Early Modern Thaumaturgical Practices

FORMA FLUENS

Histories of the Microcosm

Thaumaturgical Practices

Medicine and Miraculous Healings

in Early Modern Sicily

Marco Papasidero

University of Palermo

The link between thaumaturgy and medicine runs deep through history and dates back to late antiquity, when the veneration of martyrs’ tombs began to take on a curative dimension.[1] From the 12th century onward, and especially in the early modern period, the thaumaturgical element became an integral part of the process of canonisation, serving as an indispensable criterion for the candidate’s inclusion in the list of saints and for their veneration.[2]

Hagiographic texts often mention and describe illnesses, sometimes alluding to the unsuccessful efforts of doctors to cure them. In this article, I present one of these cases, the canonisation process that took into account the miracles attributed to Saint Angelo of Jerusalem – later known as Saint Angelo of Licata or Sicily– that occurred several centuries after his death.

The primary documentation regarding his life, Vita sancti Angeli penned by Enoch, traces back to the 15th century likely originating from the Sicilian region.[3]

As per historical tradition, Angelo was the offspring of Jewish progenitors who subsequently embraced Christianity. Along with his sibling, he affiliated himself with the Carmelite order, thereafter dedicating a phase to ascetic seclusion in the desert. While historical records from Rome present an apocryphal narrative of his purported interaction with the progenitors of two distinct mendicant orders, Saint Francis and Saint Dominic, the veracity of this account remains contested. Progressing through his sojourns in Sicily, he ultimately made his way to Licata. Here, his preaching clashed with a local lord named Berengario della Pulcella, who was engaged in an incestuous relationship with his sister. Allegedly, it was in the church of Saints Philip and James in Licata that Angelo was fatally stabbed in 1220.[4]

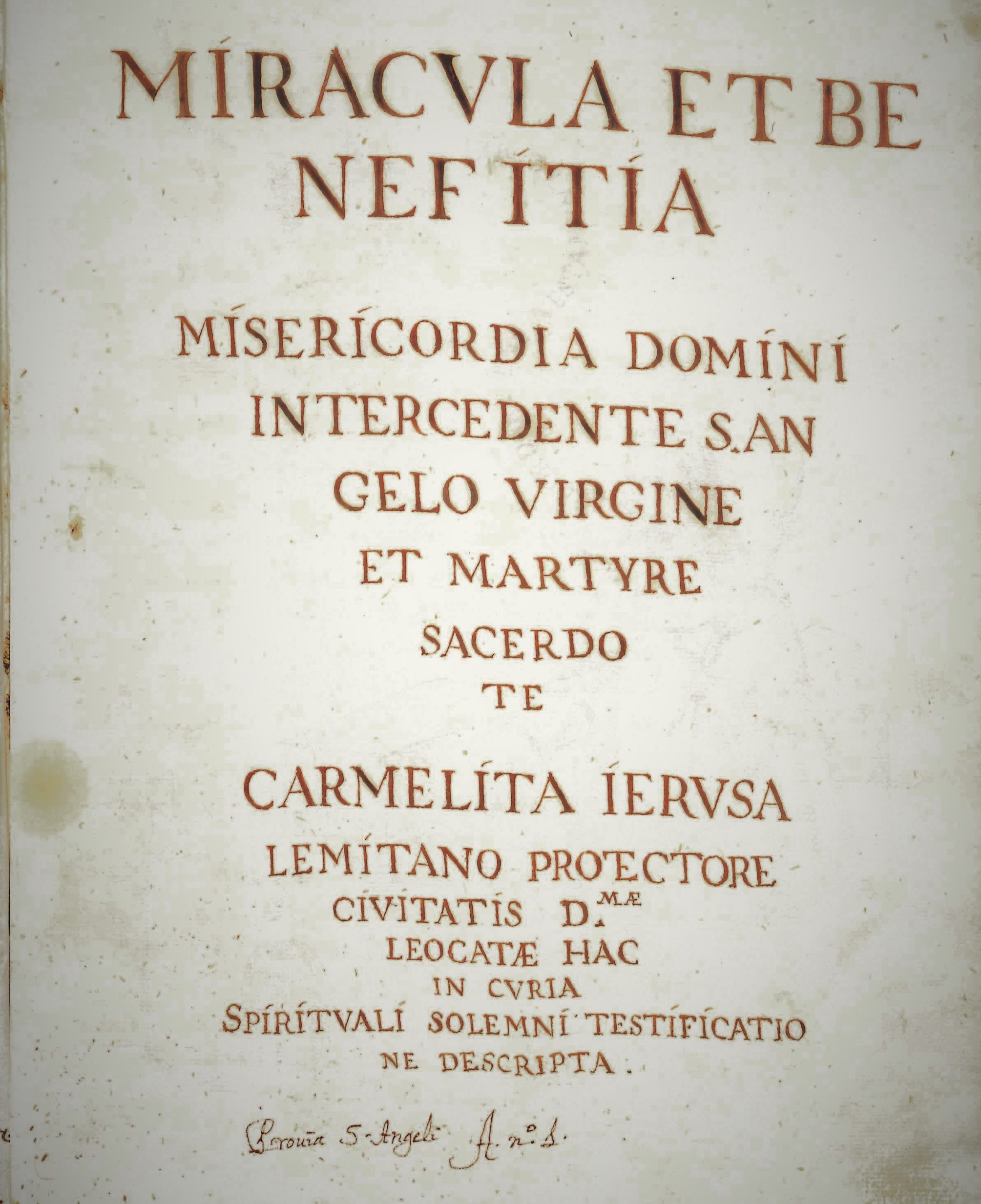

While the particulars of Angelo’s life remain somewhat ambiguous and may offer limited utility in reconstructing his historical character, the text Miracula et benefitia (i.e. ‘Miracles and Graces’) is of notable significance. This work, compiled by notary Iacopo Murci, presents a thorough examination, comprising 113 testimonies, that delve into the miracles attributed to Saint Angelo. This investigation took place between 1625 and 1627,[5] facilitated under the sanction of the Bishop of Agrigento.

In the proceedings, an extensive range of testimonies are present, each detailing the variety of ailments experienced by individuals. These maladies ranged from tertian and quartan fevers, musculoskeletal issues, broken legs, injuries from altercations or occupational hazards, contusions, ocular infections, inflammations, and epilepsy, to complications during parturition. Particularly noteworthy among these is the condition of hernia, colloquially known as rottura in Sicilian dialect, and occasionally termed guallara. This ailment predominantly affected young children, focusing primarily on the genital region, locally termed as bottoni.

The testimonies delineate two principal medical interventions: a significant number opted for a herniary belt (bracale) to manage the hernia. Alternatively, some underwent surgical interventions by barber surgeons. However, this surgical recourse was viewed with trepidation, particularly for young patients, given its associated apprehension and potential risks such as scarring.

Many in Licata sought Saint Angelo as a curative agent for this troubling condition. For instance, one child’s severe hernia was so pronounced that, as delineated by a witness, the child occasionally had to be inverted to reposition the intestine. In another circumstance, the only seeming solution for another child was surgery. Yet, due to the youth of the child, the father hesitated and instead invoked the intercession of the saint, applying water from the saint’s martyrdom site to the affected region. [6]

Another significant facet relates to St. Angelo’s chapel, housed within his church. This sacred space harbored a silver urn, refurbished in the early 17th century to supplant its predecessor. As such, the chapel emerged as the central locus of veneration, decorated with ex-votos, a substantial portion being represented by hernia belts. In a specific instance, with the endorsement of the overseeing Carmelite friars, a father replaced his child’s unsuitable hernia belt that led to skin chafing.

Marco Papasidero is a Research Fellow at the University of Palermo. He received his PhD in History from the University of Messina, and then a fellowship at the General Archive of the Carmelite Order in Rome. In 2018, he won the Sangalli Institute Award for Religious History for his PhD thesis, which was published the following year by Firenze University Press. He also authored various volumes, including Miracula et Benefitia. Malattia, taumaturgia e devozione a Licata e in Sicilia nella prima età moderna (2021, Edizioni Carmelitane). From 2019 to 2023 he was a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Turin in the ERC project NeMoSanctI as well as temporary professor (2019/2020) in History of Ancient and Medieval Christianity at the University of Padua. In October 2022, was also awarded a Research Fellowship at the Edward Worth Library in Dublin.

Another ailment recurrent in hagiographic accounts, especially in canonization or miracle trials, is demonic possession. Manifestations of this affliction often include delirium, convulsions, involuntary physical actions, aggressive behavior, and occasionally paralysis combined with fevers. [7] A particular instance involved a young boy from Licata who suddenly manifested paralysis and lost his speech capacity. Initially consulting a physician, his parents eventually inferred a potential possession based on the sudden onset and unconventional nature of his symptoms, thereby seeking the saint’s intervention.

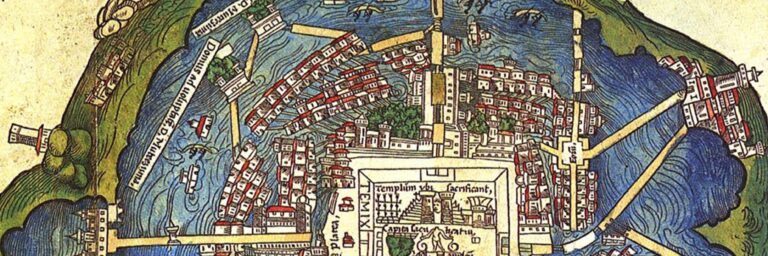

Licata’s Church of Sts. James and Philip holds historical prominence as the martyrdom site of the Carmelite saint in 1220. Subsequent to this event, the local populace revered his relics. Furthermore, hagiographical accounts posit that a spring miraculously emerged at the very spot where his remains were placed.

This spring’s water, according to trial data, was available for consumption either freely or under Carmelite supervision. The water was even packaged and disseminated by the University of Licata, the municipal entity, for those wishing to transport it to other locales like Malta, Spain, and Sardinia via ships docked at the harbor. The miraculous water served diverse therapeutic purposes: consumed primarily for internal disorders or fevers, or applied externally, including as baths, for dermal conditions. Historical records also corroborate the therapeutic use of oil from the lamp illuminating the saint’s tomb, a tradition tracing back to late antiquity. Furthermore, the wooden casket believed to house the saint’s relics, possibly from the 15th century, was disassembled and its fragments disseminated. These fragments, varying in size, were either ingested or applied to afflicted regions.

In 1624, a grievous plague emanated from Palermo, claiming numerous lives, including the Viceroy of the island, Emanuele Filiberto di Savoia. His successor, Cardinal Giannettino Doria, faced the contagion’s spread to Licata by May/June 1625.[8] The symptomatic presentation of this plague encompassed dizziness, lethargy, fever, joint discomfort, vomiting, and distinctive swellings or bombone, especially localized to glands, armpits, neck, and groin regions.

Agostino Infrigola, a renowned medical practitioner from Licata, played a pivotal role. Gleaning medical insights from his travels, especially in plague-ridden regions like Barbary and Algiers, he altruistically entered Licata’s quarantine zone to tend to the afflicted. [9]

Physicians, as evident from depositions, were recurrently referenced, with some offering their personal testimonies. Some even endorsed or administered the miraculous water or applied oil from the saint’s lamp. During urn processions bearing relics, doctors were entrusted with verifying patients’ recovery. The physicians’ role was accentuated during the plague’s outbreak. Francesco Perconti, a Licata-based physician, concealed his onset of symptoms. Fully cognizant of the associated risks, he appealed to the saint, applying a relic fragment where the plague symptoms manifested.

The miracle trial of Saint Angelo in Licata presents an invaluable repository for studying the intersection of thaumaturgy and medicine. Its insights are further enriched when juxtaposed with analogous contemporary sources from the region, offering profound understandings of both popular thaumaturgy and the historical trajectory of medicine.