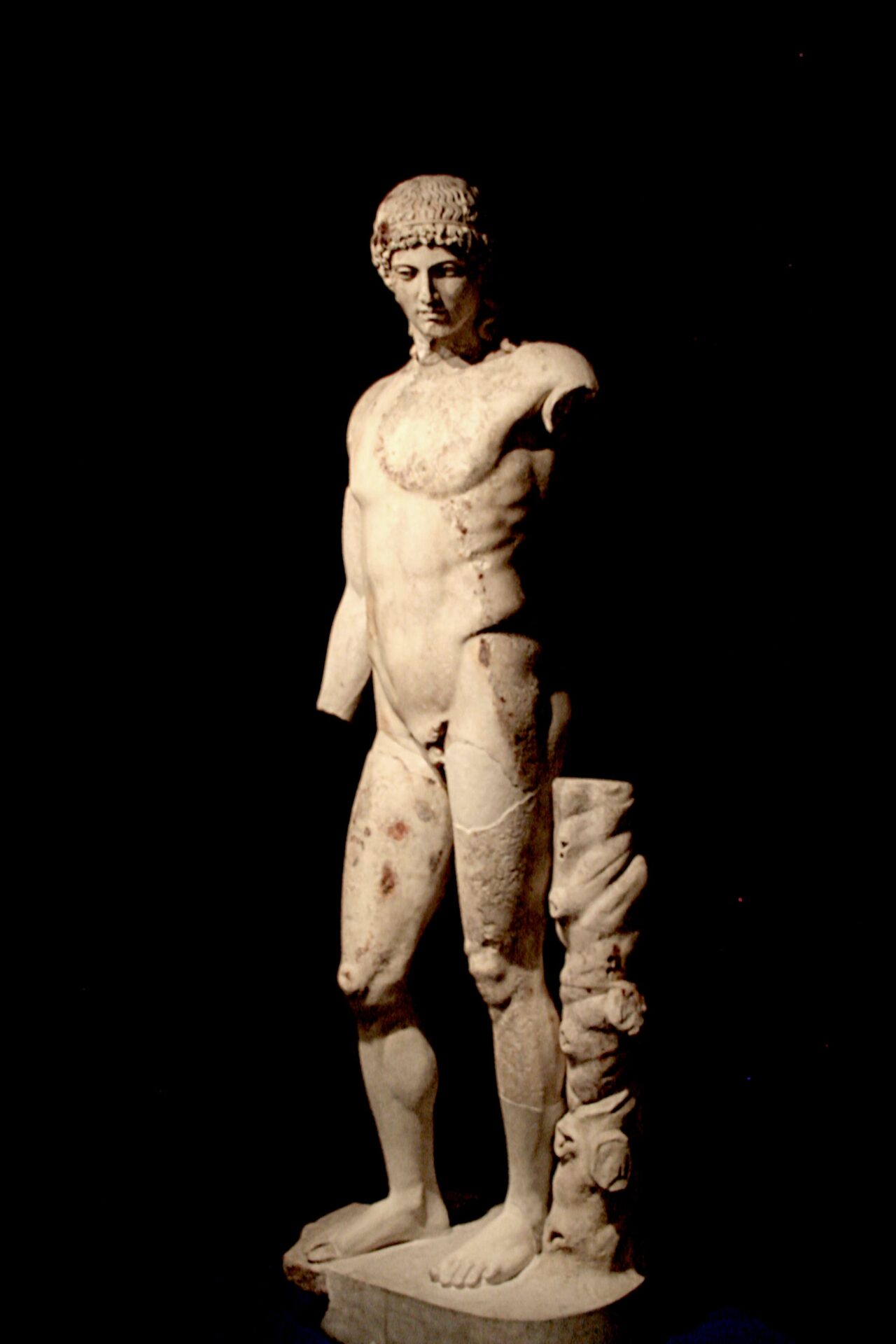

In archaic Greece, Asclepius was venerated as a medical hero, often associated with Apollo, the healing god, who was considered his father. The widespread belief that Asclepius was a full-fledged god, however, does not appear to have been firmly established before the fifth century BC, particularly in Epidaurus, from where his cult spread throughout the Greek world. Accordingly, his sons inherited his medical knowledge and, like him, were regarded as heroic figures. Their presence in the Iliad demonstrates the profound respect accorded to those who possessed medical expertise in archaic Greece. The fact that they are described as kings and commanders, leading thirty ships and fifteen hundred men (fifty per ship), serves as clear evidence of the high esteem in which the custodians of medical knowledge were held.

Among the two, Machaon, king of Tricca, receives greater attention. His significance becomes apparent in Book IV, when he is summoned by Agamemnon to treat Menelaus, who has been wounded.[11] Machaon intervenes with the confidence of a man who knows his craft. He promptly reaches Menelaus and removes the arrow, though the text indicates that some fragments remain embedded in the wound. With patience—though the precise technique is left unspecified—he manages to cleanse the wound and then, as is often described in the poem, applies soothing medicinal ointments. These remedies, we are told, were given to him by the Centaur Chiron, who had educated his father and was himself renowned for his expertise in the medical arts.

Figure 1. The so-called Tiber Apollo. Marble, Roman copy (2nd century CE) after a Greek original dated ca. 450 B.C. Inv. 608, National-Roman Museum, Palazzo Massimo Alle Terme, Rome.

Figure 2. Colored lithography of Nepenthe, from Pieter Willem Marinus Trap, Stoomdrukkerij Floralia (Assen: 1900).

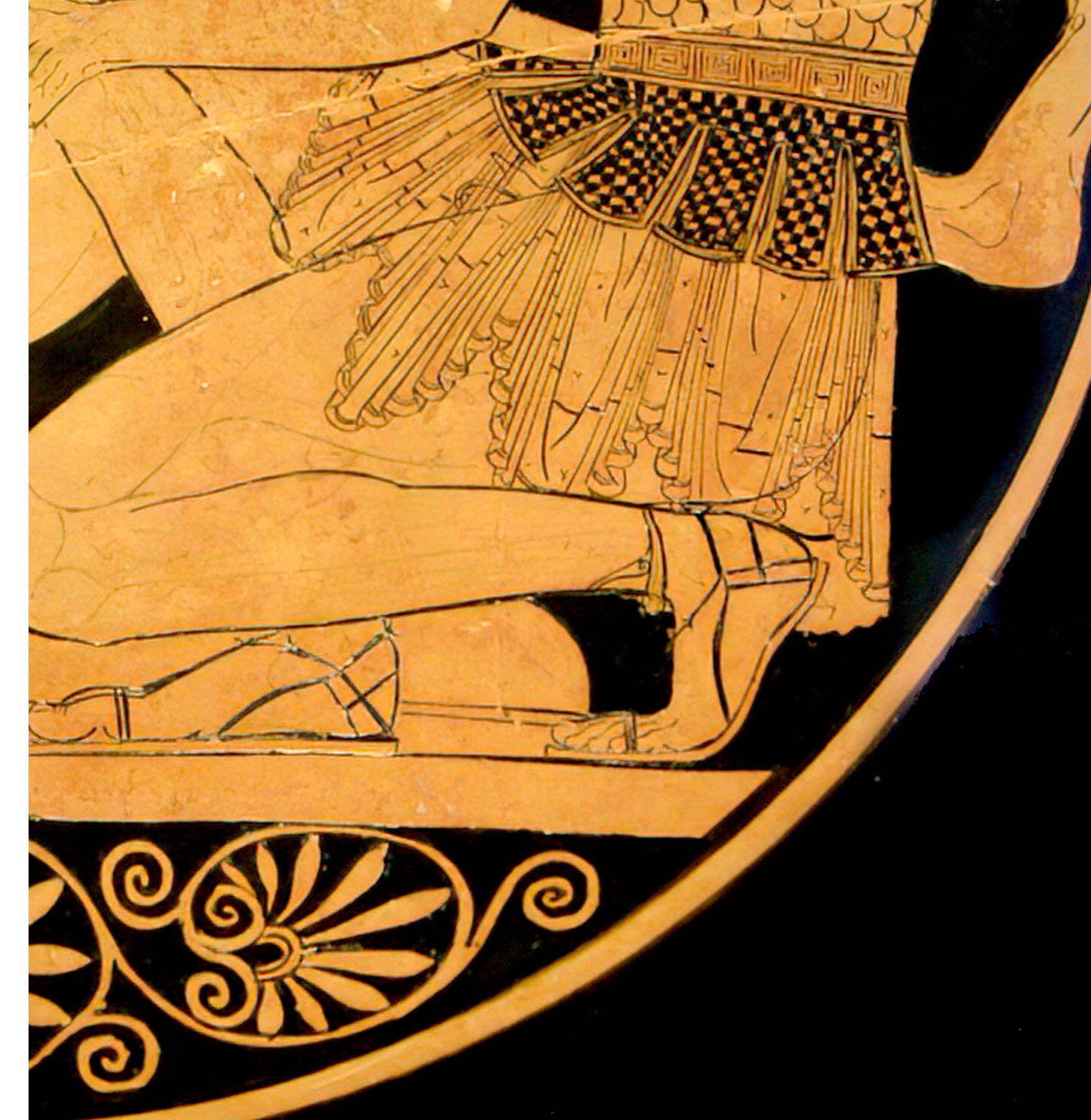

Figure 3. Top. Sosias, Achilles mend Patroclus. Ceramic, ca. 500 BCE – Altes Museum, Berlin (Nr. F 2278); Down. Surgical scenes from the Iliad and the Homeric Cycle from Charles Daremberg, “La médecine dans Homère” (Paris: 1865), VII.

In Book XI, Machaon is wounded by Paris, struck in the right shoulder with a three-headed arrow. His injury serves as a narrative catalyst: the Achaeans are gripped with fear, sensing ominous signs, as if the outcome of the war might depend on his fate. This moment further reinforces the idea that physicians in the Iliad are held in the highest regard, verging on divine reverence. Idomeneus is the first to come to Machaon’s aid, urging Nestor to take him to the ships, emphasising that he is not merely an aristocrat but a physician, worth more than a thousand men.[12] As further proof of the respect he commands, Achilles—on the verge of rejoining the battle—also expresses concern for the physician’s condition. So much so that he sends Patroclus himself to check on Machaon in the Achaean camp. [13]