Ole Borch on Indigenous Plants

FORMA FLUENS

Histories of the Microcosm

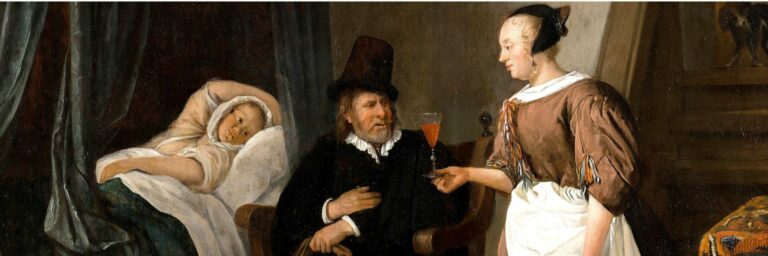

A Witness to 17th-Century Medical Practice

Ole Borch and the Medical Use of Indigenous Plants

Doriane Moenaert

Université Catholique de Louvain

Comèl Grant

In 1690 a treatise entitled De usu plantarum indigenarum in medicina was published in Copenhagen. Its author was Ole Borch (1626-1690), a professor of botany, chemistry and medicine at the University of Copenhagen. In the introduction—dated 15 November 1686—Borch makes it clear that the aim of the work is to present indigenous plants that could be used to treat diseases. This article offers an analysis of the introduction to De usu plantarum and shows how Borch, as a witness to developing botanical knowledge and trends, made a significant contribution to seventeenth-century medicine.

As I have demonstrated in my study of his treatise Dissertatio de causis diversitatis linguarum,[1] Borch was a true polyhistor, well-versed in ancient sources as well as the works of his predecessors and contemporaries. His expertise encompassed both theoretical and practical foundations. A brief biographical outline will illustrate this claim.

Borch’s Biographical Outline

Ole Borch, or Olaus Borrichius by his Latin name, was born on April 7, 1626, in Borchen, Denmark. The son of a pastor, he began his studies at the University of Copenhagen in 1644, focusing on medicine, literature, poetry, and philosophy. His first dissertation dealt with the Kabbalah. After working as a Latin teacher and tutor to Joachim Gerstorff’s children, he gained recognition as a physician during the 1654 plague epidemic. Appointed professor at the University of Copenhagen, he undertook responsibilities in philology, chemistry, and botany. His appointment included permission to embark on a six-year “educational journey” across Europe, during which he met scholars from diverse fields and kept a detailed travel diary. Upon returning, he resumed his academic duties and served as physician to the king. His writings reflect his broad interests, encompassing chemistry, alchemy, botany, and philology. Borch died without heirs, leaving his wealth to his students and to the college he established in Copenhagen, Borchs Kollegium, which still exists today. [2] This biographical account illustrates Borch’s theoretical and practical knowledge, as well as his role in the intellectual practices of his time. An analysis of the introduction to De usu plantarum indigenarum in medicina will provide further insight. [3]

The Introduction to De usu plantarum indigenarum in medicina

Borch begins his book by dedicating it to the flourishing youth of the Copenhagen Academy, as well as to all those born for the salvation of mankind. He later clarifies that this refers to students of medicine but extends more broadly to anyone wishing to care for themselves, friends, or the destitute, motivated by sincere charity (sincerae charitatis). Too many, he argues, have died not due to a lack of curative plants but because of the ignorance of those around them. The geographical focus of the treatise includes the land of the Cimbri, Norway, and Iceland. Borch emphasises that the earth is generous everywhere, which explains his decision to exclude exotic plants from this work—although he covers them in his courses. While effective, such plants are often more expensive and less accessible. Since the true beneficiaries of his treatise are the destitute, Borch felt compelled to justify his choice of Latin over Danish; this will be revisited later in the discussion. Another important point in his introduction is Borch’s opposition to pure botanists who catalogue plants individually with their medicinal effects. Instead, he prioritises effective treatment, reversing the usual approach: for each disease, he explains which plants can cure it. Furthermore, he criticises botanists for their poor understanding of medicine, noting that they often recommend harmful plants (adeo non tollent illae morbum ut tollant potius aegrum). Using two common examples, Borch demonstrates his competence and extensive experience (propriis tot annorum experimentis), completing his justification for the treatise’s utility.

I will now revisit the key points identified in this introduction to explore general trends in seventeenth-century medicine and Borch’s originality

Recipients and Aim

De usu plantarum indigenarum in medicina is intended for clergy and physicians tasked with the charitable work of disseminating essential medical knowledge throughout the Nordic countries. While it might seem unusual for pastors or religious figures to study medicine, Danish clergymen were expected to have basic medical knowledge to emulate Jesus’s healing.[4] Furthermore, from the sixteenth century onwards, European states began implementing official measures to provide healthcare systems for the destitute.[5] The Christian religion has historically had an ambivalent relationship with “secular” medicine. Some Christians opposed Galenic medicine, believing that true faith negated the need for it, while others viewed it as complementary to Christ’s healing.[6] The epidemics that ravaged Europe necessitated combining pious prayers with practical medical care.[7] As a deeply religious man, Borch likely intended this treatise to integrate his medical practice into the framework of Christian charity. For the same reason, he does not dwell on ancient authors, noting that many of his readers aspire more to divine oracles than to those of Hippocrates, Theophrastus, or Dioscorides.

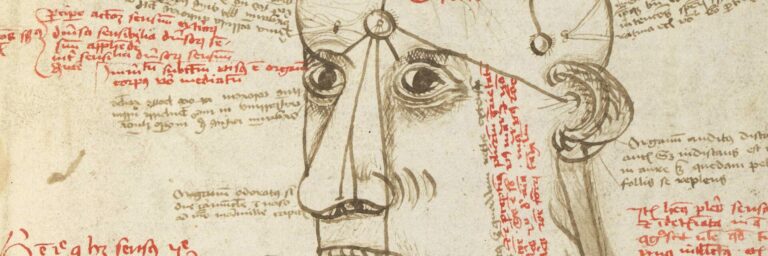

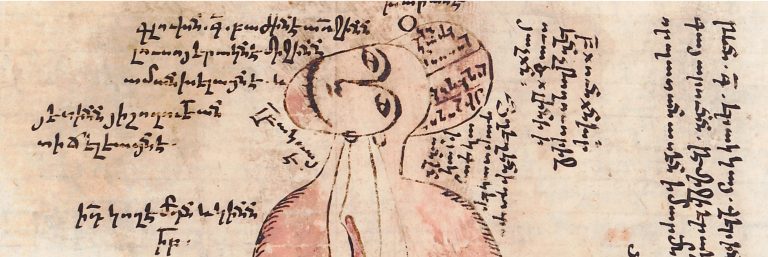

This requires some context on seventeenth-century medical knowledge. Until the sixteenth century, Galenic medicine had dominated Europe. However, with the rediscovery of Greek texts during the Renaissance, a more Hippocratic approach began to take precedence. Paracelsus’s iatrochemistry also gained influence across Europe from the sixteenth century onwards.[8] Borch was well-versed in the “oracles” (oracula) of ancient authors—as he puts it—but prioritised practicality.[9] Professors of medicine in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries typically held degrees in arts, ensuring their proficiency in classical languages and enabling them to translate required texts without waiting for philological editions.[10] The aim of Borch’s work is not botanical classification but practical application. He seeks to equip readers to treat the poor at minimal cost by providing simple, useful, and enduring knowledge. This act of Christian charity eschews purely botanical or exotic digressions, which Borch addresses separately in his academic lectures. His treatise serves as a compendium of accessible medical knowledge, intended to be shared widely, especially in less privileged regions.

Indigenous Plants and Language

While Borch’s focus on indigenous flora is clear from the title, he justifies his use of Latin rather than Danish in his introduction. He recognises that Danish would have been more suited to his purpose, but chose Latin to ensure uniformity of plant nomenclature, citing the confusion caused by the different Danish dialects. Earlier authors had similarly focused on local flora to promote accessible remedies for the poor, often writing in vernacular languages to break with learned traditions.[11] Borch, however, saw Latin as a means to bridge accessibility and uniformity, especially when combined with visual identification of plants during treatment.

In the sixteenth century, debates over pharmacy reflected a tension between the rediscovery of ancient texts, such as those by Dioscorides and Avicenna, and a reaction favouring local flora over exotic imports.[12]

Doriane Moenaert is a Doctoral Candidate and Assistant Professor, focusing on Latin Alchemy from the 12th to the 14th centuries. She studied Classical Philology at Louvain-la-Neuve and at the University of Bologna, where she also conducted research on 17th-century medicine. Since September 2019, she has been engaged in her doctoral thesis under the supervision of Dr. Sébastien Moureau.

Advocates for the latter argued that local plants were divinely suited to the needs of local populations and offered remedies accessible to the poor. [13] Borch’s work follows this tradition, aiming to equip students, physicians, and clergy with tools to treat the destitute using free, local plants rather than expensive imports from India or Americas, reserved for the elite.[14]

Format and Practice

Borch’s purpose shapes the format of his work, presenting remedies by disease to prioritise practicality over botanical exhaustiveness. This approach allows physicians to quickly identify treatments without sifting through an extensive herbarium. His treatise excludes theoretical considerations, reserving them for his courses. This aligns with the medical teaching of his time, which relied on vade-mecum or practica—manuals listing diseases and treatments—combined with practical instruction such as anatomy lessons, botanical garden visits, [15] or patient care under a professor’s guidance.[16] A depiction of Borch shows him teaching in the garden with his students [Fig. 1].

Figure 1. Ole Borch on a botanical excursion with his students around 1680; from Itinerarium Oligeri Jacobæi, MS Ny kgl. Saml.375, 4o, p. 68. Arhaus, Denmark.

During the Renaissance, a new form of practical medical writing, the observationes, emerged alongside the medieval practica and vade-mecum. These compilations of case histories, based on the author’s experiences or observations, gained popularity and eventually became the dominant form of medical writing by the eighteenth century. There was also a growing preference for light, portable works, which Borch embraced, describing his own treatise as light and not cumbersome.[17] Like many physicians of his time, Borch combined academic training at major European universities with practical experience in smaller communities. [18] His work reflects this dual perspective, offering a concise, practice-oriented text based on his own experiences. As I noted earlier, Borch criticises botanists without medical training and supports his claims with examples from his practice. Although a botanist himself, Borch’s medical experience aligns him with contemporaries who sought to teach by drawing from nature itself and their own personal expertise.

In short, Borch fought against botanists who claimed to heal without medical knowledge and who did more harm than good. He argues that his personal experience is sufficient to write this compendium, and he intends to make this compendium a small table summarising “the great territory of medicine, which must be grasped at a glance for the relief of the sick and especially the poor”[19], again emphasising the practical and effective nature of his work. All these observations tend to explain every detail of Borch’s introduction:

-

-

- Like many others, he makes his work practical;

- He intends it for students and clergy who will perform acts of charity;

- He restricts his claims to native plants;

- He restricts the geographical area to which his work applies, unlike Galen who thought he could treat the whole empire;

- He explains his choice of Latin because it might be criticized;

- He mentions that his work is a small thing by its weight;

- He accuses botanists who are not practitioners of aggravating disease while claiming to cure it.

-

In conclusion, Borch can rightfully be considered a witness to the medical practices of his time, while also showcasing originality in certain respects. His innovations are most apparent in his proposed treatments rather than the format of his work. While his methods, vision of disease, and the materials he used draw from tradition, his specific responses reflect his personal experience and practice as a physician.

Like many contemporaries, Borch prioritises practice as a source of new knowledge. He provides limited dosage information in his text, likely because these details were covered in his courses or tailored to individual practitioners. He distances himself from Theophrastus and Dioscorides, arguing that modern Christian medicine should not depend on plants from distant Mediterranean regions. Though well-versed in these classical sources, his practice enabled him to develop independent views on local plants.

The format of Borch’s work aligns with the growing trend of seventeenth-century medical texts that report first-hand clinical observations. These texts emphasised light, portable formats with specific, practical goals, such as focusing on indigenous plants while maintaining the ambitious aim of treating the poor.[20]

Borch’s significance lies in his ability to navigate the tensions of his era: balancing ancient and modern medicine, Latin and vernacular languages, theoretical and practical knowledge, and religious and secular healing. His practical manual in Latin, centred on local plants and organised by disease, reflects a thoughtful synthesis of these competing demands. While rooted in tradition, his therapeutic recommendations are grounded in his extensive personal and local experience, offering valuable insights into how practitioners adapted medical knowledge to local needs while engaging with broader European developments in medicine and education.