Honey in Coptic Medicine

FORMA FLUENS

Histories of the Microcosm

Honey in Coptic Medicine

Traditions and Uses

Mona Hassan Ahmed Sawy

Assiut University

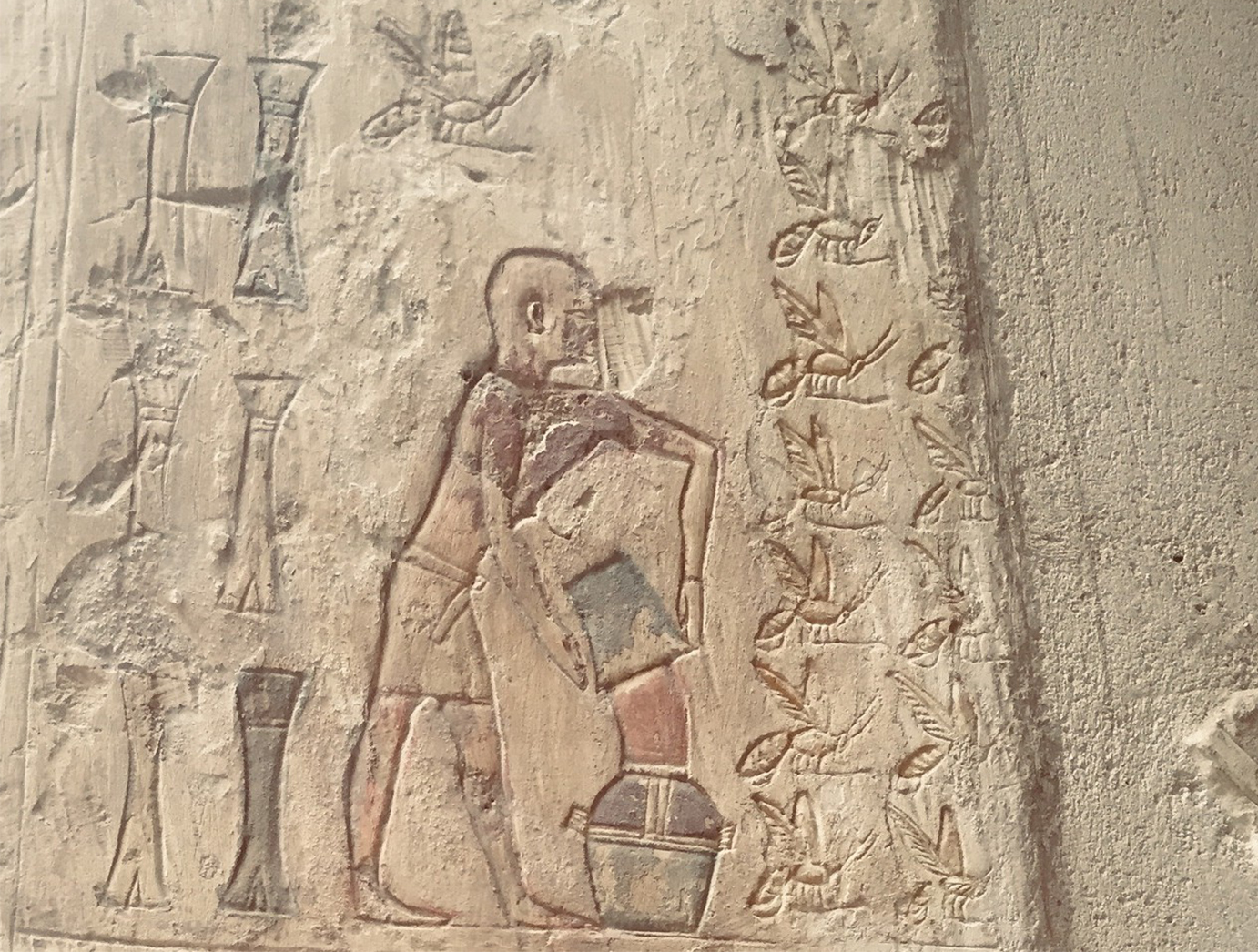

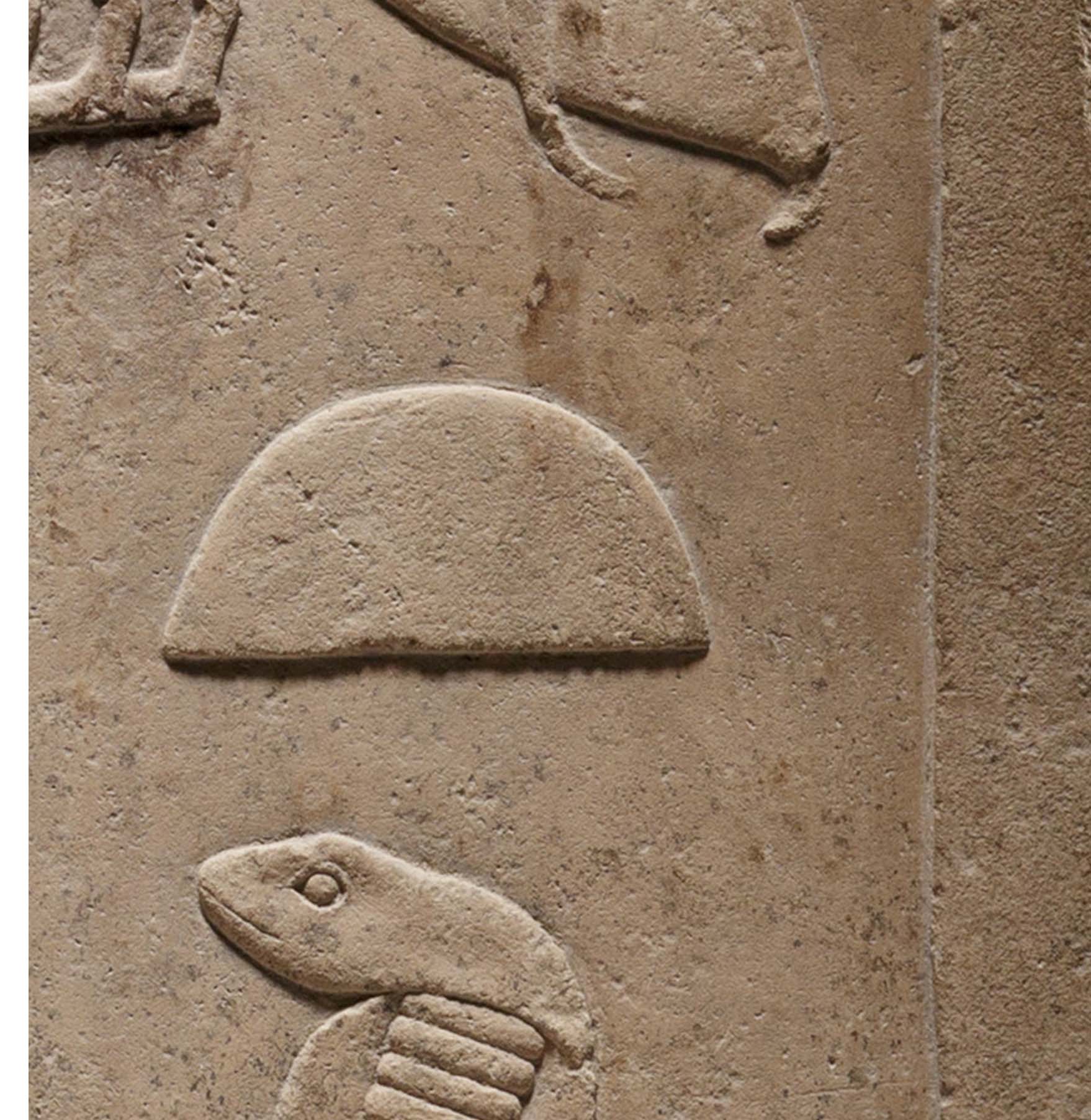

Bee honey (Apis mellifera) is one of the most cherished and valuable natural substances, in constant use from prehistoric times to the present day. The use of honey has a very long history; in the dynastic period, it was considered the “tears of the sun god” and was appreciated for its nutritional and medicinal properties.

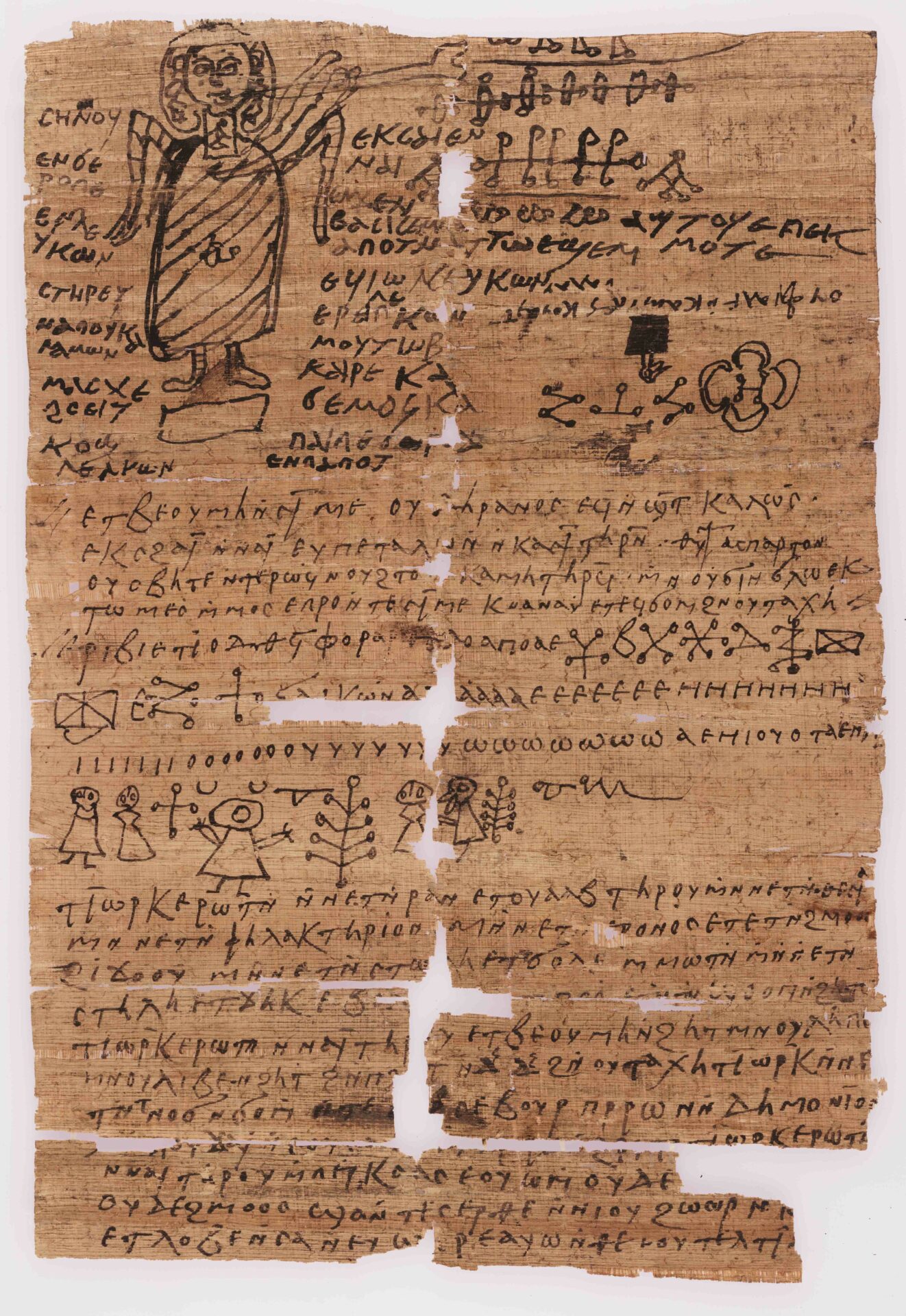

Honey has been used for various purposes, including medicine, cooking, and religious rituals. The same uses continued in Byzantine and Late Antique Egypt, as recorded in Coptic texts, which mention honey in food, drinks, and medical remedies [Figures 1-2].

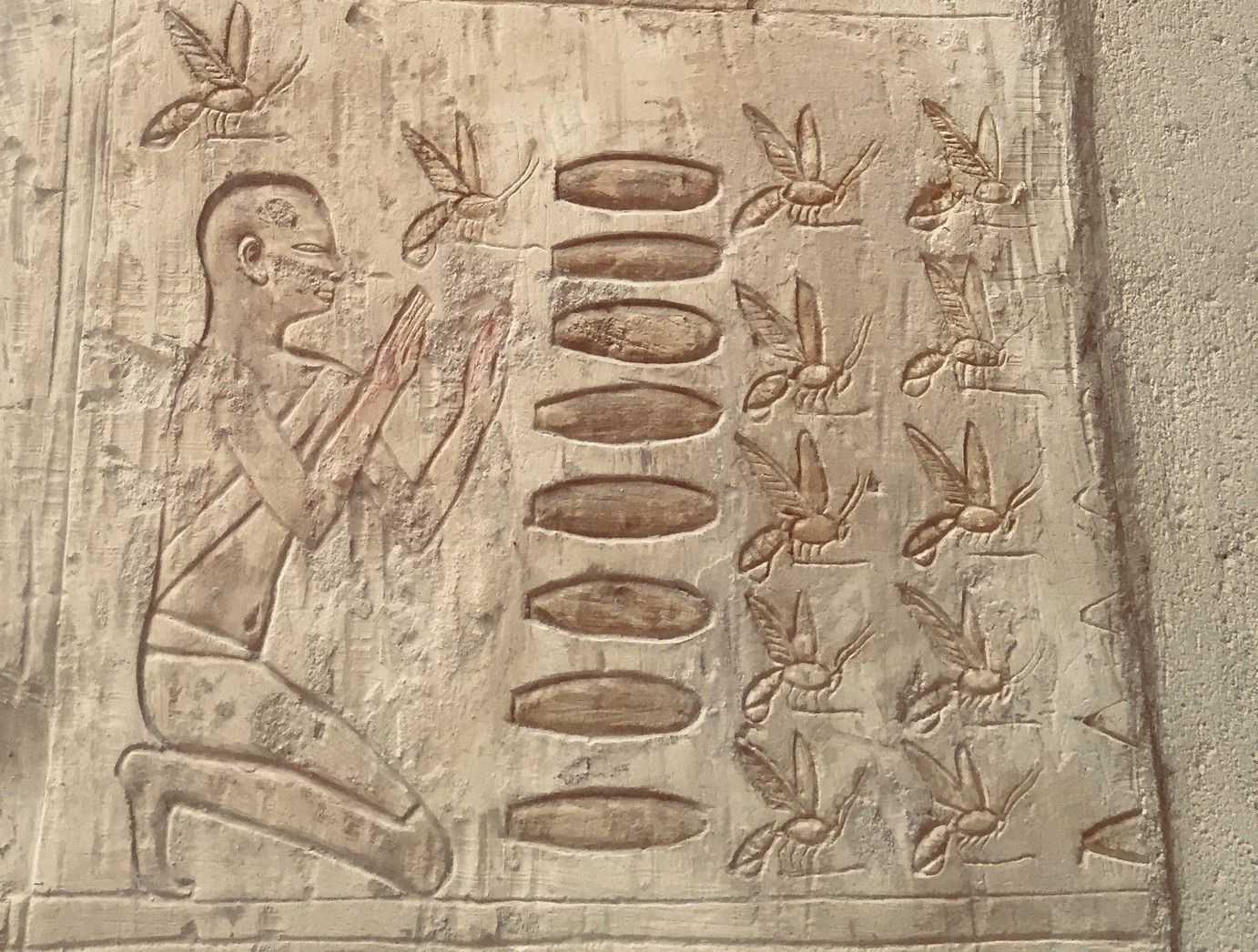

Aristotle, the first scientific beekeeper, introduced honey into scientific study in his Historia animalium. Hippocrates documented its health benefits, including its use in treating pain, thirst, and fevers. In ancient Greek mythology, honey also appeared as an emblem of virginity and fertility. Romans such as Virgil, Varro, Columella, and Pliny the Elder regulated beekeeping and achieved high productivity, variety, and quality. The Old Testament also refers to manna, a different and legendary sweetener said to have descended from the sky in the form of rain on chilly nights in the desert [Figure 3].

Terminology

The native Coptic word for honey is ⲉⲃⲓⲱ (ebiō), and the nominal form ⲉⲃⲓⲉ (ebie)—derived from the Egyptian bj.t (bīty). It corresponds to the Greek word μέλι (méli) and the Arabic عسل (ʿasal). The bee in Coptic is known by ⲁϥⲛⲉⲃⲓⲱ (afnebiō, “honey fly” or “bee”), from Egyptian 3fj n bj.t (ʾafī n bīty)![]() commonly abbreviated to bj.t. Honeycomb in Sahidic Coptic known as ⲙⲟⲩⲗϩ (moulh), and in Bohairic ⲛⲏⲛⲓ (nēni).[1]

commonly abbreviated to bj.t. Honeycomb in Sahidic Coptic known as ⲙⲟⲩⲗϩ (moulh), and in Bohairic ⲛⲏⲛⲓ (nēni).[1]

Types of Honey in the Coptic Tradition

The Coptic texts recorded some different types of honey as follows:

ⲉⲃⲓⲱ ⲛⲁⲧⲙⲟⲟⲩ (ebiō natmoou): “waterless honey,” meaning solid, non-liquid honey, according to Dioscorides.

ⲉⲃⲓⲱ ⲛⲁⲧⲁⲓⲕ (ebiō nataik): “breadless honey.”

ⲉϥⲓⲱ ⲛⲁⲧⲁⲕⲧⲟⲛ (efiō natakton): “Attic honey,” (ⲁⲧⲁⲕⲧⲟⲛ= Greek Ἀττικόν).

ⲉⲃⲓⲱ ⲙⲙⲉ (ebiō mme): “true honey,” meaning “real” or “pure honey”.

ⲉⲃⲓⲱ ⲉⲛϣⲟⲩⲃϯ (ebiō enšoubti) — meaning unclear; Till notes that he does not know its meaning.

ⲉⲃⲓⲉϩⲟⲟⲩⲧ (ebiehōout): “Wild honey”. The term is notable because the Gospels of Mark and Matthew state that John the Baptist ate it. Mark 1:6c Mark 1:6c indicates that, while in the wild, “John was in the habit of eating locusts and wild honey,” and Matt 3:4c claims that his provisions “consisted of” these foods.

Medical Usage of Honey

Ancient Egyptian medical writings contain about 500 recipes referencing honey, used for a variety of purposes. Ptolemaic and Roman recipes also attest to honey’s use in medicine, including oral prescriptions, suppositories, ointments, bandages, incense, and eye remedies.

Honey’s numerous properties have been studied. Because of its acids, “inhibins” (substances that inhibit bacterial growth), and antioxidants, it has an antibacterial effect. Due to the concentrated sugar solution in honey, microbial growth is further inhibited (an effect referred to as osmotic pressure). Its high sugar content also gives it hygroscopic and preservative qualities. Its flavonoids, which are secondary plant compounds with positive health effects, have anti-inflammatory and antispasmodic action in cases of colds. Additionally, honey benefits the cardiovascular and immune systems. However, proper storage is crucial for preserving these active components. Honey is damaged by moisture, heat, and light.

Honey is a common ingredient in medicinal preparations, often used as a taste corrector because of its pleasant and intense flavour. Most recipes do not heat honey, and it is prescribed for internal use in various diseases:[2]

Against Intestinal Worms

Ch[assinat] 110 prescribed a remedy against a specific type of worm called ⲧⲙⲟⲥ ⲛϣⲟⲉⲓϣ (tmos nšoištmos). The recipe recommended three remedies against worms, one of which recommends drinking one cup of purslane, cow’s milk and honey for three days: “Someone who has worms inside him….take purslane, cow’s milk and honey; give a cup to him in three days. Cook them first.

Against Gas in the Stomach

Ch[assinat] 69 prescribes honey for excess gas: “… a stomach heavy with gas, so that it stops blowing: Cumin, pepper, rue, mustard, Arabic natron, honey; crush them well; give him to eat it; he will recover.

Against Testicular Disease

Ch[assinat] 169: “Someone whose testicles are sick permanently: Crush a stack of laurel leaves; shake them in a sieve; mix them with honey; make him drink with hot water.”

Against Pain in the Rectum

Ch[assinat] 226 recommends a specific remedy made from the dung of the wolf. A remedy that is considered a part of medico-magical prescriptions.[3] It read as follows: “The great intestine that has pain: Burnt wolf droppings, crushed with white pepper; knead them with honey, drink it, but take your salary first, it is tested.”

Against Inner Diseases

Ch[assinat] 234 prescribes a remedy for “someone who suffers from any illness in his inner parts”:

“Someone who suffers from any ailment in his inner parts: Myrrh one drachma, gum Arabic five drachmas, acacia four drachmas, costus one drachma, wild rue four drachmas; crush them; knead them with honey; apply to him with warm water.”

Against Vomiting

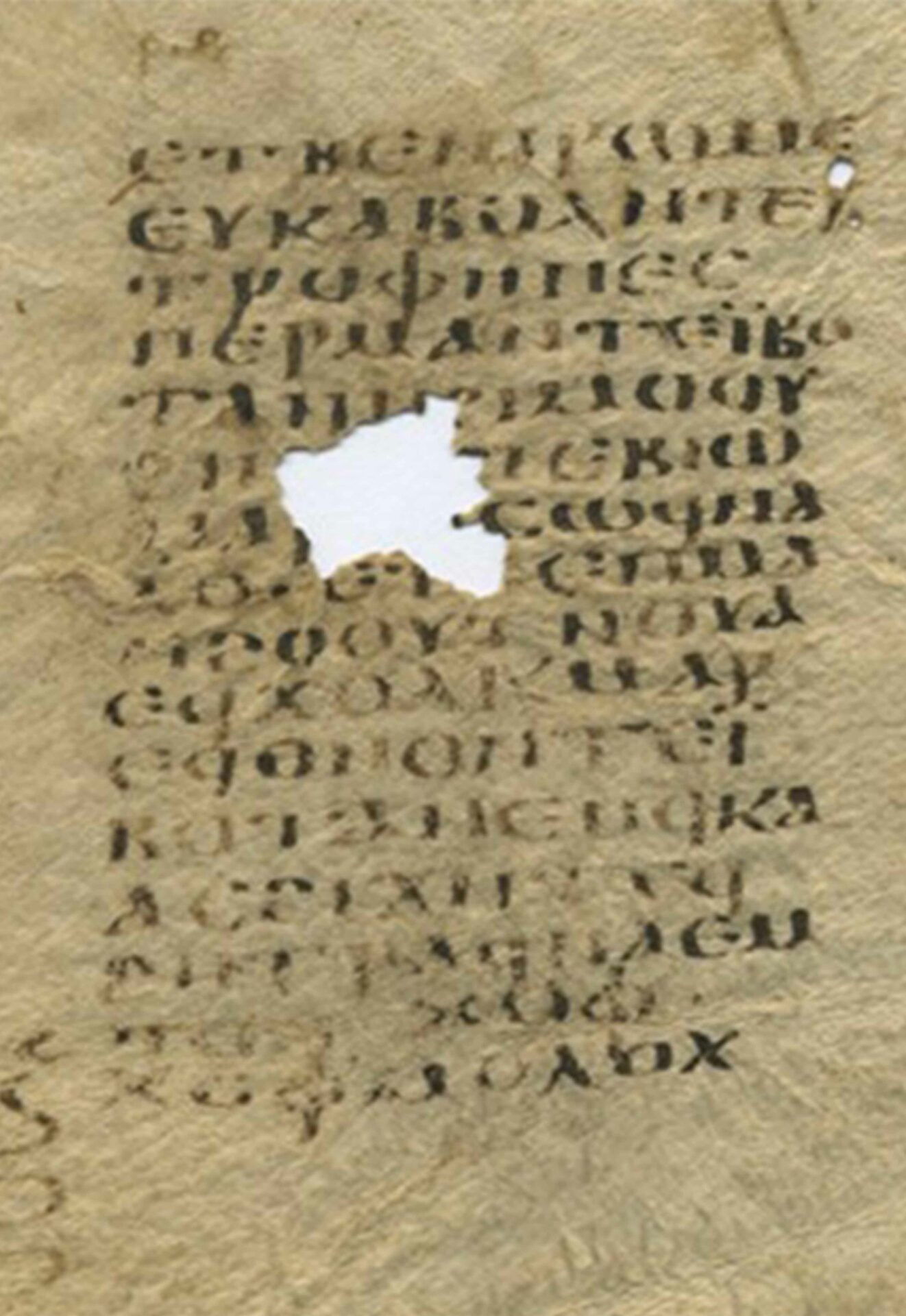

P.Carlsberg 500 [Figure 4] recommends an oral remedy against vomiting: “For persons who vomit their food: The seed of this herb together with water and wine and honey. Let him drink, he will recover.”

Mona Hassan Ahmed Sawy, a specialist in Coptic studies, holds a PhD from George-August University of Göttingen. Her research spans a wide range of topics, including medicine, magic, and religion in Late Antique Egypt and the early Islamic period. She attended and presented at many international conferences, including in Germany, Japan, Spain, the Netherlands, and Belgium. She currently serves as a Lecturer in Coptic language and Ancient Egyptian history in the Faculty of Arts at Assiut University, Egypt.

For Intestine

Ch[assinat] 74 recommends ⲕⲁⲑⲁⲣⲓⲥⲙⲟⲥ “Laxatives” consist of one ounce of pepper, watercress seed, scammony and eight ounces of natron and spurge, which are to be crushed well and mixed with honey.

Ch[assinat] 75 prescribed a drinking remedy ⲧⲥⲱ for the large intestine: ⲟⲩⲧⲥⲱ ⲉⲧⲃⲉ ⲡⲛⲟϭ ⲛ̄ⲙⲁϩ︤ⲧ︦: “A potion to the large intestine”, consists of: myrrh, castoreum, green vitriol, spurge, and honey.

Gums with Gangrene

Ch[assinat] 159: “Someone whose gums have gangrene: Take seven burnt ambrosia branches and honey; use for them.”

Against Eye Diseases

P.Sarga 21, ll. 7-9: “An eye that waters: … of raven’s eye, and water of onions and honey. Apply to [it … a goat’s gall and honey …”

Ch[assinat] 89: “A cataract and a blot in an eye: pigeon droppings; crush them well with honey without water; apply.”

Ch[assinat] 204 and 205 recommend honey as a remedy against eyes that have mist – for treating the darkening of the eye.

Against Cataract

Ch[assinat] 165: “Someone whose eyes have cataract: Gall of ichneumon (?), gall of chicken, honey, hieratic paper ash; apply.”

Honey and Magic

Honey played an essential role in Coptic magical formulae. A great number of magical formulae recommended reciting prayers or spells on honey, such as P. Lond. Copt. 1007/ British Library MS Or. 5899(1), a part of a prayer of exorcism. The prayer contained magical words that invoke the angel Gabriel, to be recited over water, oil, and honey.

P.Mich. MS 136 pp. 2-14, a book of ritual spells for medical purposes, contained a spell for a malignant disease, which recommended using honey and other ingredients. Another recipe recommended honey to be used against sores: “A little fresh fat from a sow: Grind it. Put it on sores that have appeared at the anus, along with real honey.”

In Köln Inv. 20826,[4] honey appeared to be used in the ritual with other power words, which were recommended to be written on the tongue of the person who used the spell for protection.

In addition, honey was recommended to be used in a love spell, Cairo JdE 42573 (p. 3, ll. 1-5): “Desire. Take the gall of the hare and the sweat of your chest and the blood of your big finger and your [semen]. Purify them with Attic (?) honey. On the 14th day of the moon. Semen. Give it to her, fasting.”

Coptic magical texts also contained several ritual analogies to animals, and honey-bees appeared as one of these analogies in a spell for sex and favour, i.e. London Hay 10414a (recto):

that she may be [like] a honey[-bee] seeking [honey], a bitch prowling, a cat going from house to house, a mare going under [sex-]crazed [stallions],” (verso) “At the moment that you will sprinkle yourselves in the dwelling place, and gather for me the entire generation of Adams and all the children of Zoe, as they bring me every gift and every bounty, they must gather before me, all of them, like a honey bee into the mouth of a beehive.[5]

Berlin 8318/ BKU 1 8, a spell for a good singing voice, recommended wild honey to be drunk with other ingredients:

This is the mixture in the chalice: 21 grape seeds; 12 grains of wild mastic, with a little wild honey diluted with a little Tobe water…[6]

Another spell for the same purpose, i.e. a good singing voice, is P.Yale inv.1791, [Figure 5] where the white honey was mentioned with other ingredients: “White honey; white wine; To be water{?). Offer greetings (?) 21 times (?), … 21 times (?). This is the preparation of the chalice.”[7]

London Oriental Manuscript 6794, (a spell to obtain a good singing voice), the text recommends writing the amulets with real honey.[8]

The Coptic hoard of spells Michigan 593 dates back to the 4th-6th centuries CE, lists honey two times within the spell; one to recite the spell on honey 15 times and another to eat the fried hawk’s egg with honey: “You are to recite it seven 15 times over some honey and some liquorice root…. Take a hawk’s egg and fry it, then eat it over the honey, purifying yourself for forty days until its mind appears to you.”[9] The spell contains voces magicae and invocations used for various purposes such as bite of a reptile, fever, swellings, spleen, headache, vertigo, a haemorrhage, for enemies, for protecting the house and sheep, to protect the ships at sea or on the ocean, for desire, evil eyes and for other purposes.

Conclusions

Ancient Egyptians valued bees as a symbol of legitimacy and associated them with various gods. Bees were the only source of honey, and beekeeping began in the Old Kingdom and continued until the Roman Empire. Honey was also associated with religious practices, with priests taking on beekeeper aliases. In post-Pharaonic and Late Antique periods, honey was used in various applications and was a major ingredient in medical prescriptions. Honey is a natural antibacterial, and it is still used these days to prevent wound infections. And it remains one of the most popular methods. It can be used on all types of wounds, including burns, skin grafts, ulcers, and cuts. Honey’s antibacterial properties are due to hydrogen peroxide, a natural byproduct of honey. Honey also contains sugars that provide an energy source for white blood cells, helping them fight infection. Therefore, honey is still used in traditional Egyptian medicine nowadays.