Medical Electricity Arrives in Italy

FORMA FLUENS

Histories of the Microcosm

Medical Electricity

Arrives in Italy

Eighteenth-Century Interactions

between Electricity and the Body

Lorenzo Voltolina

University of Padua

From Amber to Electrical Therapies

During the first half of the Eighteenth Century, electricity evolved from a peculiar natural curiosity – an occult attractive property manifested by rubbed pieces of amber – into a fully fledged field of scientific research. From a material-culture perspective, this transformation was largely driven by the diffusion of mechanically rotated tribo-electrical machines, inspired by Francis Hauksbee’s early-century design employing an evacuated glass globe [Figure 1], and by the discovery of the Leyden jar, the first electrical condenser. These devices soon enabled the observation of new effects, such as “rains of lights” in rarefied air and the transmission of electrical virtues over considerable distances and across multiple bodies. Accordingly, the magnitude of electrical phenomena increased drastically: shocks became stronger, clearly perceptible, and (as we can now imagine) even painful. [1]

At the same time, the human body became an integral and essential component of electrical demonstrations. Beginning with Stephen Gray’s Flying Boy experiment of the 1730s, in which a 47-pound Charterhouse charity child was suspended from the ceiling by silk threads (thus, isolated) and then electrified, and would hence acquire attractive virtues, the body emerged as both an experimental object and a demonstrative medium [Figure 2]. Almost immediately, reports concerning the physiological effects of electricity began to circulate. For instance, George Matthias Bose’s early-1740s experiments on the influence of electricity on plant growth, his capacity to kill small animals through shocks, and his spectacular public demonstrations (most famously the Beatification and the Venus Electrificata) resonated widely across Europe. The modes of interaction between living bodies and electricity rapidly became a central topic of discussion. [2]

Shortly thereafter, from 1745 onwards, research into the supposed healing virtues of electricity attracted particular attention, especially through the work of Johann Gottlob Krüger and his pupil Christian Kratzenstein. Building on the observation that electrification produced muscular contractions, they reportedly treated various forms of paralysis by “extracting sparks” from the affected body parts, intending to regenerate and invigorate them. Sparks, shocks, and electrical therapies thus formally entered medico-physiological discourse, contributing to the diffusion and growing popularity of this new body of theoretical and practical knowledge that combined physics with medicine. [3]

Italy witnessed several, rather peculiar, episodes related to the rise of medical electricity, two of which received particular attention in recent historiography. The first is the internationally resonant controversy surrounding the efficacy of the so-called tubi medicati: glass tubes, allegedly invented by Gianfrancesco Pivati in 1747, internally coated with healing balsams or oils which, after electrification, were claimed to transmit healing virtues from the inside of the tube, through the glass, into the patient’s organism. The second episode took place in Vicenza, also in 1747, and concerned Marquise Luigi Sale’s cure of a sleepwalker through electrification sessions. [3] [4]

By contrast, an earlier episode has attracted far less scholarly attention: the publication of the first Italian treatise devoted entirely to electrical science, Dell’Elettricismo (1746), and its explicit discussions of electricity’s possible application within the medical realm. Notably, the medical content of this work – of which a preliminary overview and analysis are offered here – has never been studied in detail by historians. [2] [3] [4] [5]

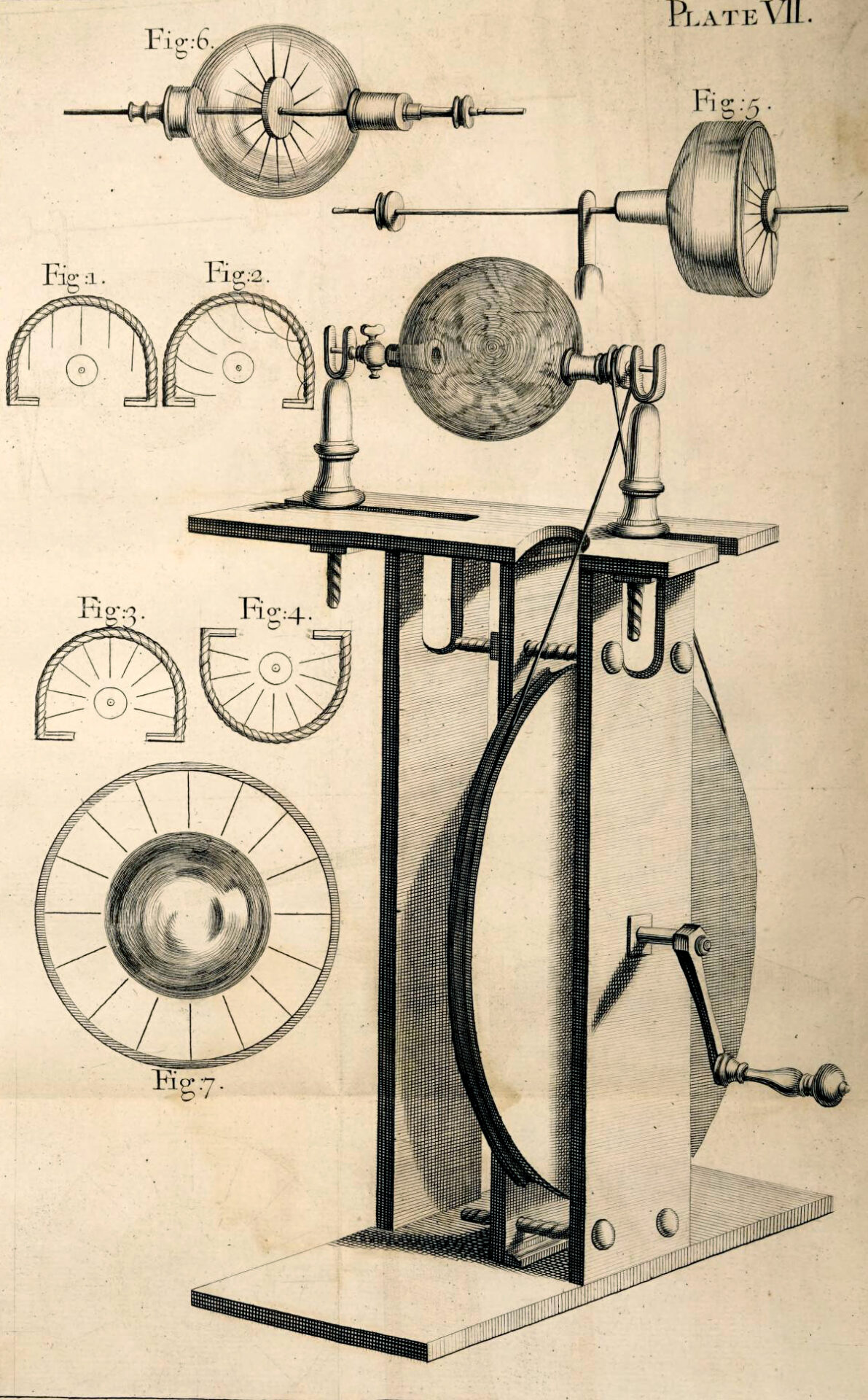

Figure 1. A depiction of Francis Hauksbee’s triboelectric machine, composed of a glass globe (that could be emptied to create a vacuum inside it) and a big cranked wooden wheel used to spin it: a design that would remain almost identical until the Nineteenth century. The etching also depicts some experiments performed with it on the attraction of light bodies, such as small threads; from Francis Hauksbee, Physico-mechanical Experiments on Various Subjects (Brugis: London, 1709).

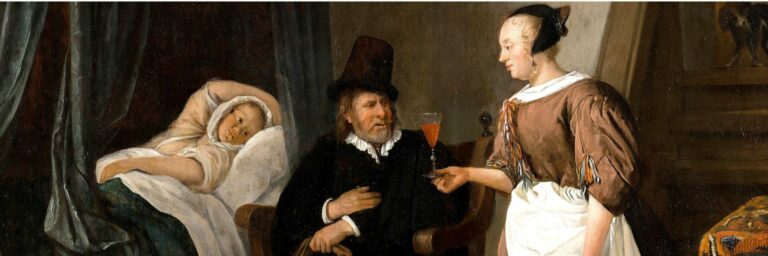

Figure 2. The “flying girl”. Opening illustration of Dell’Elettricismo (Recurti: Venice, 1746). The etching depicts a “salon version” of Gray’s Flying Boy experiment, where a young girl, suspended by silk threads, ignites an alcoholic spirit with the touch of a finger after being connected to an electrical machine.

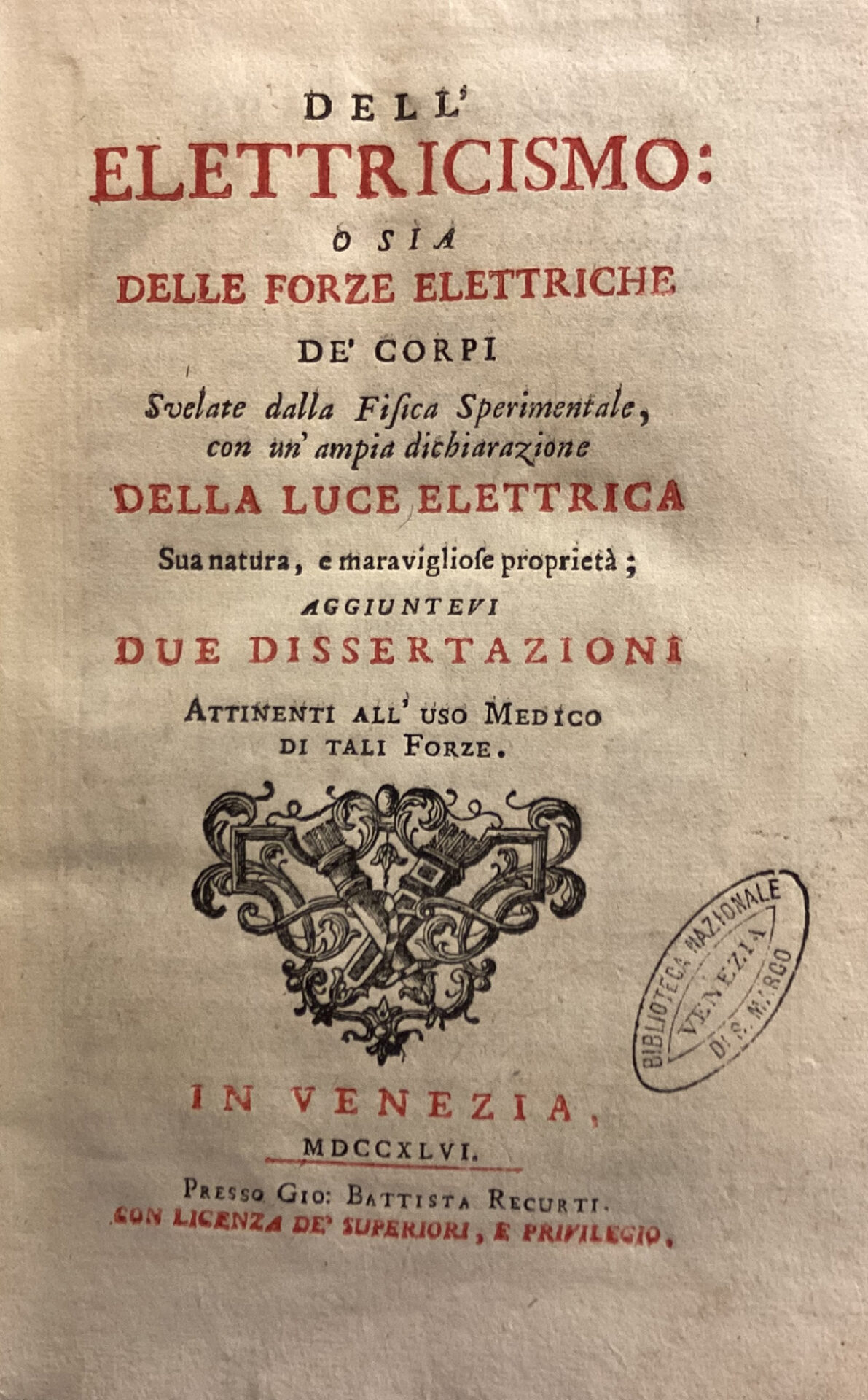

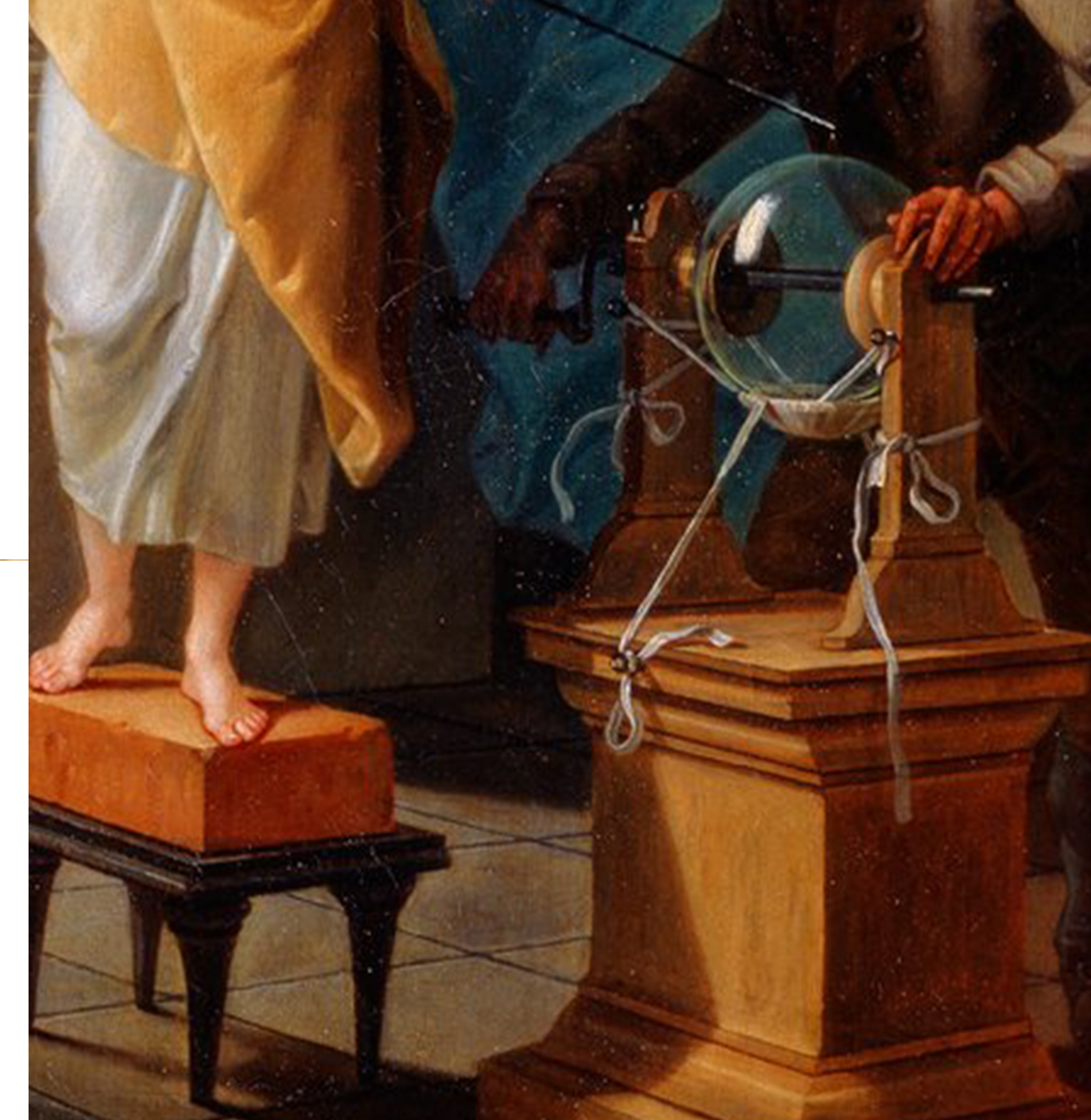

Figure 3. Frontispiece of Dell’Elettricismo (Recurti: Venice, 1746).

First Sparks of an Interdisciplinary Knowledge: "Dell’Elettricismo" (1746)

Dell’Elettricismo, o sia delle forze elettriche de’ corpi svelate dalla fisica Sperimentale, con un’ampia dichiarazione della luce elettrica, sua natura e meravigliose proprietà: aggiuntevi due dissertazioni attinenti all’uso medico di tali forze (“On Electricity, or the Electrical Forces of Bodies Revealed by Experimental Physics, with an Extensive Explanation of Electrical Light, its Nature and Marvellous Properties; with Two Dissertations Added Concerning the Medical Use of Such Forces”) is the first Italian treatise entirely devoted to electricity [Figure 3]. Published in Venice in 1746, it quickly became a bestseller, circulating widely throughout Europe, with a Neapolitan reprint following immediately after the Venetian edition. The work stands as a comprehensive and up-to-date compendium of all the then-known experiments, instruments, devices, and theories concerning electricity, while also introducing several noteworthy innovations, such as an early measurement device for electrical charge, the elettrimetro, and one of the earliest explicit correlations between electricity and lighting. [6] Admired by leading figures of the period, including the abbé Jean-Antoine Nollet, the foremost electrical experimenter of the time, the book functioned as an important medium for the diffusion of electrical knowledge. [5]

One of the most striking features of Dell’Elettricismo is its anonymous publication: indeed, its authorship remains an open question for historians. [3] [4] [5] Two names are usually associated with the work: the Venetian Eusebio Sguario, a practicing doctor and well-known figure within the Northern Italian intellectual milieu, and Christian Xavier Wabst, a Saxon physician serving the Austro-Hungarian army and stationed in Venice. At the time of the book’s publication, both were actively engaged in offering electrical divertissements in Venetian aristocratic salons – Sguario charging 20 soldi per session, Wabst 24. [3] It is therefore already noteworthy that the first Italian treatise on the nature and properties of electricity was almost certainly authored by doctors. Reflecting this medical expertise, Dell’Elettricismo contains an entire section devoted to the possible healing powers of electrical therapies – the “due dissertazioni” mentioned in the book’s title.

These two final texts, however, should not be regarded as marginal addenda. Rather, they constitute a conceptual bridge between experimental natural philosophy and the medical realm. Read together, they enact a two-step argumentative operation. The first dissertation, Delle forze elettriche ad uso della Medicina Teorica, con una breve Spiegazione dell’origine della materia sottile che le rappresenta, addresses key physiological questions on the interaction between electricity and bodily fluids. In doing so, it also proposes a new interpretation of what the “subtle electrical matter” ought to be, drawing on a broadly Newtonian framework while still referring to a universal Cartesian aether. The result is a general yet very fascinating comparison between electricity, vital forces, and animal spirits. The second dissertation, Delle forze elettriche ad uso della Medicina Pratica, on the other hand, is grounded on the theoretical premises of the previous text, then adopting a much more markedly experimental approach. First, it describes the phenomenology of electrical sensations experienced by different parts of the body, and then it presents a series of experiments aimed at inquiring whether (and in what manner, and to what extent) it may be legitimate to include electricity in therapeutic practices for specific diseases. [6]

Electrifying the Blood

Among the various themes addressed in the two dissertations, the relationship between electrical subtle matter and blood occupies a structurally unifying position. The opening question of the first dissertation is whether blood, by virtue of the friction generated by its continuous motion within the vascular system, could naturally acquire electrical properties, and whether such properties might contribute to an explanation of the inner nature of bodily heat, thus engaging explicitly with the theories advanced by Stephen Hales.

Lorenzo Voltolina is a PhD student in the History of Physics at the University of Padua. His research focuses on 18th-century electrical science, particularly the work of Giovanni Poleni, exploring his unpublished writings and extensive international correspondence. He holds B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees in Physics, as well as an M.Sc. in the History and Philosophy of Science. In the past decade, he worked as a mathematics and physics teacher in secondary education schools across the Venetian Lagoon region, setting up interdisciplinary projects that bridge science, history, philosophy, literature, and art.

The author of Dell’Elettricismo investigates this hypothesis through careful observations. If blood were intrinsically electrical in vivo, it should retain detectable electrical properties when extracted from the body while still warm. Yet, experiments conducted with fresh animal blood contained in thin glass vessels consistently failed to produce attraction of light bodies or other characteristic signs of electrification. On this basis, the author explicitly rejects the idea that the circulation of blood alone can generate sufficient electrical matter to account for vital heat.

Rather than abandoning the problem, however, the dissertation reframes it. Drawing on previous analysis of the heterogeneous composition of blood, the author emphasizes that its largest portion, estimated in a 13:16 ratio, consists of aqueous and serous components, whereas the “sulphureous” fraction, associated with combustibility and electrical responsiveness, constitutes only a minor part, in a 1:23 ratio. From this perspective, the failure to detect blood’s electrical properties directly becomes intelligible: blood is not an “originally electrizable” substance like glass or resin; nevertheless, this does not exclude a role in electrical processes. On the contrary, blood is reinterpreted as a vehicle and moderator of a subtler, more universal matter. This conceptual shift underpins the dissertation’s central theoretical claim: the identification of vital heat with electrical matter in a state of intense agitation. Blood, then, does not generate electricity through friction, but circulates within a body permeated by an electrical ether that is responsible for warmth, sensibility, and the activity of the “vital spirits.”

The second dissertation shifts focus toward practices and experiments, examining the relationship between blood and electricity from a different angle: not ontological, but physiological and therapeutic. Here, the central question becomes whether the electrification can measurably alter the blood’s motion, and whether such alterations might bear some usefulness in therapeutic contexts. A research question thus naturally arises from the conclusions of the first dissertation: blood is not inherently electric; nonetheless, can it be electrified and successfully retain electrical properties?

This question culminates in one of the most distinctive and innovative experiments described in the treatise: the electrification of the body during bloodletting. The experimental setup closely mirrors the illustration that opens the book, depicting a slightly modified version of Gray’s Flying Boy experiment. A young person is suspended from the ceiling by silk cords, then connected to a functioning electrical machine and thereby, in modern terminology, charged by friction. The author then describes the bloodletting procedure itself: a vein of the isolated subject is cut, and the flowing blood is collected into a metal basin placed over a wax cake, thus ensuring its electrical isolation too. The first observational result is an increase in both the velocity and abundance of the blood flow. On the other hand, the undisputable and decisive evidence of blood being electrified lies in the luminous and crackling sparks emitted at the point of contact between the bloodstream and the basin. To determine whether blood can retain electrical properties, the vein is closed and reopened several times in succession. The author notes that the number and magnitude of the sparks remain nearly constant across these subsequent trials, suggesting that the electrical “virtue” is not dissipated immediately into the surrounding environment.

The epistemic significance of the bloodletting experiment is crucial. Bloodletting was among the most standardized and widely practiced medical procedures of the period, and precisely for that reason, it provided a stable and familiar observational framework. By introducing electricity into this well-established clinical setting, the author was able to compare its effects directly with those of conventional medical manipulations.

Across both dissertations, then, blood serves as a conceptual hinge. In the first, it anchors a critique of simplistic mechanical models of vital heat, while enabling a more sophisticated electrical physiology; in the second, it provides a measurable index of electricity’s action on the living body.

Finally, within the section of Dell’Elettricismo devoted to medical electricity, another crucial experiment addresses the effects of electricity on blood circulation. While it was already well established that electrification causes an acceleration of the pulse rate, attempts to quantify this acceleration remained controversial. The author directly challenges Kratzenstein’s claim to have identified a general mathematical law describing this effect (a standardized increase of roughly 10%) by showing that such a generality is, in fact, contradicted by his own experiments. Nonetheless, the observed acceleration is interpreted as evidence that electricity can indeed “put the blood into a brisker motion.” Crucially, however, the author immediately relativizes this finding: walking, running, and other forms of physical exercise produce similar effects. An increase in pulse rate, therefore, cannot be regarded as a specific therapeutic signature of electricity, but rather a general physiological response to stimulation. Moreover, since electricity demonstrably affects blood motion, it must be used with caution: the author explicitly warns against electrifying patients who have recently suffered hemorrhages or are prone to spitting blood. Conversely, the same circulatory stimulation may explain why some subjects reported sensations of lightness, warmth, and improved mood after electrification sessions. [6]

Epistemological Remarks: Medical Authority and Experimentation

As a concluding remark, it is worth briefly pausing on the epistemological stance that permeates the entire section on medical electricity and offers valuable insight into how this emerging science could be understood by practicing physicians of the period. The quotation opening the section, by Robert Boyle, clearly conveys a cautious and skeptical attitude, likely directed against the exaggerated claims of electrical healers who persisted in defending the results obtained, even in the face of unsuccessful trials:

It should be considered less indecent to renounce error for the sake of truth than to petulantly and pompously support an opinion merely because one once believed it true.

This position is consistently reinforced throughout the text, which repeatedly stresses that medical utility can be established only through “authentic facts.” Until such evidence is produced, electricity is to be “irremediably sent back to Experimental Physics, to which it rightfully belongs”. In this way, the author simultaneously acknowledges the inflated social enthusiasm surrounding electricity and delineates a disciplinary boundary that only rigorous experimentation could eventually overcome.

In his criticism, the author is most likely once again targeting Kratzenstein, this time for his reported cures of paralyzed fingers, first in a young woman and subsequently in an older man who allegedly regained the ability to play the harpsichord. The author of Dell’Elettricismo, however, dismisses these cases as involving “mild and recent afflictions”, rather than constituting genuine demonstrations of electrical healing of a permanent condition. In doing so, he reasserts a demand for methodological rigor and long-term observation, thereby situating medical electricity not as a realm of marvels and immediate cures, but as a provisional and carefully circumscribed extension of experimental physics into the medical domain. [6]

Conclusions

This article has examined Dell’Elettricismo as an early and largely overlooked site of interaction between experimental physics and medicine in mid-eighteenth-century Italy. Rather than treating medical electricity as a marginal curiosity or as a collection of anecdotal cures, the treatise advances a structured attempt to integrate electrical phenomena into physiological reasoning and therapeutic practice, while simultaneously delineating the epistemic boundaries of legitimate medical knowledge. The two final dissertations articulate a progression from speculation to controlled experimentation, in which the human body functions as a privileged mediator.

By analyzing experiments on blood electrification, circulation, and pulse acceleration, Dell’Elettricismo demonstrates both an openness to the medical potential of electricity and a marked resistance to premature generalization. Ultimately, Dell’Elettricismo presents medical electricity not as a revolutionary cure-all, but as a provisional extension of experimental physics into the medical domain, whose legitimacy depends on repetition, quantification, and long-term observation. In doing so, it offers a new perspective on how Italian practitioners navigated novelty, authority, and interdisciplinarity during a formative moment in the history of science.