Medical Notes on Agresto

FORMA FLUENS

Histories of the Microcosm

Medical Notes on Agresto

Giovanna Zipoli

University of Florence

Some scholars have recently investigated the value of “Agresto”, a sauce or better a condiment, used for food and therapeutic uses (tam ad ciborum quam ad medicamentorum usum). [1]

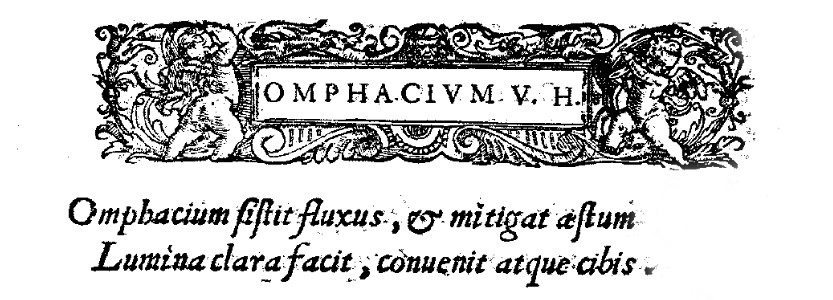

Agresto is an acidic substance obtained from boiling and subsequent pressing of “unripe grapes” (chicchi d’uva mal maturi) to which salt, vinegar, spices and other ingredients were added. It could be “reduced” (i.e. cooked) in the sun. Green fennel and other odoriferous herbs were also added to it. [2] We find it referred to by the Latin omphacium, agrestum (Fig. 1): “the liquor, which is extracted from pressed Agresto, which is then salted, and served as a condiment.” [3] Necessary in the preparation of many dishes (sauces, green blancmange, pies) and an unfailing complement to meat or fish, Agresto was dried in “bullets” (pallottole). In their absence, it was substituted with gooseberry, lemon or “melangole” (i.e., bitter oranges) juice to obtain the sour-spicy-sweet taste that lasted a long time.

Figure 1. Entry on Agresto (Omphacium) in De bonitate et vitio alimentorum centuria by Castore Durante (Pesaro, 1565)

Present as verjiuce in several recipes from the Ménagier de Paris (late 14th cent.) in sauces and victuals, it was almost ubiquitous in Maino de’ Maineri’s 14th-century Opusculum de saporibus, juxtaposed with meats of various kinds and fish. Indeed, all “acrid” substances were believed to be vital to “prohibit putrefaction,” benefit febrile heat and stimulate appetite, as suggested by the physician Giovanni Michele Savonarola in the mid-14th century, who advised cooking meat in acetous substances (caro decocta in acetosis), a widespread practice at the time. Agresto was particularly used with pumpkin cooked over embers, in stewed poultry ‘in guazzetto’, in ‘frittata’ in the oven, with roast pigeons (so Romoli and Artusi), as well as in various “di magro” recipes.

The use of Agresto in medicine and food is documented as far back as the classical world and among the Arabs,[4] and is mainly related to areas where vines were grown; much used in Italian and French cooking. Cold to the third degree and dry to the second – according to the dictates of Galen’s doctrine of the degrees of substances – it was blended with must or wine. Sought-after but perishable, it was stored in barrels; efforts were made to strengthen its preservation.[5] More delicate was the one with gooseberries.

In medieval and Renaissance medicine it was argued that vinegary Agresto was suitable for those of choleric complexion, in that it cooled their spirits, but also for phlegmatic and melancholic complexions because it evacuated “phlegm.” Noteworthy, in this regard, are the suggestions provided by the various Regimina sanitatis and treatises on how to preserve health in times of plague in which Agresto is juxtaposed with vinegar, books on agronomy (i.e. those of De Crescenzi, Carlo Stefano, Tanara, and others…) to converge on lesser-known works. I would also like to highlight to the reader the texts of the 16th-century physicians Pisanelli and Mattioli (the more “constrictive” Agresto is made “of Lambrusca”).

Emphasizing medieval medicine’s need to find a balance between substances to temper an “excess” or over-emphasized characteristic, Terence Scully, notes that vinegary Agresto was an excellent “correction” in the excess of two juices (i.e melancholic and choleric), as was the case in “bianzazevero”(a composite of ginger and Agresto). [6] We find Agresto employed in the Ricettario Fiorentino among the “simples,” cooked in an “earthen or stone pot,” it was combined with other substances in preparations. Bernardo Torni, a physician of Florentine Humanism points out that it is suitable for syncopes and that it benefits epidemic diseases. He dwells on the use of contemporaries to add as much salt to the juice of unripe grapes while boiling, pro condimentis, making it usable throughout the year. He acknowledges its cold and dry temperament, its invigorating effect on the stomach, especially the “relaxed” one (in the case of Agresto without salt), and its benefit to expectant mothers. [7] He writes that it curbs the flow of anger, and prevents vomiting.

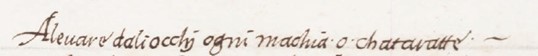

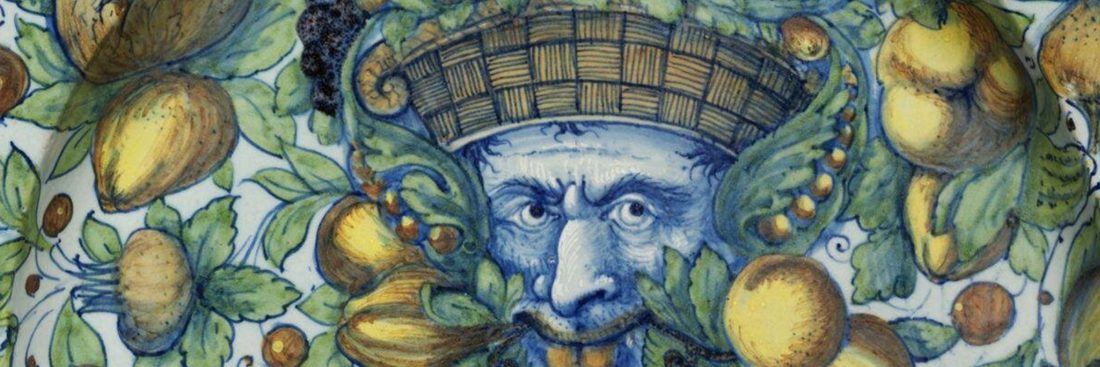

Figure 2. Entry on Agresto in the Libro de i Secretti (Lucca, 1562)

In the sixteenth century, Giovanvittorio Soderini and Davanzati Bostichi address in their treatises on agriculture and vines the production processes, preservation methods and use. In the Libro de i Secretti, e Ricette esposti da frate Giovanni Andrea dell’Ordine dei Gesuati (Lucca, 1562), at least two recipes attest to their use (Fig. 2), which is that to remove from the eyes any stains or cataracts and that of being water to splash over the penis for those who have gonorrhea. [8]

Born in Sesto Fiorentino (Florence), where she lives, Giovanna Zipoli is a retired teacher, graduated in literary subjects at the University of Florence, where she continued her studies in Medieval Archaeology as a postgraduate. She has moved from an interest in the study of containers to that of contents: from ceramics (pottery, albarelli…) to food and ancient medicine in Italy, in the Mediterranean basin and in Europe. In 2005 she founded the cultural association “Arti a tavola-Cultura del convivio” which she is currently the President of. She is the author of two books: Siamo alle frutte (2011) and Il convivio dei Signori (2015), a collection of medieval and renaissance recipes mostly unpublished. Along with Francesco Baldanzi, she has also co-authored the book Il medico fiorentino Bernardo Torni (1452-1497) e gli usi alimentari nella Firenze dei Medici (2020).

The physician and naturalist Castore Durante (1529-1590) gives a comprehensive overview of the medical applications of Agresto in the sixteenth century: “For purulent ears, for certain ulcerations, for ailments of the throat, gums, eyes, etc.”

Agresto being acidic and constrictive ‘perfectly cools, and astricts’. Valuable as a condiment and in medicine because it “stagnates, et constricts,” it serves in all morbi calidi (i.e. hot illnesses), it is also useful in “ardors” when placed on the mouth of the stomach and the flanks. It is put in enemas for dysentery and for women’s flows. It is drunk, watered down, in “fresh sprays “of blood in small quantities; if it is salted, it should not be given to feverish people.

Agresto is useful to the “relaxed stomach that does not digest well; it restores pregnant women who suffer from fainting and colicky pains.” In food it is useful in times of plague; a syrup is made from it for thirst in the summer season.[9]

“It is a common and trite thing to say how Agresto is made in Tuscany”. Thus the Dominican friar Del Riccio who documents, at the end of the 16th century, the production, “pleasantness” (i.e. making the grapes remain small and unripe in a “buffone,” or glass jar), uses and benefits of Agresto. He argues that cooks (“cucinai”) need Agresto and vinegar or similar juices:

which make the food tasty and good and bring back the taste to those without appetite and those who eat by custom, when the hour of dining comes, and not because they feel like they have to eat. These are the ones who morning and evening are in banquets, like so many gluttons [… ] and then they attend physicians often because those who eat much and without any want have need of many purgatives and medicines all the year round, and they cannot do other than have around them apothecaries physicians. And so they always keep themselves sick, by reason of their crapula, and, as the proverb says, more kills the throat than does the knife. […]

Thus, Agresto admirably helps during the summer, to mitigate the heat, awaken the appetite, and to those who are of hot complexion and gallant stomach. It should be used in the summer and in hot weather: and it is good for the young and choleric: but it is the enemy of the old and phlegmatic. I say this Agresto to be cold in the first degree, and dry in the second. This being used together with roasted and boiled meats, or in other fatty foods and victuals, it is good but one should always use it moderately. Agresto sauce is far more delightful in eating than vinegar and is also healthier. It is used not only in foods but also in medicines, as Dioscorides and other experienced men say.[10]

French chemist and physician Nicolas Lémery (1645- 1715) recommended Agresto juice mixed with water and sugar to form the so-called “Agresto water,” which was used for cooling and urinating. He himself says it was used more as a delight than as a medicine. It was used for gargling and, mixed with plantain and rose water, in throat inflammations. It cleanses the face, used with “linen cloth,” removing red spots and freckles. Lémery indicates preparations with Agresto juxtaposed with other “matters” such as Rob Mororum seu Diamorum compositum, with the juice of domestic blackberries, cooked with honey and sapa and with the addition of myrrh and saffron; it is good for “cleansing the phlegmas of the chest, to facilitate respiration”; he also indicates Agresto syrup, “refreshing,” against vomiting and to stimulate appetite.

To make use of it nowadays, it should also be revived in the “basic” version as an alternative to tomato paste. It could also be made more palatable with the addition of must or sugar, or soured with vinegar, which gives Agresto a different colour and flavour according to the grapes used from area to area, thus having a wider use.