Follow your Heart but Heed your Brain

FORMA FLUENS

Histories of the Microcosm

Follow Your Heart

but Heed Your Brain

Pietro Pomponazzi and the Renaissance Debate on Sense Perception

Leonardo Graciotti

University of Genua

Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne

One of the most heated debates in the Latin West’s medical-philosophical tradition, from the rediscovery of Aristotle’s libri naturales through the Renaissance and beyond, concerns whether cognitive functions are governed by the heart or the brain. According to Aristotle, the heart is the primary organ of the animal body: it is the source of heat and life, as well as the seat of the “common sense” and voluntary motion. In contrast, drawing on Hippocratic physiology and Platonic tripartite psychology, Galen identifies three main organs responsible for bodily functions: the liver, the heart, and the brain—with the latter controlling voluntary motion and sensation through the nerves and spinal cord.

The differences between the master of philosophers and the prince of the physicians undermined the age-old alliance of philosophy and medicine, prompting early Arabic authors (e.g., Avicenna and Averroes) and later Latin authors (e.g., Pietro d’Abano) to seek conciliatory solutions. This article focuses on the specific issue of the location of the sensitive faculty as discussed by one of the most prominent Aristotelian philosophers of the Italian Renaissance, namely Pietro Pomponazzi (1462 – 1525). During one of his courses on De anima, held in Bologna around 1514-1515, Pomponazzi questioned whether the common sense should be located in the brain or in the heart (Utrum sensus communis sit in cerebro vel in corde). He regarded this topic as highly relevant, despite it often being overlooked by the masters of natural philosophy, as it pertains two lesser studied works from the Aristotelian corpus: De partibus animalium and De sensu et sensato.[1]

Pomponazzi explains that Aristotle considered the common sense as the bodily function (virtus corporalis, virtus organica) responsible for sense perception, and placed it in the heart, which is the source of blood (principium sanguinis) as well as the principle of life and nourishment (principium nutrimenti et vitae). Since the animal’s existence relies on its sensitive faculty—without which one could not recognise what is beneficial from what is harmful—it is evident that the principle of sensation is to be found where the principle of life is located. Moreover, the heart is composed of a mixture of flesh and nerves, making it perfectly suited for sensitive perception (substantia apta ad sensationem), unlike other non-sensitive organs such as the brain.[2]

By contrast, Plato, Galen, and the physicians believed the brain to be the source of sense perception (principium sensus) because the nerves that transmit sensory information originate there and are significantly larger (nervi valde magni) than those found in the heart. They also argued that the blood in the brain is finer and more refined, making it better suited for sense perception compared to the hot and coarse blood present in the heart.[3]

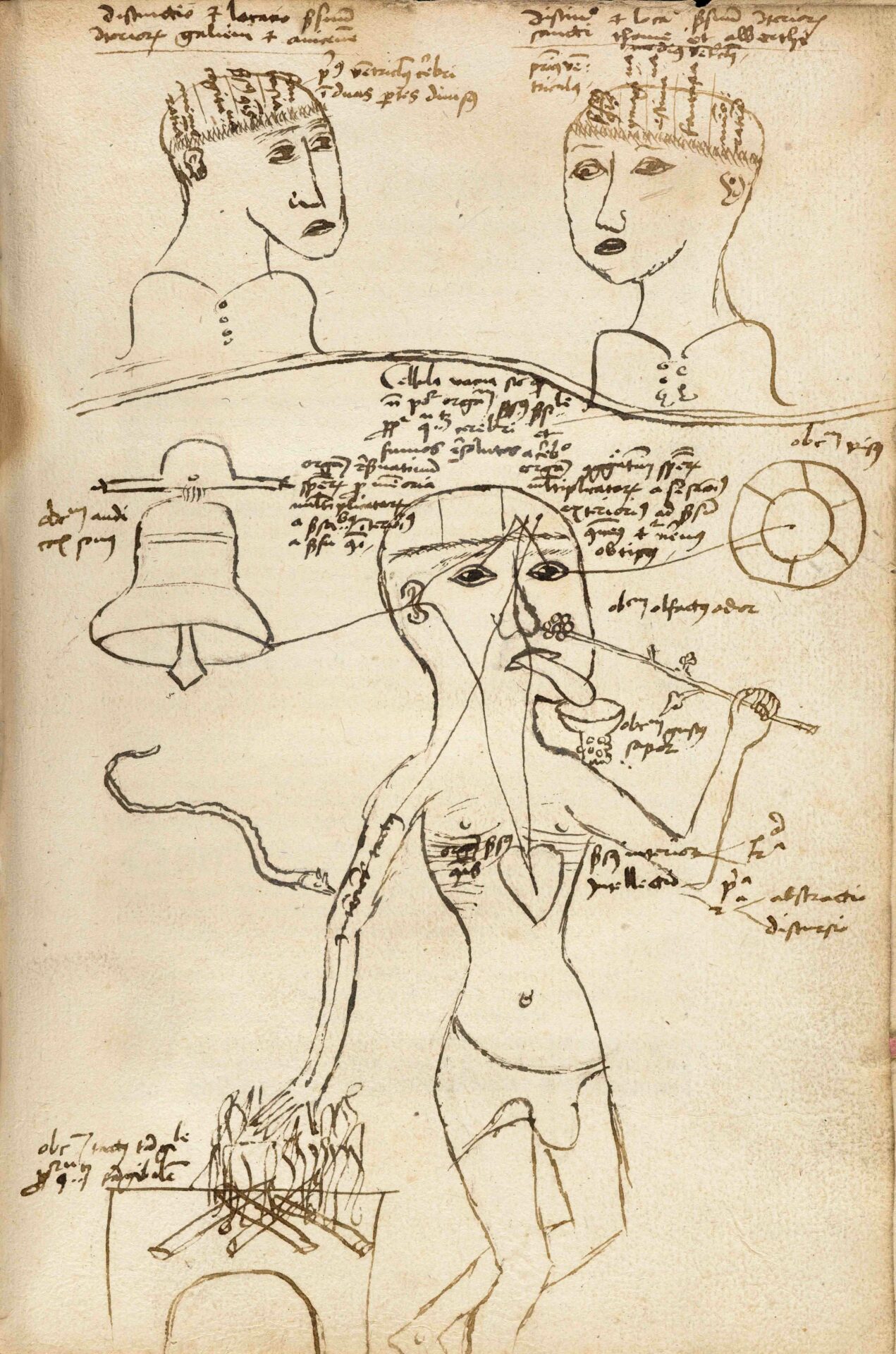

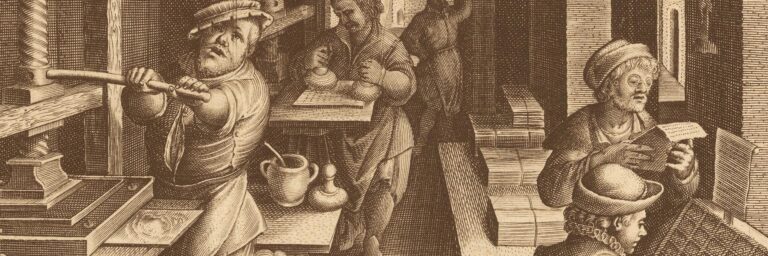

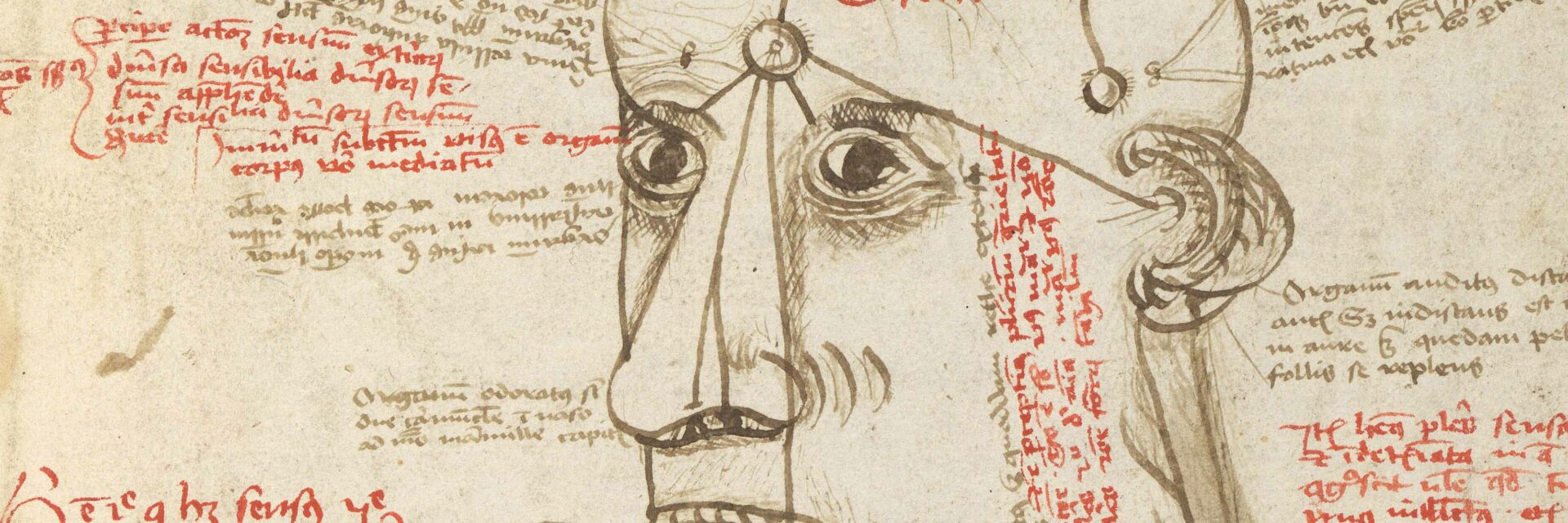

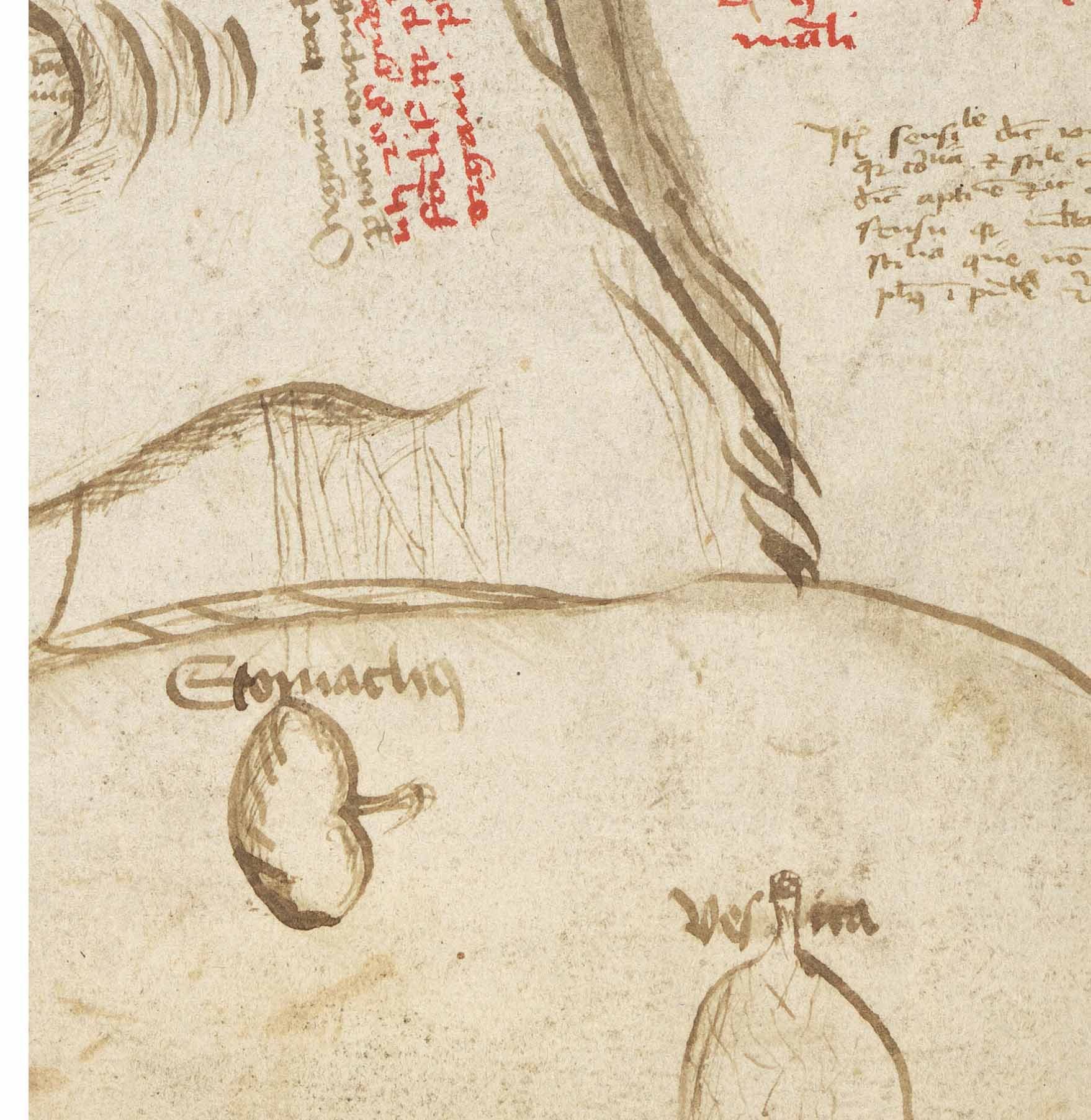

Figure 1. Aristotelian cardiocentrism vs various encephalocentric theories represented by an anonymous author in Gerardus Harderwyck’s Epitomata seu reparationes totius philosophiae naturalis Aristotelis, (Köln 1496). London, Wellcome Library, Shelfmark: Closed stores EPB/INC/2.b.5.

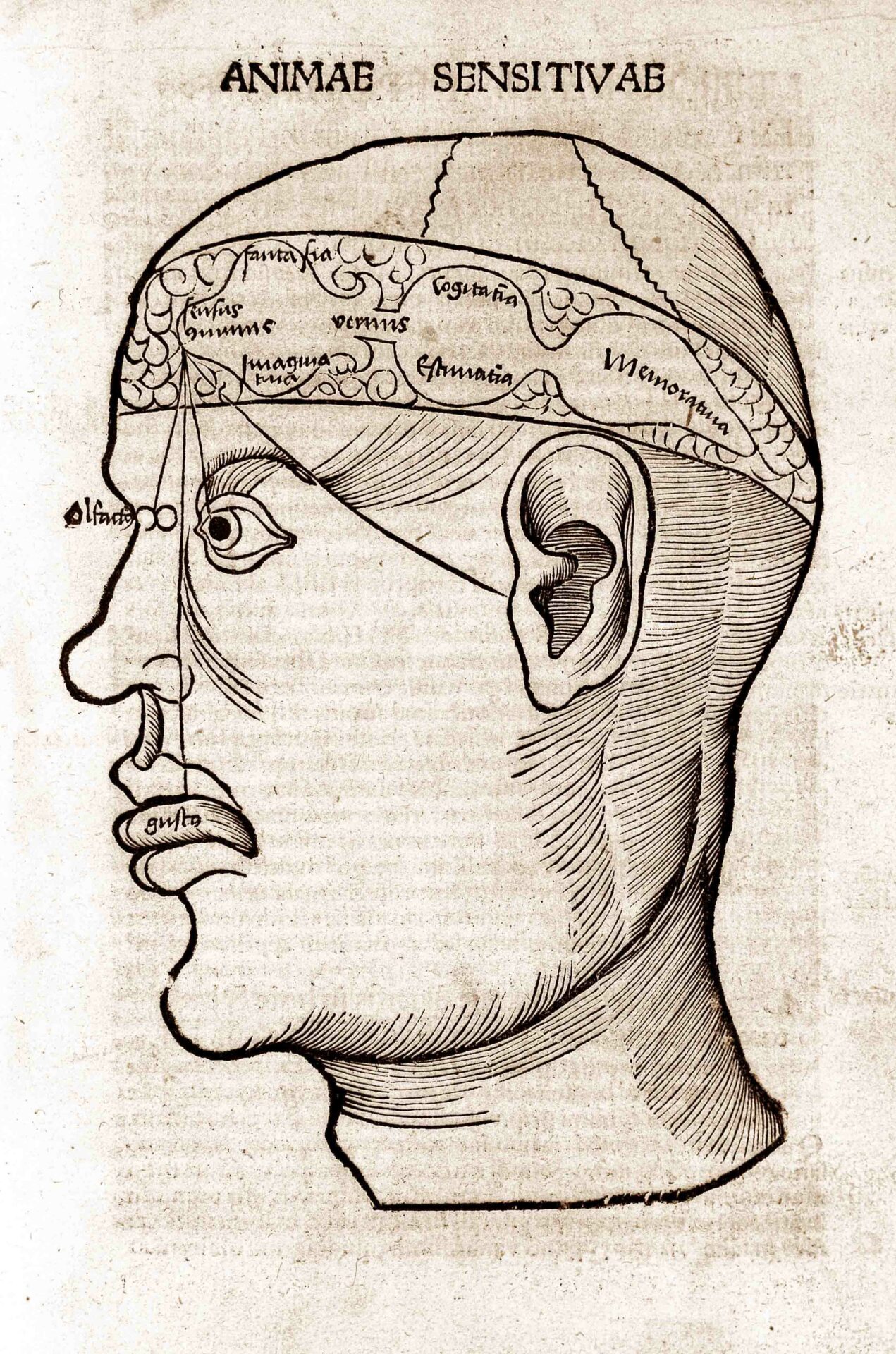

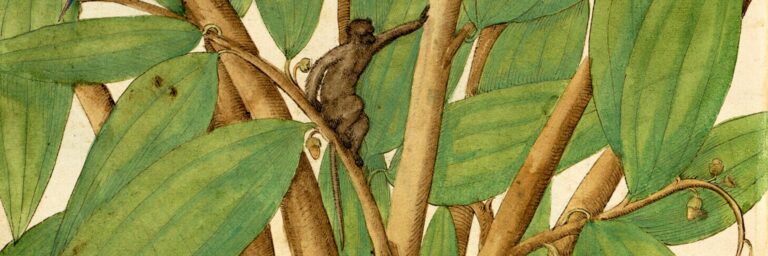

Figure 2. Woodcut of head showing cerebral ventricles, from Gregor Reisch’s Margarita philosophical (Freiburg 1503), X, II, 21. London, Wellcome Library, Shelfmark: Closed stores EPB/B/5409.

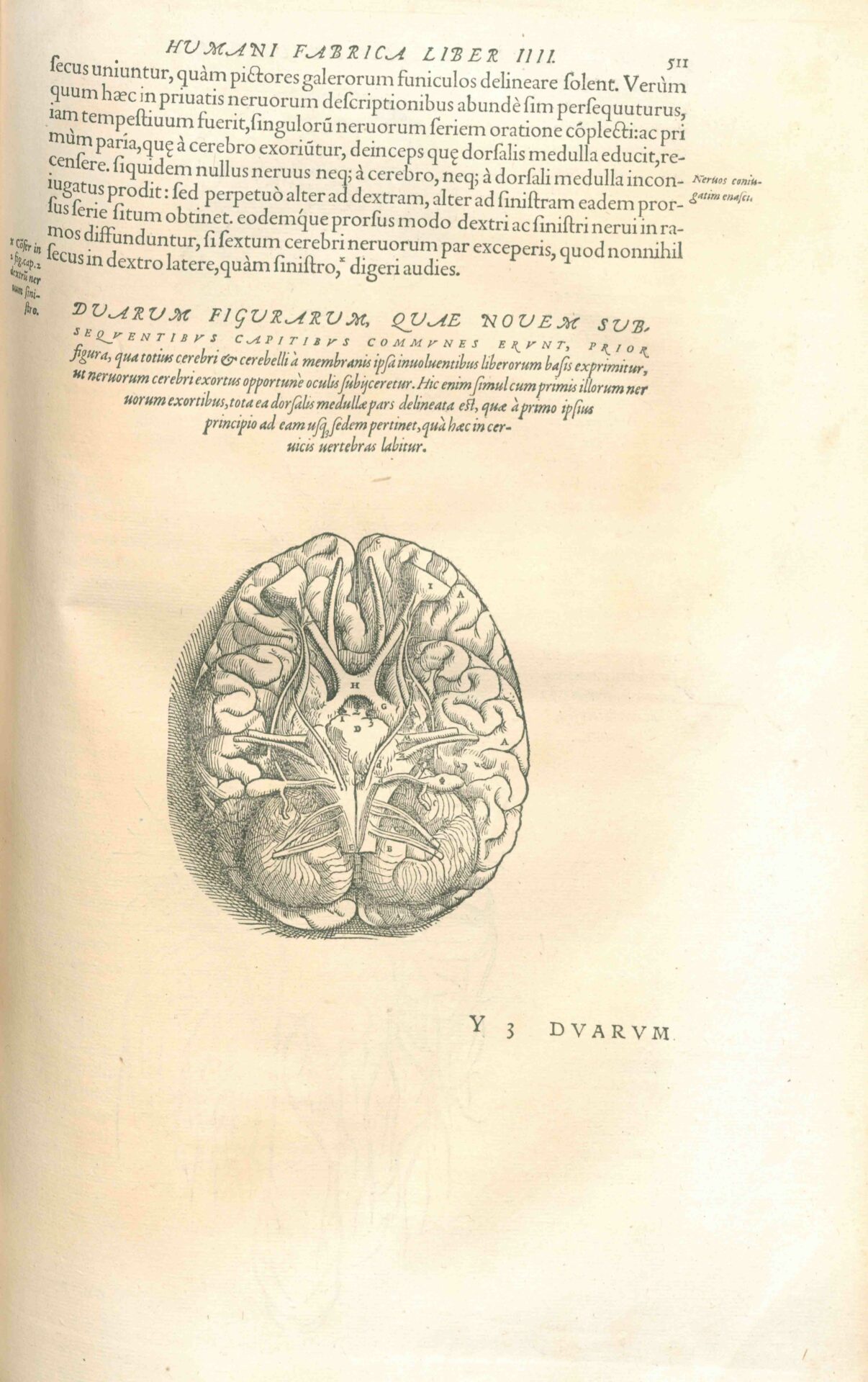

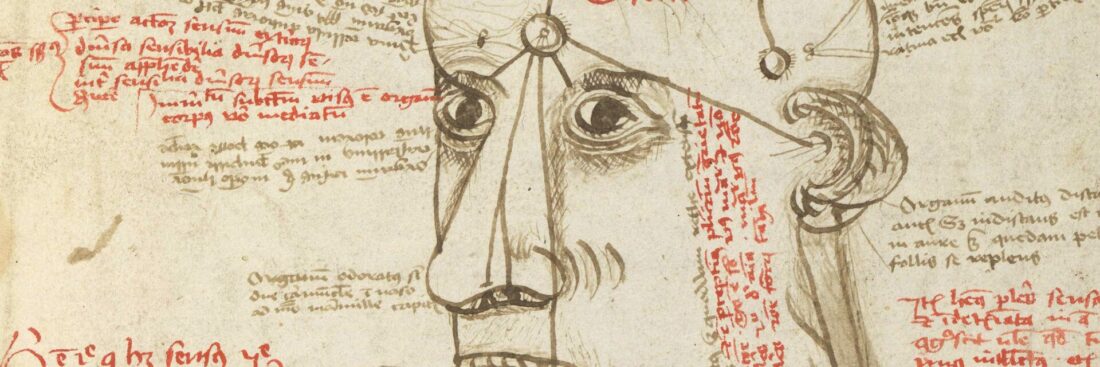

Figure 3. The optic chiasm from Andrea Vesalio, De humani corporis fabrica (Basel 1543), p. 511. London, Wellcome Library, Shelfmark: Closed stores EPB/D/6560.

Faced with such a contrast, Pomponazzi declares himself puzzled and deems any conciliatory solution absurd (valde ridiculum). He notes that Avicenna regarded Aristotle’s position as inherently true, whereas the physicians’ perspective appeared more evident and practically useful.[4] However, as a magister of natural philosophy, Pomponazzi is mainly interested in clarifying the proper Aristotelian thought. He therefore proposes two possible interpretations.[5] According to Averroes, even if Aristotle held that the common sense is originally (originaliter) placed in the heart, this does not mean it cannot manifest (manifestative) its power in the brain.[6] Pomponazzi does not reject this argument, but confesses his preference for a second and more radical interpretation: the common sense resides solely in the heart, with the brain acting merely as a refrigerator for the whole body.

Leonardo Graciotti is a PhD candidate in History of Philosophy and Science at the Università di Genova, in cotutelle with the Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. His research focuses on Pietro Pomponazzi’s last university course on the Aristotelian treatise De sensu et sensato (Bologna, 1524-1525) and, more broadly, on the reception of Aristotle’s libri naturales in the Latin West from the Late Middle Ages to the Early Modern Period. He is an Editorial Board Member of the journal Bruniania & Campanelliana.

Specifically, the brain supports the heart’s activity by regulating its heat via three ventricles: the anterior enables the common sense, while the central and posterior facilitate cogitation and memory. Therefore, brain’s injuries cause cognitive loss not because these functions reside in the brain, but because the damaged brain can no longer cool the heart, rendering it unable to perform its role.[7]

At this stage, Pomponazzi is bent on defending a radical form of cardiocentrism within the Aristotelian framework. However, in the following years, his perspective seems to shift slightly. The issue was taken up during his lectures on De partibus animalium (Bologna, 1521-1524). Pomponazzi remarks that, according to Aristotle, animal functions are driven by heat, with the heart being the hottest part of the body. By contrast, the brain’s coldness serves to prevent the body from being consumed by the heart’s heat.[8] However, physicians disagreed on this point: Galen considered the brain among the hot parts of the body; Avicenna attributed to it a lower degree of coldness compared to many other organs.[9] Thus, coldness itself could not be an obstacle to the brain’s perceptive faculty.

Furthermore, Plato argued that the brain is the centre of sense perception, given that three of the five senses—sight, hearing, and smell—are evidently located in the head. This led him to assume that taste and touch might also be closely connected to the brain, further supported by the fact that the head contains little flesh, which he considered a hindrance to sensory function.[10] Aristotle, however, replied by saying that the lack of flesh in the head has nothing to do with sensation: it depends on the brain’s need to perform its cooling function, which contrasts with the heat of the flesh.[11]

Once again, Pomponazzi reiterates Aristotle’s view that the heart is the seat of sense perception and, more broadly, the principle of animal’s life—as indicated by its central position in the body. However, while he cautiously accepts this perspective as plausible, though not conclusive, he also acknowledges that sight, hearing, and smell clearly occur near the brain. This is evident in the case of vision, for the eye’s substance is cold and moist (aqueous), much like the region around the brain.[12] Moreover, sight is the noblest of the senses, requiring nearly cold and refined blood (sanguinis tendente ad frigiditatem et sincero) that circulates through the tiny blood vessels of the brain’s meninges, such as the pia mater and dura mater.[13] Pomponazzi is now more inclined to recognise a significant role for the brain in sense perception.

The question was raised again, for the last time, in his university course on De Sensu et sensato (Bologna, 1524-1525). In this short treatise, which opens the Parva naturalia collection, Aristotle himself placed the sense of sight, hearing and smell in the brain, while assigning touch and taste to the heart. Does this mean he acknowledged two distinct principles at the origin of sense perception? Not quite. Pomponazzi suggests a distinction between principle (principium) and organ (organum).

The heart is the source of life, blood, heat, and sense perception. The sensitive faculty reaches its peak in the heart—the house of the common sense—but perception itself does not occur directly within the heart. Instead, the power of perception is transmitted from the heart to the other parts of the body through the nerves, whose origin is found by Aristotle in the heart, while Galen and the physicians traced it in the brain.

Additionally, the heart is the organ of touch and taste, that is, the primary instrument through which tactile and taste perceptions are realized (along with secondary instruments such as palm, tongue and so on). As for sight, hearing and smell, the heart remains the underlying source, but the actual organ responsible for these perceptions is the brain.[14]

According to Pomponazzi, the brain’s crucial role in sense perception is demonstrated by its ability to unify sensory data coming from external objects: since the sensible forms (species sensibilis) are collected in a dual manner by eyes, ears, and nostrils, there must be a single organ capable of bringing them back to unity. Pomponazzi explains that, although Aristotle did not make it clear, it is evident that he identified the optic chiasma (incruciatio nervorum)—the junction of the optic nerves in the brain—as the place where vision actually occurs. And the same could be said for hearing and smelling.[15]