Naming Cancer (13th-14th Centuries)

FORMA FLUENS

Histories of the Microcosm

Naming Cancer between

the 13th and 14th Centuries

Lupus and Nosological Ambiguities

Claudio Zabatta

University of Bologna

Comèl Grant

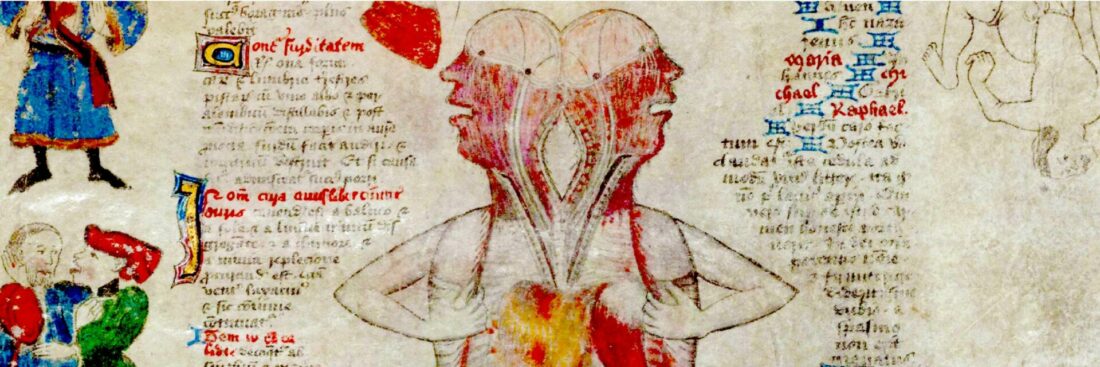

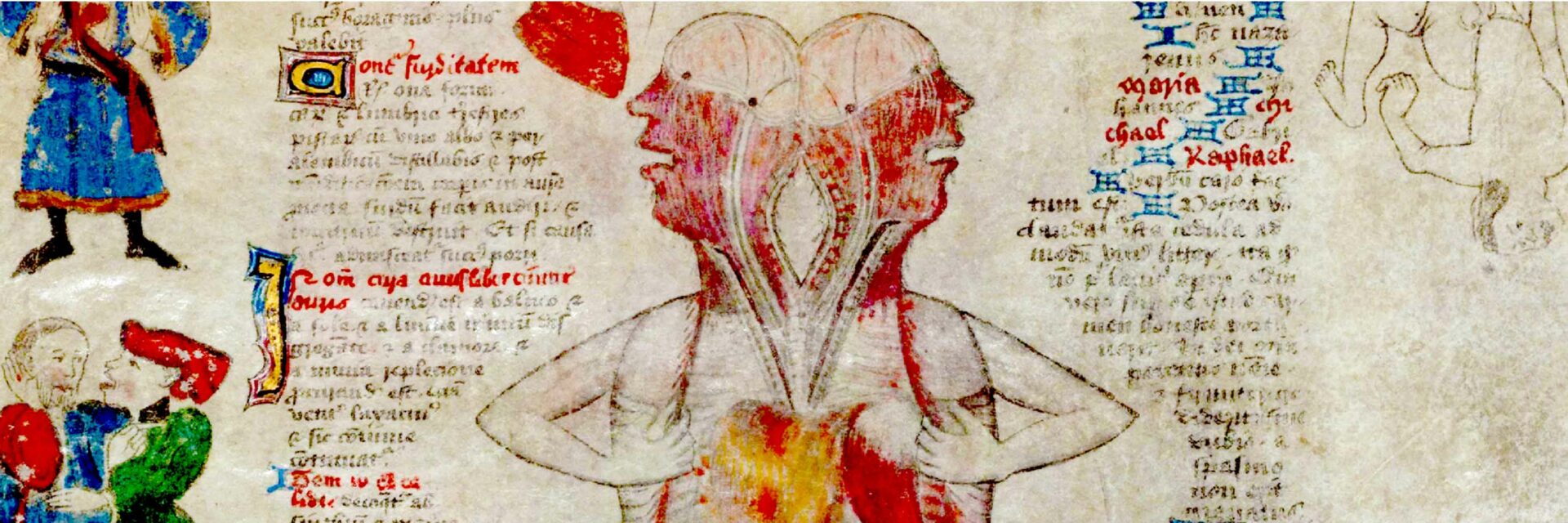

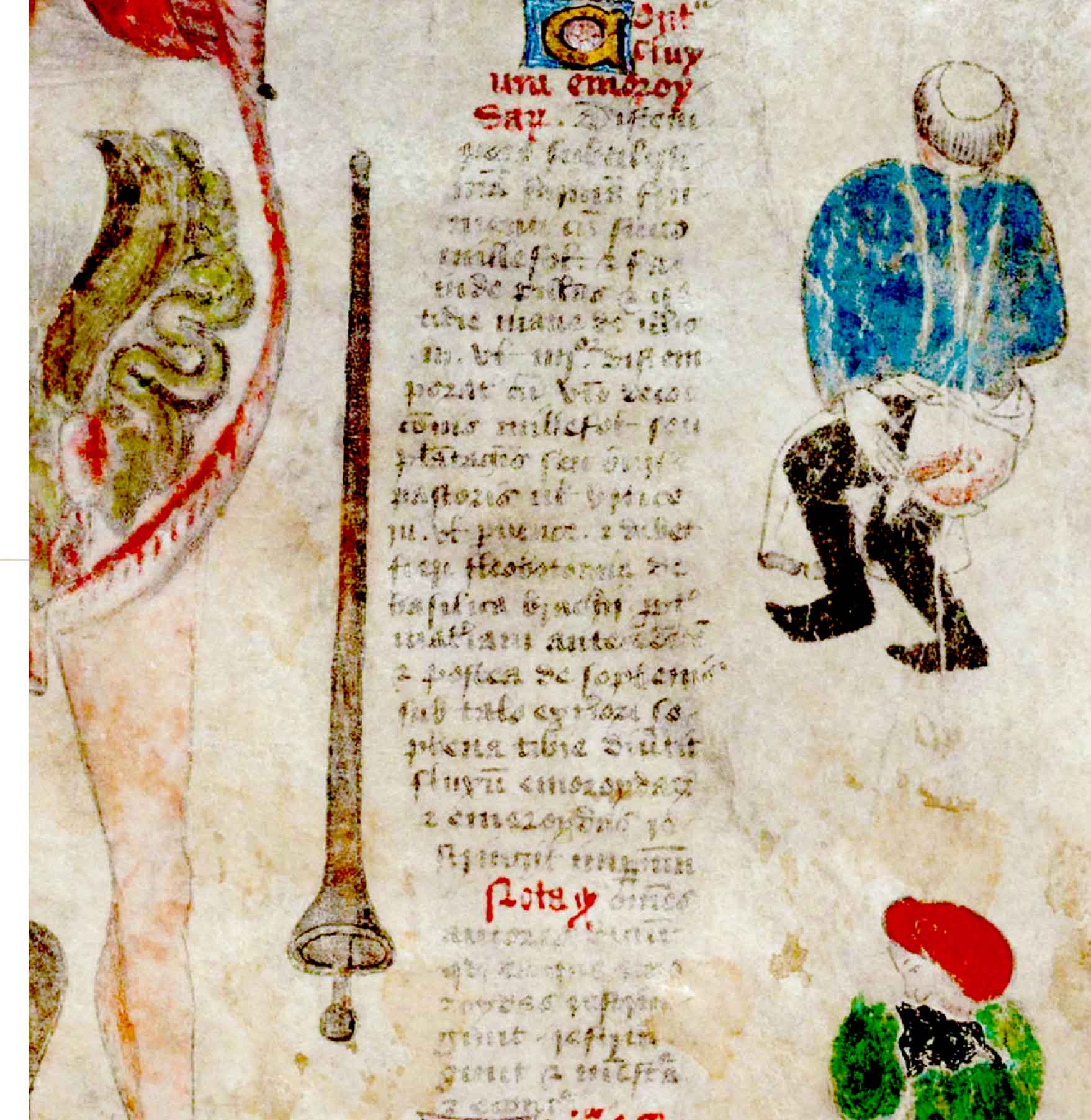

During the 13th century, the Latin term cancer began to be placed within a more specific taxonomy. Physicians and surgeons, particularly those who belonged to the Schola Medica Salernitana, started making distinctions based on more empirical criteria, also defining subspecies according to the stages of development or the area of occurrence on the body, reconsidering what the old medical authorities wrote.

For example, in the mid-13th century, Roland of Parma, Roger Frugard’s pupil, described in his Chirurgia—a commentary and reworking of his master’s work—an initial phase of cancer called nigrosis or sclirosis, which then progressed into “gangrene with the onset of corrosion”, followed by cancroma or carcinoma, and finally became cancer. Furthermore, he correlated three subspecies of cancer with the location where symptoms appeared, naming them: noli me tangere (“do not touch me”) for the face, zona (“belt”) for the central part of the body (later renamed cingulus, also known as St. Anthony’s Fire), and lupus (“wolf”) on the legs:

At first, it is called sclirosis or nigrosis; when it begins to corrode, it is called cancrena, and finally, it is called cancroma. It is also called noli me tangere when it occurs on the face and should not be touched by the hand, because the fleshy part of the fingers is naturally moist, since it generally contains moisture derived from the humoral juice originating in the liver; and since this disease arises from moisture, when it is located in a moist place it is incurable. In the middle of the body, it is called cincillum corporis […]. On the extremities, it is called lupus, and in that case, it is incurable because the extremities are the most solid parts. [1]

In this passage, beyond providing a very brief description of the stages of cancer, Roland of Parma demonstrates how different types of cancer could change names depending on their location on the body. However, Roland does not explicitly clarify the origin and reasons behind the name lupus,[2] but his accounts of cancer are crucial both to emphasize the fluidity of the term and to contextualize the issue within the medical tradition to which he belonged.

Roland of Parma’s subdivision was not widely adopted within the discipline[3]. In fact, the idea of naming diseases based on their body location was common, though some northern Italian surgeons rejected this approach. One of them was Theodoric Borgognoni, who wrote in his Cyrurgia:

Physicians also distinguish cancer based on the quality of the complexion, stating that cancer and lupus are formed due to a more inflamed bile than noli me tangere. […] In the books of the ancients, there is absolutely nothing regarding such distinctions, as they did not call these ulcers cancer.[4]

Similar interpretations also come later from Bruno of Longobucco:

Cancer, however, is distinguished by the masters according to the diversity of its species, because, as they wish, one is called noli me tangere and another lupus. […] However, I, Brunus Longoburgensis, do not presume to assert any truth regarding this distinction, as I have found no trace of it in the books of the ancients. [5]

From the thirteenth century onward, however, the term cancer also appears in certain religious texts in association with a different disease, morbus regius. In the Middle Ages, morbus regius referred to scrofula, a condition whose meaning itself changed over the centuries, being synonymous with jaundice in antiquity and the Renaissance and later becoming known as “the disease cured by the royal touch”.[6]

As it can be seen, Theodoric Borgognoni and Bruno of Longobucco did not share the view of those who assigned different names to cancer based on its location, particularly concerning noli me tangere and lupus. However, the central issue of the debate was not whether these conditions were observed and recognized on the basis of their symptomatology, but whether they were to be classified on the basis of their cause of onset: that is, whether they were to be understood as the same disease called cancer in different parts of the body, as different stages or manifestations of it, or instead as entirely distinct conditions, such as ulcers.

The perspective was overturned by the French surgeon Guy de Chauliac, who in his Chirurgia magna (1363) states:

The species and differences of cancer are derived from three elements: the nature of the disease, the matter from which it originates, and the nature of the tissues involved. Concerning the first, it is said that some types of cancer are mild, small, and not very painful; others are large, aggressive, and cause intense pain. Regarding the second, it is said that some types originate from black bile “burned” in itself [simple], while others arise from black bile “burned” together with other humors, especially “burned” yellow bile [composite]. For the third, it is said that some develop in simple tissues such as flesh, veins, nerves, and bones, while others in complex tissues, such as the face, where it is commonly called noli me tangere; in the flanks, lupus; and in the central part of the body, cingulus, as Rogerio claimed, in contrast to Bruno and Theodoric, who held that none of the ancients ever referred to it in this way. [7]

This crucial passage from Guy de Chauliac’s Chirurgia Magna is found in the section dedicated to cancer ulcerosus. After reviewing all the elements from which cancer could originate, as he did with apostemata, and reiterating the difference between simple and composite cancri, he confirms that there is indeed a type of cancer classified based on its body location, citing noli me tangere, cingulus, and lupus, as previously mentioned by Roger (and Roland of Parma). In doing so, he criticizes the Italian surgeons Theodoric Borgognoni and Bruno of Longobucco for failing to acknowledge this classification due to its absence in ancient texts. Moreover, Guy de Chauliac differentiates lupus from another condition called herpes esthiomenus:

Claudio Zabatta holds a Master’s degree in Historical Sciences from the University of Bologna. His research focuses on the evolution of the concept of cancer in relation to black bile within humoral theory between the Middle Ages and early modern period. For his master’s thesis, he studied surgeons of the rational surgery tradition, who between the 13th and 14th centuries emphasized practical medicine over theoretical approaches. For his future PhD, he plans to explore how cancer’s classification and treatment evolved through alchemical and early chemical practices, focusing on changes in the concept of black bile within humoral theory during the early modern period.

Esthiomenus, though not strictly a pustule, is nevertheless the result of pustules, and its treatment corresponds to them. It leads to the death and dissolution of a member, and for this reason, it is called esthiomenus, almost meaning “the enemy of man”, involving putrefaction and softening, unlike lupus and cancer, which dissolve the tissue through corrosion and hardening. Thus, they are not the same, as claimed by Theodoric, Lanfranc, and Henry.

Esthiomenus is commonly called St. Anthony’s Fire or St. Martial’s Fire. The Greeks referred to it as cancrena, as Galen states in De tumoribus praeter naturam. Avicenna further distinguishes the two based on the severity of tissue destruction. [8]

In this passage, Guy de Chauliac highlights the distinction between lupus and esthiomenus, focusing on how they affect the limb. While lupus destroys the body by corroding it, esthiomenus gradually decomposes it, leading to severe infections similar to gangrene. The author refers to this condition as gangrene, as described in Greek texts and also found in Galen’s De tumoribus praeter naturam. However, as with many other terms associated with cancer, there is considerable terminological overlap. Previously, Lanfranc, in his Practica, had considered “shingles” (or the “fire of Saint Anthony”) as a variation of the term cancer used by the Lombards. More specifically, Roger of Parma had linked it to the so-called cingulus, a form of cancer that appears in the central part of the body, particularly around the waist. What is interesting here is that the term lupus appears in all these descriptions, interpreted as a variant of shingles. With Guy de Chauliac, however, we encounter a third disease, which many others had associated with lupus, but which, according to the French surgeon, was a different type of affliction with a more lacerating onset. In support of this, as with other sections of his work, he cites two major authorities that medieval doctors and surgeons commonly referred to Galen and Avicenna.

The reflections on this disease were strongly influenced by metaphor, especially at the popular level, due both to the fear of the animal and the aura of mystery surrounding it. Guy de Chauliac was the first to report the common people’s beliefs, who considered lupus as a ferocious beast that devoured the flesh of those afflicted. They thought that eating chickens could be a remedy, because, if nothing else was available, the animal would resort to eating people.[9] He states:

Many reduce their virulence and voracity with the application of a red cloth and the use of chickens. That is why the people say it is called lupus because every day it “eats” a hen, and if it does not have one, it ‘would eat’ a person. However, these treatments are mild, and if they do not do good, they certainly cannot do much harm. [10]

The reflections on this disease were strongly influenced by metaphor, especially at the popular level, due both to the fear of the animal and the aura of mystery surrounding it. Guy de Chauliac was the first to report the common people’s beliefs, who considered lupus as a ferocious beast that devoured the flesh of those afflicted. They thought that eating chicken could be a remedy, because, if nothing else was available, the animal would resort to eating people.[9] He states:

This passage appears in the section dedicated to palliative care of his Chirurgia magna, and despite being aware that this remedy was a popular belief not based on medical science, he still mentions it, considering it a mild treatment that would cause no harm to the patient at most.

However, due to a certain lexical proximity, lupus was sometimes confused with another disease characterized by subcutaneous swelling, known as lupia, particularly in the Italian Peninsula. This disease was classified under the category of “phlegmatic apostema”, which also included scrofula.[11] Among the rational surgeons who mention it is William of Saliceto, who refers to it in his Chirurgia and links it with herpes esthiomenus, a condition commonly associated with lupus.[12]

Furthermore, like remedies for lupus, the term lupia was generally known outside medical contexts in the Middle Ages. In Bernard de Gordon’s Lilium medicinae, it was referred to as lupin, the name used for the lupine plant, and likely due to the similarity to pustules, the plant’s name may have also been used as an alternative to the medical term lupia.[13]

Bringing up a fragment of the history of the term lupus is important to exemplify and understand the nosological difficulties associated with a medicine that lacked firm foundations, relying solely on ancient and early medieval authorities whose knowledge was based on personal observations and assumptions. The case of lupus demonstrates how, over the centuries, the name of a disease, while remaining the same, could refer to different types of pathological manifestations, or how the name of the same condition could change over time.

Behind these lexical variations, in addition to simple differing interpretations by doctors influenced by cultural factors, there may have been challenges related to the translation processes from late antique Latin to Arabic and vernacular languages such as Italian and French.[14]

References

[1] Roland of Parma, Cyrurgia, fol. 150va; Luke Demaitre, “Medieval Notion of Cancer: Malignancy and Metaphor”, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 1998: 616.

[2] Alessandra Foscati, 2023, “Dicitur Lupus, quia, in die comedit unam galliam. Beyond the Metaphor: Lupus Disease between the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period”, Mediterranea. International Journal on the Transfer of Knowledge, 8/28:27-53. Available open access at: https://doi.org/10.21071/mijtk.v8i.14304.

[3] Luke Demaitre – Demaitre, “Medieval Notion of Cancer”, 616 – reports having encountered it only in an anonymous 15th-century text on the Glosse in Joannitii Isagoge ad Tegni, British Library MS Royal 12.D.XIII, fol. 116Rb, with the following words:: “Cancer dicitur vel a forma antequam corrodat vel a motu quando corrodit”.

[4] Theodoric, Cyrurgia, fol. 126rb-va; ibidem.

[5] Bruno da Longoburgo, Cyrurgia magna 1252 (with Lanfranc, Venice: 1498; Chirurgia magna et minor in NLM 48-51), fol. 90ra; ibidem.

[6] Foscati, “Dicitur Lupus”, 39.

[7] Guy de Chauliac, Chirurgia magna in Michael McVaugh (ed.). 1997. Inventarium sive Chirurgica magna (Leiden: Brill), Vol. 1, 224.

[8] McVaugh, Inventarium, 75.

[9] Foscati, “Dicitur Lupus”, 47.

[10] McVaugh, Inventarium, 226.

[11] Foscati, “Dicitur Lupus”, 43.

[12] Ibid., 36.

[13] Ibid., 45

[14] Ibid., 45-47.