The Language of the Universal Cure

FORMA FLUENS

Histories of the Microcosm

The Language

of the Universal Cure

Alchemical Terminology in

Seventeenth-Century Naples

Elena Morgana

University of Oxford

Comèl Grant

The quest to extract the purest essence from plants, animals, and minerals in order to produce the most comprehensive and potent cure imaginable has long been a central aim of medical alchemy. Although this pursuit remained consistent, the methods and philosophical foundations underpinning it evolved considerably over time. In the seventeenth century, such was the focus that the process of extracting the Elixir, the name given to this almost mythical universal remedy, became as much a subject of inquiry as the Elixir itself. In Naples, a city alive with intellectual exchange, intersecting trade routes, political upheaval, and a deeply embedded pharmacological tradition, this discourse found especially fertile ground. The city not only absorbed external influences but also developed its own distinct identity and trajectory in medical practice, shaped by its particular socio-political context and influential figures.

The city’s intellectual climate was notably receptive to chemical and alchemical theories of transformation and refinement. The Kingdom of Naples fostered a robust tradition of both herbal remedies and chemically derived cures; figures such as Giovanni Battista della Porta and Ferrante Imperato had already laid important groundwork in the late sixteenth century, by promoting collections and detailed analyses of natural substances, thereby encouraging a culture of intellectual exchange. Simultaneously, surgeons like Marco Aurelio Severino, an advocate for chemical medicine, sought to challenge traditional practices by arguing that medicines should be chemically purified and transformed. However, his views met resistance from more traditional practitioners such as Carlo Pignataro, who adhered to ancient humoral theory and herbalism. [1]

Amidst this ongoing debate, Fra Donato d’Eremita (active 1611-1630), a Dominican friar from Rocca d’Evandro, played a pivotal role in advancing the practice of chemical purification and remedy-making, particularly through his innovations in laboratory apparatus and distillation techniques. His early experience at the convent of Santa Maria alla Sanità, which was known for its flourishing apothecary and herb garden, provided a strong foundation for his later work. In 1611, he moved to Santa Caterina a Formello, where he took charge of a newly established herb garden and apothecary, quickly gaining recognition for his healing preparations. His most significant legacy is the treatise Elixir Vitae, published in 1624, following his Antidotario (1616) and a work on distilling techniques, Dell’Arte Distillatoria (1617).[2]

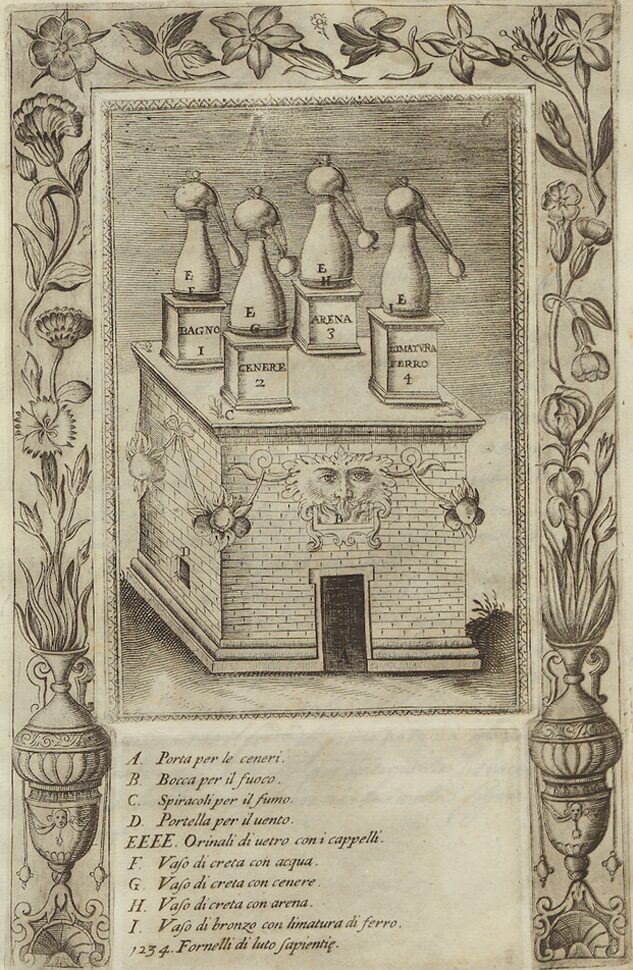

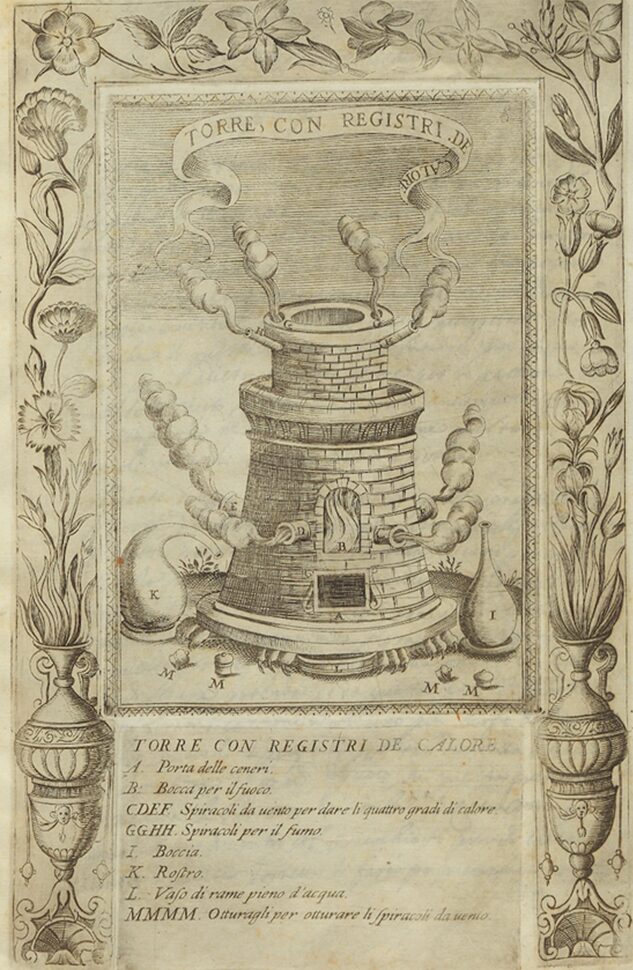

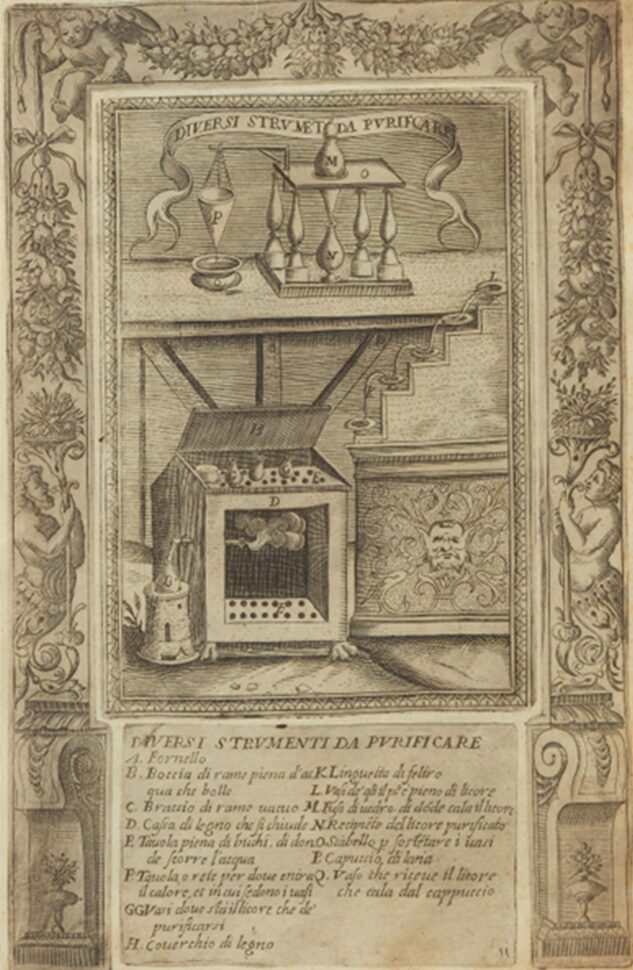

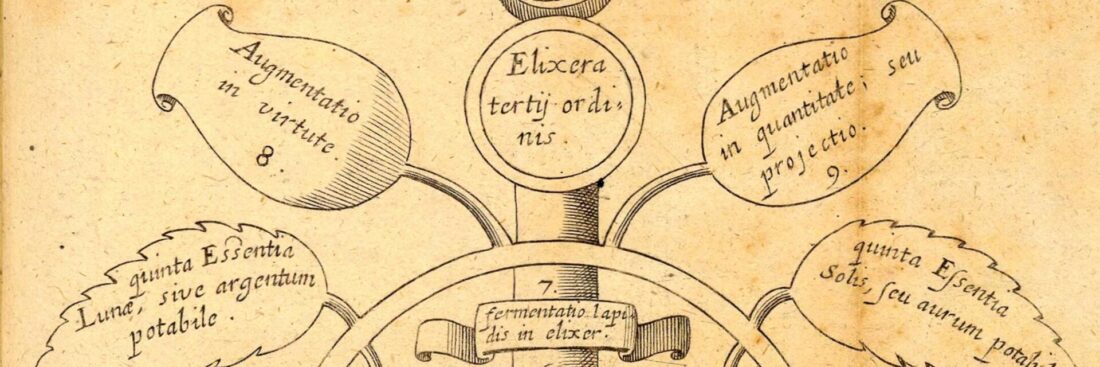

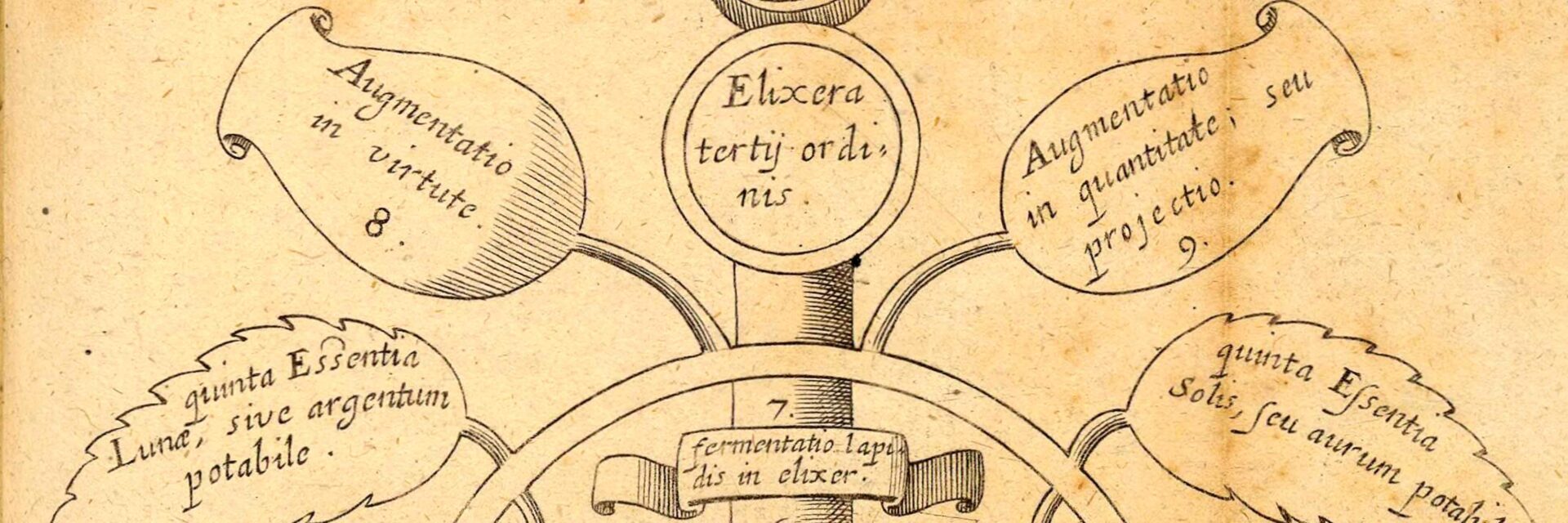

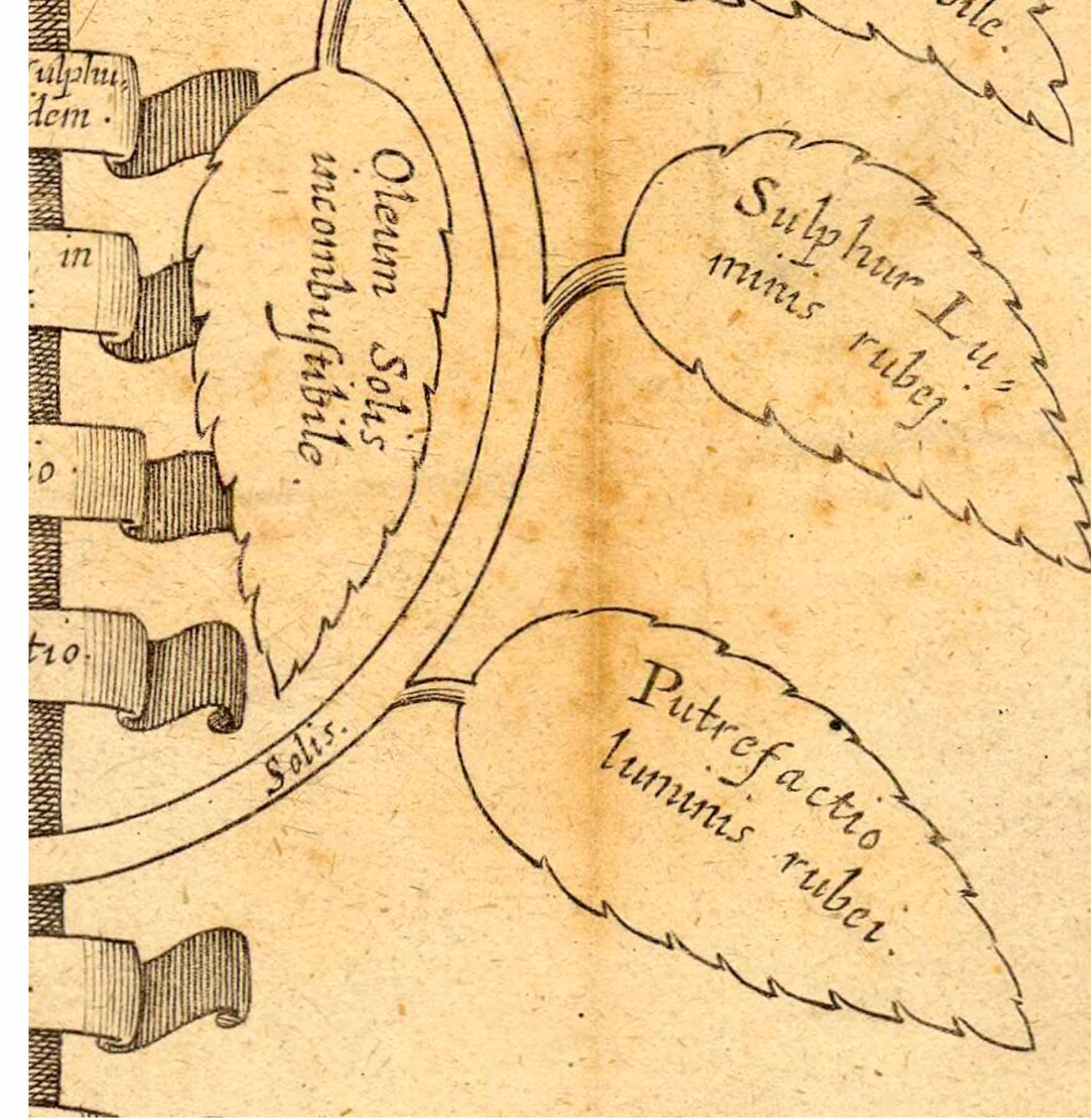

The text of Elixir Vitae is accompanied by twenty-eight detailed engravings illustrating the apparatus required for Donato’s distillation method. These images depict preparations involving solvents such as aqua vitae, a sublimated essence “made to appear as a liquid that… in antipathy with a diseased humour it drives it away like an enemy.”[3] This solvent underwent several stages of purification and was regarded not merely as a tool but as a potent and active agent within the alchemical process. Donato argued that the artificial heat of distillation enabled the practitioner to separate the gross from the essence in a fraction of the time. Through this laboratory technique, he claimed, human intervention could even surpass nature.

Figure 1-3. Engravings from Donato D’Eremita Dell’Arte Distillatoria MS 16.22. I. lh. Biblioteca dell’Archiginnasio, Bologna. The same illustrations are also included in the published version of Elixir Vitae, pp. 19, 23, and 38.

Figure 4. Frontispiece of Giuseppe Donzelli, Teatro farmaceutico dogmatico, e spagirico (Rome , Felice Cesaretti: 1677).

In the opening chapters of Elixir Vitae, Donato offered several definitions for the famous Elixir. He calls it quinta essenza (quintessence), describing it as a heavenly element, created through art, that preserves and strengthens the body while destroying diseases. He also referred to it as Mercurio vegetabile (Vegetable Mercury) to highlight its transformative power, claiming it enhances the virtues of everything it touches. Additionally, Donato used the term acqua menstruale (menstrual water), suggesting that the Elixir mixes with a liquid, becoming drinkable and taking on the qualities of that liquid, whether hot or cold. This might imply that he believed the Elixir interacted with both the body’s humours and the liquid it is combined with. In line with the Rupescissan tradition, Donato stated that the most perfect quintessence is found in wine, which possesses qualities that help preserve the body, and that it could also be called Aqua Vitae—the water of life.[4] In this process, the aqua vitae (or quintessence) extracts the essence of the ingredients, which are then infused in menstrual water for several days, allowing it to absorb their active properties.

Such definitions being included in a cornerstone Neapolitan work on distillation, contributed to a terminological puzzle in which the concepts of quintessence and the Elixir became increasingly intertwined. Traditionally, the Elixir was associated with healing properties and the restoration of vitality, while quintessence referred to the purest, most concentrated essence derived from a substance. In practice, however, these distinctions were often blurred, leading to significant ambiguity—especially in the Kingdom of Naples.

As the concept of the Alkahest, the universal solvent popularised by Jan Baptist Van Helmont (1580–1644) in Ortus Medicinae (1648), gained traction across Europe, the ambiguity surrounding the terms “Elixir” and “Quintessence” deepened. Van Helmont equated his concept of ignis aqua (fiery water) with the Alkahest, using it as a synonym for the universal solvent in De Lithiasi and referring to it as “liquid fire” (liquor ignis). While ignis aqua appears similar to the spiritus vini (spirit of wine) or aqua ardens of Rupescissa, Van Helmont described it as a singular, immortal, and unchanging substance, imbued with spiritual implications.[5]

This led to debates, with the German physician Otto Tachenius (1625–1700) accusing Van Helmont in his Epistola de Famoso Liquore Alkahest (1677) of concealing his use of Mercury.[6] Tachenius suggested that Van Helmont never fully explained his process and might have hidden the concept of Philosophers’ Mercury under that name. Tachenius later collaborated with Van Helmont’s son, Franciscus Mercurius, and it is likely that the posthumous edition of Ortus Medicinae, edited by both Franciscus Mercurius and Tachenius, circulated among Neapolitan alchemists; Tachenius himself had been invited to the city by Marco Aurelio Severino, with whom he maintained correspondence. As Helmontian literature spread, so too did its criticisms, causing terms like Elixir and Alkahest to appear in the same texts and medical circles. The uncertain identity of the Alkahest did not deter others from attempting to replicate it, particularly in contexts where public health crises demanded new remedies.

After earning her Master’s degree in Cultural, Intellectual, and Visual History from the Warburg Institute in 2023, Elena Morgana is currently pursuing a DPhil at the University of Oxford, delving into the late 17th-century alchemical quest for the liquor Alkahest, believed to be a universal solvent. Elena’s research focuses on the diverse conceptions of this substance and its evolution from a simple medical substance to a loaded symbol of purification, exploring the rich allegorical layers that have been woven into its history.

A strong proponent of the rebellion was Giuseppe Donzelli (1596–1670), a doctor who, in his later years, returned to the study of chemistry, believing that medicine should be closely tied to scientific research. Donzelli became a leading expert in pharmacological botany and herbalism, working to integrate medicine, pharmacology, chemistry, and botany. By the late 1630s, he was well-known and had established a renowned medicinal plant garden at his villa in Arenella (Giardino dei Semplici). In 1640, the Kingdom’s highest medical authorities entrusted Donzelli with the task of composing an official Antidotario or Petitorio—an officially recognised medical formulary that all medical professionals were required to follow. Naples lacked such a resource, with the only existing version, dating back to 1614, being outdated and available only in manuscript form. This created confusion and uncertainty among apothecaries, often leading to abuses, disputes, and inefficiencies. Donzelli completed his work, and in 1642, he published the Antidotario napolitano. His most significant work, Teatro Farmaceutico, was published in 1667, though it is evident that he had been working on earlier versions of the text since the 1640s. The work lived up to its title, offering a comprehensive view of the medical landscape in the Kingdom of Naples.

Early in the text, Donzelli expressed scepticism towards the Alkahest as a universal medicine capable of granting longevity. His doubts likely stemmed from his reading of Van Helmont, whose writings are themselves marked by ambiguity. While Van Helmont claimed that “at length I perceived, that the liquor Alkahest did cleanse Nature, by the virtue of its own Fire: For as the Fire destroyeth all Insects, so the Alkahest consumeth Diseases,”[7] he ultimately did not present the Alkahest as a cure in itself, but rather as a powerful solvent used to extract the true life-prolonging substance—the Arbor Vitae. Donzelli’s misreading of this distinction may account for his reservations. In his discussion of quintessence, Donzelli draws on both the Rupescissan tradition and contemporary interpretations of the Alkahest. He observes that spirit of wine is the standard menstruum used to extract the essence of various aromatic substances, which are subsequently referred to as aqua vitae or, more frequently, elixir vitae. He describes this substance as “fiery water.” In doing so, he once again merges the concepts of elixir and quintessence, as seen in Fra Donato’s work, while also acknowledging the contributions of contemporary figures such as Johann Rudolph Glauber (1604-1670), who traced the origins of the Alkahest to the products of wine.[8]

Donzelli’s strategic placement of references to the Alkahest within the more theoretical sections of his work suggests that, although his principal aim was the cure of disease, he remained fully aware of the broader alchemical and philosophical dimensions underpinning his materia medica. Interestingly, rather than consistently referring to the Alkahest, Donzelli proposed several elixirs that nonetheless embodied Helmontian attributes typically associated with the Alkahest. This reveals how the concept remained influential even when expressed through older, more familiar terminology—perhaps more acceptable to the Neapolitan medical community who would have relied on his text in their practice. Notably, Donzelli introduces a recipe for Elisir di Vita Maggiore, a Neapolitan iteration of the Elixir Vitae. After presenting the recipe, he is careful to explain why he uses the term Elixir Vitae “by analogy.” He notes that while some authors refer to mixed aqua vitae as an Elixir, his usage is more specific.

For Donzelli, the Elixir does not merely denote a composite quintessence, or spirit of wine, but a substance associated with the “renovation and promulgation of life”,[9] concepts aligned with the Paracelsian and Helmontian theories of universal medicine. He distinguishes this Elixir from simple solvents such as the Alkahest or aqua vitae, emphasising its compounded nature and its life-renewing properties, which he believed justified the title Elixir Vitae. It was said to treat a broad range of ailments, including epilepsy, vertigo, apoplexy, paralysis, and general physical pain. Administered in small doses and diluted with water or wine suited to the condition, the Elixir Vitae served as a powerful treatment for a host of serious disorders. Nevertheless, after enumerating the specific illnesses it addressed, Donzelli acknowledged its limitations, recognising that despite its potency, it was not a universal cure.

Donzelli presents another recipe for an elixir, the Elixir Proprietatis, referring to it as the Elixir of Van Helmont. Originally conceived by Paracelsus, the Elixir Proprietatis, typically made with ingredients such as aloe, myrrh, and saffron, was intended not only to heal but also to restore vitality, including the renewal of hair, nails, and teeth. Van Helmont, however, criticised it as superficial: while it could rejuvenate certain aspects of the body, it failed to genuinely prolong life or halt the decline of vital powers. Van Helmont compared the Elixir Proprietatis to a mere solvent, taking care to distinguish between remedies that addressed specific diseases and those that could extend life itself. Yet, in a later section of the Ortus Medicinae, he revised this view, suggesting that the Elixir Proprietatis could indeed function as a life-extending cure—but only when prepared using the Alkahest.[10]

Donzelli recognised the symbolic and theoretical significance of such medicaments but rather focused on their application in treating concrete ailments. His version of the Elixir Proprietatis was accordingly adapted for greater therapeutic effect, substituting ingredients such as spirit of wine in place of cinnamon water to enhance its potency. In Naples, Donzelli’s version of this cure gained widespread popularity and was even modified by local physicians, including Sebastiano Bartoli, who experimented with altering its components. It developed a strong reputation for treating a range of conditions: it was believed to protect against the plague, purify the air, and heal wounds and ulcers.[11] While Donzelli did not widely use the Alkahest, his work reflects the growing influence of Helmontian ideas on solvents. While he sometimes contradicted himself, switching between Galenic and Paracelsian doctrines, his aim was not to reform but to maintain a high standard of practice. The concept of the Alkahest may not have fully taken root, but it certainly sparked a re-evaluation of solvents, stimulating the evolution of both practice and understanding.

Linguistically, the term Alkahest was never fully integrated into the medical vocabulary of the Kingdom of Naples, largely due to the absence of a stable, reproducible recipe. However, the conceptual understanding of solvents and their active properties underwent a notable transformation. Solvents were no longer characterised solely as aqua ardentes (flammable liquids) with corrosive effects, but increasingly came to be associated with purifying and transformative powers, thereby expanding the term’s significance. Ultimately, the critical attention Neapolitan medical practitioners paid to language shaped their understanding of chemical substances. They were compelled to interrogate both the meaning and function of key terms in order to establish a shared lexicon for foundational texts in chemical practice. This process not only refined their own methodologies but also contributed to a broader standardisation of medical discourse across the professional community.