The Medicine of Merchants

FORMA FLUENS

Histories of the Microcosm

The Medicine of Merchants

Health, Spices, and Commerce

in the Late Middle Ages

Massimo Sbarbaro

University of Ljubljana

In the collective imagination, the medieval merchant is often associated with distant trades, oriental silks, money, and bookkeeping. Yet, if we delve into the pages of trade manuals, family memoirs, and the personal notebooks (zibaldoni) compiled by these businessmen between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, a less expected dimension emerges: merchants were not only concerned with fabrics and spices but also with health and medicine.

Medieval trade was far from risk-free: long journeys, unhealthy environments, frequent epidemics, and poor hygiene conditions made it imperative for merchants to develop a solid body of practical knowledge concerning preventive medicine, the management of common illnesses, and the very commerce of therapeutic substances. It is no coincidence that some of the most valuable goods transported over land and sea were directly linked to health: ginger, pepper, aloe, theriac, galbanum, opium, and countless other medicinal “simples” filled the shelves of apothecaries.

The relationship between trade and medicine in the mercantile society of the late Middle Ages was close and well-developed. Drawing on three major sources—the Pratica della mercatura by Pegolotti, the Ricordanze of Giovanni Morelli, and two zibaldoni compiled by merchants and local elites—this article explores how medicine was for merchants not only a matter of commerce but also a form of practical knowledge and a crucial component of personal and collective survival.

The Merchant as Health Manager

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, merchants were more than sellers or money changers. They were multifaceted figures: entrepreneurs, diplomats, explorers, experts in metals and weights, men of letters, and—less commonly acknowledged—managers of their health and that of their families and business networks.

Major mercantile companies, such as those of the Bardi, the Peruzzi, or Francesco Datini, maintained branches across the Mediterranean and Europe: from Avignon to London, from Tunis to Bruges. Each branch operated semi-autonomously, handling complex operations including health risk management—knowing the origin and efficacy of drugs, when to avoid plague-stricken areas, and how to store medicines in port warehouses or ship holds.

Merchants were expected to:

-

- assess the quality of saffron or opium;

- distinguish genuine balsam from forgeries;

- protect their personnel during travels in hot or damp climates;

- record and transmit medical advice to children and relatives across branches.

Trade manuals did more than discuss prices and currency exchanges. They included entire catalogues of medicinal spices and drugs. When they did not, merchants compensated with their own collections—zibaldoni—or in letters describing remedies, symptoms, and preventive measures.

Spices and Drugs: The Commerce of Health

In the Middle Ages, spices and drugs were not merely luxury items—they were central to traditional pharmacology. Galenic and Hippocratic medicine classified substances according to their effects on the four humours: hot/cold, dry/moist. Thus, pepper “warmed” and aided digestion; ginger counteracted stomach coldness; cinnamon served as an antiseptic; clove had analgesic properties; and aloe was a purgative. Even the famed castoreum (a secretion from beavers), listed in commercial inventories, had recognized therapeutic uses.

The Pratica della mercatura by Francesco Balducci Pegolotti [1]—written in the early fourteenth century—meticulously lists hundreds of tradeable goods, including:

-

- Theban opium

- Saffron

- Carpobalsam

- Theriac (otriaca)

- Storax

- Galbanum

- Terra sigillata (a medicinal clay)

Pegolotti did more than name these goods: he described their weights, measures, prices, and qualities, and offered practical advice on how to handle them in trade.

The Libro di mercatantie et usanze de’ paesi,[2] compiled about a century later, updates these lists and confirms the persistence of medical commerce: items like “fine theriac,” “refined spices,” and “medicinal clays” remained central in trade. Practical management was equally detailed, requiring careful weighing of minute spices with the container’s weight (the so-called tara) deducted, proper sealing of all containers, and attention to preservation conditions for sensitive drugs, particularly during extended maritime voyages.

Manuals, Letters, and Branches: Medicine at the Heart of Business

Late medieval trading companies—such as those of the Bardi, Peruzzi, Acciaiuoli, and to a lesser extent but much better known the well-documented Datini[3]—operated as early multinational enterprises. They maintained branches in multiple cities, connected by a dense network of correspondence and standardized accounting records.

Each branch had to function efficiently, adapting to local customs, currencies, and health risks. Therefore, in addition to ledgers and cashbooks, branches maintained:

-

- trade manuals explaining how to handle drugs and spices;

- practical health instructions (not formally codified, but gleaned from letters and zibaldoni);

- up-to-date lists of the most demanded medicinal substances in different ports.

These manuals did not merely record prices. They included storage techniques: how to seal barrels of medicinal syrups, or how to distinguish genuine ambergris—used in medicines and perfumes—from counterfeits.

Correspondence between branches often referenced health concerns: alerts about approaching plague, advice to avoid certain routes, requests for theriac, or orders of warming spices for preventive use.

Commercial shipments, then, were also therapeutic shipments, and merchants were not just vendors: they used the medicinal products they traded.

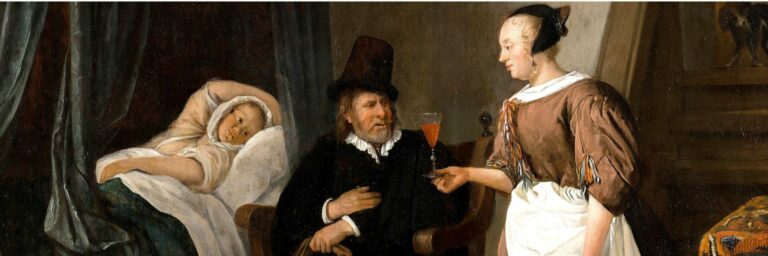

The Plague from a Merchant’s Perspective: Giovanni Morelli’s "Ricordanze"

Giovanni di Paolo Morelli, a Florentine merchant who lived from 1371 to 1444, left behind a remarkable family record: the Ricordanze.[4] It contains not only business dealings and personal recollections but also detailed health advice.

Morelli lived through several waves of plague and left his children clear instructions for prevention, based on both contemporary medical theory and personal observation: [5]

-

- Avoid cold and damp environments;

- Light fires every morning at home to purify the air;

- Avoid heavy foods;

- Eat only a little bread and wine in the morning;

- Use theriac (“a bit of theriac”) during damp periods;

- On an empty stomach, consume candied ginger with malmsey if the stomach is “cold”;

- Chew cloves or cinnamon.

These instructions align perfectly with humoral medicine. What is striking, however, is that they were written not by a physician but by a merchant.

Morelli also urged against improvisation: he advised his sons to consult physicians and obtain written instructions to follow strictly.[6]

Massimo Sbarbaro, a specialist in digital humanities and late medieval history, holds a PhD from Trieste and is pursuing a second doctorate in digital linguistics at the University of Ljubljana. His research merges computational methods and historiography to analyse 13th–15th-century fiscal systems and notarial sources. He has published on coinage, taxation, and the Fourth Crusade and has presented widely in Italy and Slovenia. He works in Italian, English, Slovenian, and Latin.

He compared prevention to wearing armour in battle: it does not guarantee survival, but it improves the odds.

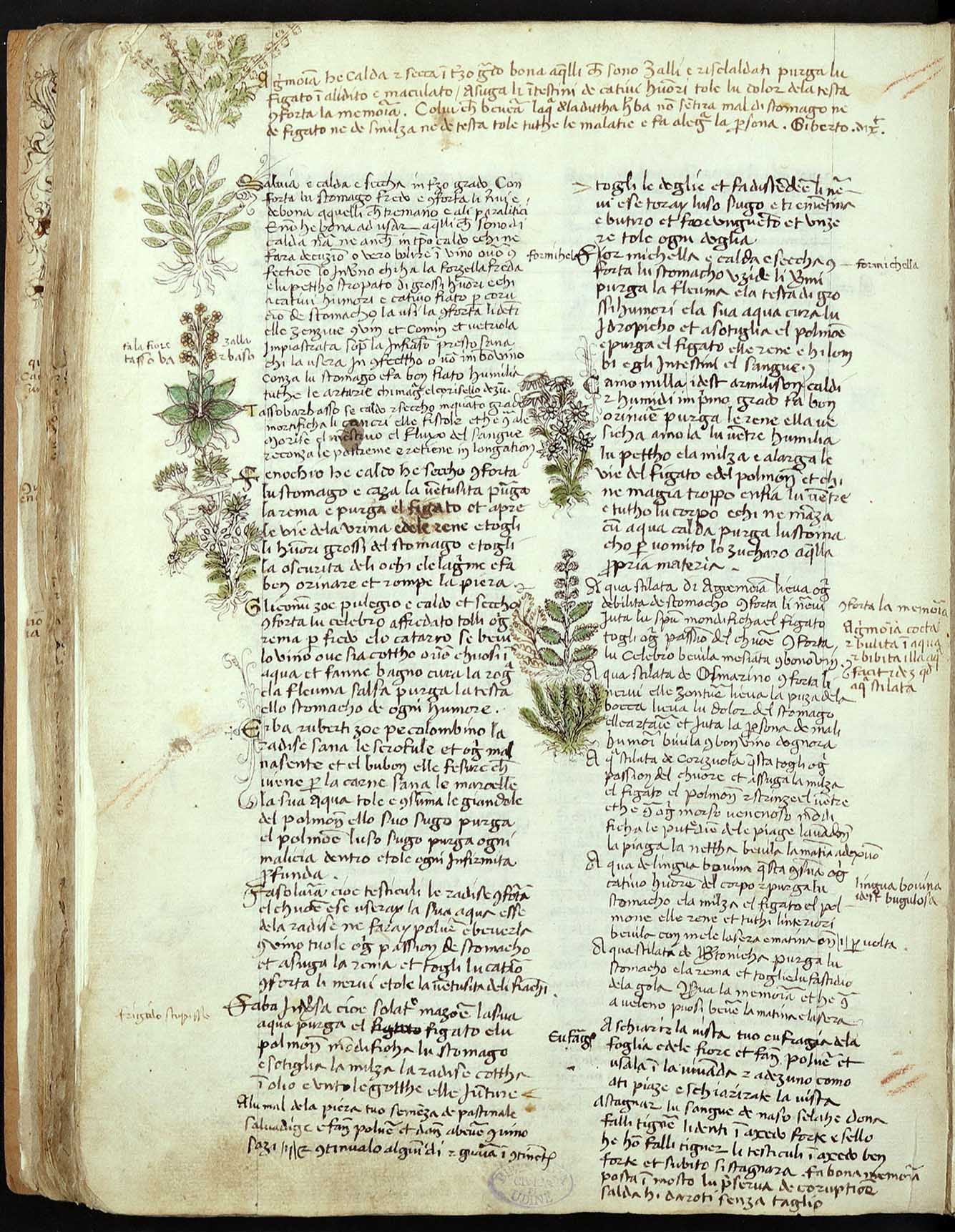

Mercantile "Zibaldoni": Medicine in the Workshop Notebook

In addition to major trade manuals and scholarly treatises, a rich and often overlooked source of late medieval medical knowledge lies in zibaldoni—personal and family collections compiled by merchants, notables, artisans, and practically-minded individuals. These were not scientific works but mixed notebooks, written in the vernacular and intended for everyday use. These notebooks included a diverse array of content—commercial notes, proverbs and moral sayings, medical and cosmetic recipes, arithmetic exercises, and religious or literary excerpts. Several examples highlight how medicine entered these texts compiled by laypeople.[7]

Francesco Bentaccordi: Between Avignon and Practical Pharmacy

A Florentine merchant living in Avignon, Francesco Bentaccordi[8] compiled a manuscript (Archives dép. Vaucluse, MS I F 54) that forms a miniature world. It includes excerpts from Dante, trade exercises, personal notes—and medical recipes.

Bentaccordi did not organize these recipes systematically. He jotted down remedies wherever space allowed, often alongside moral reflections or household accounts. This indicates a practical, non-specialist engagement with medicine—focused on survival, not dissemination.

He likely acquired his remedies from oral traditions in Florence and physicians and apothecaries in Avignon. The texts are written in Tuscan vernacular with French influences, evidencing the European circulation of medical knowledge.

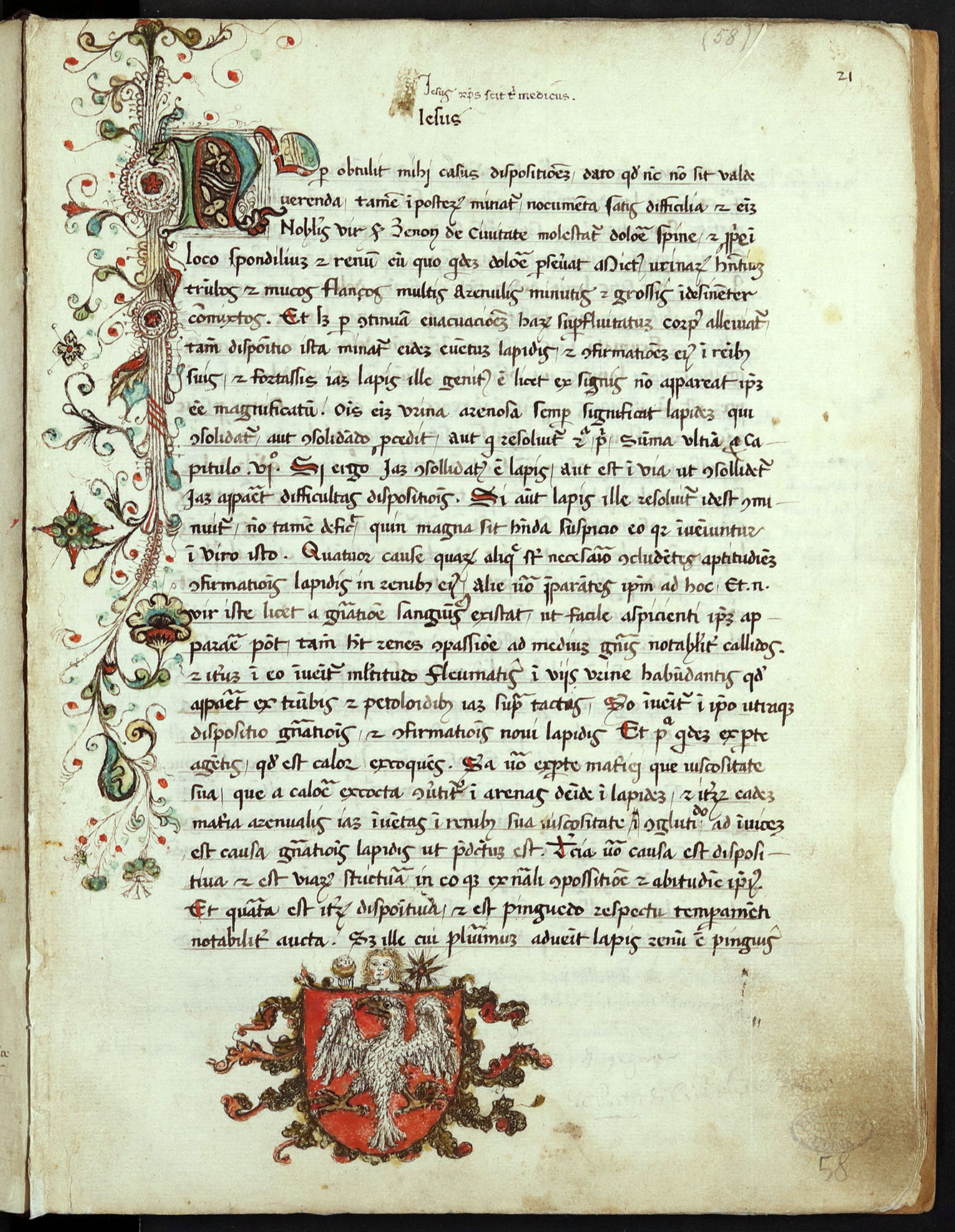

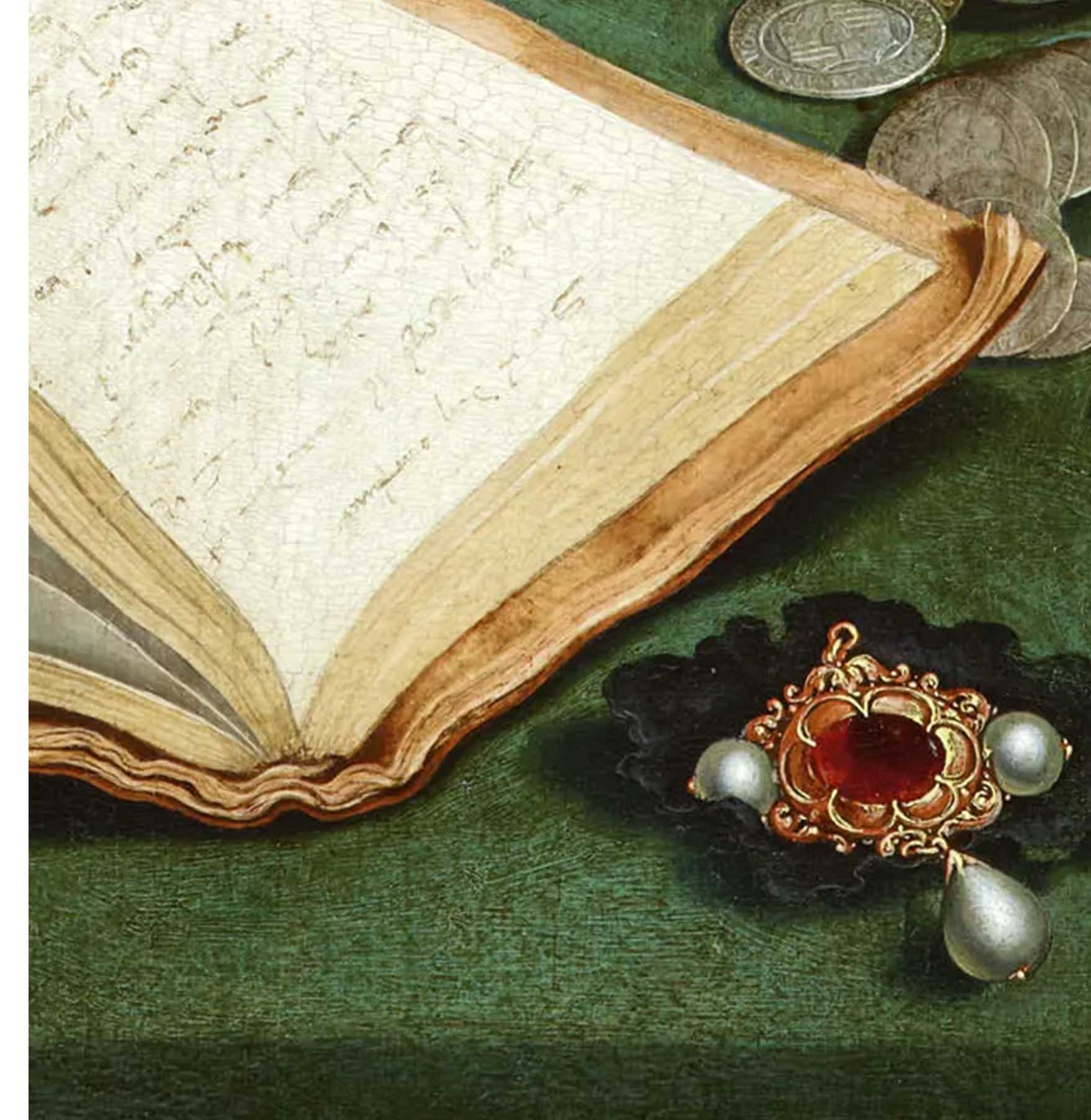

Nicolò de Portis: Kidney Stones and the Memory of Healing

The second zibaldone is that of Nicolò de Portis[9], a Friulian nobleman, begun in 1441 (Udine, Biblioteca Civica, MS Joppi 61, Figs 1-2). Both Nicolò and his father suffered from kidney stones (“mal della pietra”). To treat this, his father consulted Bartolomeo da Montagnana, a prominent physician at the University of Padua, who wrote a personalized consilium. Nicolò copied it in full, commented on it, and added his observations.

At one point, he writes: “Non voyo che sia dismentegata questa medicina” (“I do not want this remedy to be forgotten.”) This reveals his intent: to preserve medical knowledge for future generations and turn family experience into collective heritage.

The manuscript contains recipes in Venetian dialect, local names alongside Latin terms as well as observations on contemporary physicians and treatments.

In his will, Nicolò described himself as “languens” (ill) and was surrounded by two doctors, two barbers, and a surgeon—indicating a multidisciplinary model of care typical of late medieval Italy.

Figure 1-2. Nicolò de Portis’ Historia Varia (1470), MS 61, cc. 21v, 30r. Courtesy of Biblioteca Civica di udine, ‘Vincenzo Joppi’.

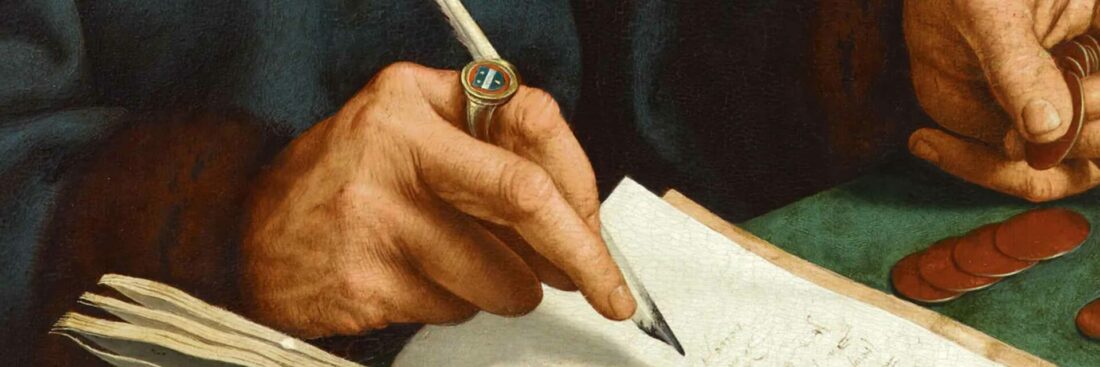

Figure 3. Niccolò di Pietro Gerini, Banco dei tributi (‘Tax Collection Office’, c. 1395-1400), detail from the Fresco ‘Conversione del levita Matteo’, Saint Matthew’s Histories, Migliorati Chapel – Prato.

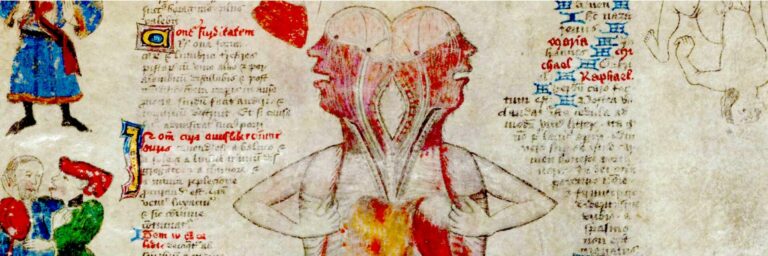

Merchants as Bearers of Medical Culture

From the analysis of trade manuals, personal memoirs, zibaldoni, and letters, a clear picture emerges: the medieval merchant was a transmitter of medical culture, even if not a physician by training. This culture was not academic but practical, multilingual, and adaptive: in trade manuals, medicine and commerce intersect through detailed spice lists; in family records, health precautions are transformed into life instructions; and in zibaldoni, medical knowledge circulates as a treasured and preserved resource.

Merchants were not mere intermediaries. They translated, adapted, verified, and preserved medical knowledge. Latin treatises became vernacular instructions—in Venetian, Florentine, or Ligurian dialects. University medicine was recorded, annotated, and disseminated beyond scholarly circles.

Owning a medical recipe book signified autonomy but also respect for professional expertise. As seen with Nicolò de Portis, merchants preserved both household remedies and consilia from renowned doctors—bridging lay and learned traditions.

In the late Middle Ages, medicine was both a commercial asset and a survival strategy. For merchants, health was a capital to be protected, much like goods, credit, or honour. The surviving texts—from Pegolotti’s treatise to Friulian zibaldoni—reveal a society where the boundary between merchant and healer was more fluid than we might imagine.

In apothecaries’ shops, business letters, and personal notebooks, a composite therapeutic knowledge circulated—tailored to everyday needs. This knowledge moved, from universities to marketplaces and from Latin treatises to vernacular translations, and, finally, it relocated from specialists to literate laypeople.

The medieval merchant combined numerical acumen, the curiosity of a traveller, and care for body and community. In his hands, theriac was not merely a product to sell, but a potential defense against death. Ultimately, these merchants appear as integrated managers of economy and health. Their legacy reminds us that, in the Middle Ages, survival was a cross-disciplinary competence, and knowledge—including medical knowledge—was inseparable from the art of living.