Health and Illness in Mining Communities

FORMA FLUENS

Histories of the Microcosm

'Bergsucht' and Miner’s Chest

Health and Illness in Mining Communities

Sarah Seinitzer

University of Vienna

University of Bologna

Santorio Fellow

Darkness, dripping water, tiny shafts. Mining is widely acknowledged to be a hazardous industry, with its own medical microcosm. It poses risks not only in terms of financial investment but also to the individuals who dedicate their lives to working within the mines and their surrounding environments. Mining communities face numerous dangers, including water infiltration into shafts, the presence of toxic air within the mines, and accidents above and below the ground. Mining and metalworking diseases, known in Latin as morbi metallici, represented the cost associated with an entire industrial sector, already widely recognized in the early modern period.[1]

From the 16th century, natural philosophers, naturalists, and physicians documented these ailments in various forms. Many writers documented their experiences working as physicians within mining communities, using miners’ own vernacular terminology for their illnesses. Medical practitioners were involved in all aspects of mining and metalworking operations from ritual protections of shafts to treating the ill effects of furnaces. To mitigate mining’s negative health impacts, communities built bathhouses and employed medical practitioners. Mining communities recognized the necessity of these services for centuries to ensure their well-being.

Observing Mining and Metalworking

Ancient authors such as Pliny the Elder (23/24–79 CE), Hippocrates (c. 460– c.370 BC), and Galen (129–c.216 CE) already warned about the poisonous effect of metals and their vapour and the morbi metallici, the disease of miners and metalworkers, that they caused.[2] Numerous early modern scholars documented the causes and remedies of work-related conditions. For instance, physicians and humanists travelled to the mining towns to investigate their nature. In their reports, they also described inhabitants of mining sites and their workplaces, shafts, and smelting huts. Observing the impact of mining on life and health, they documented the industry’s effects. Some also wrote about preventing work-related illnesses and maintaining health.

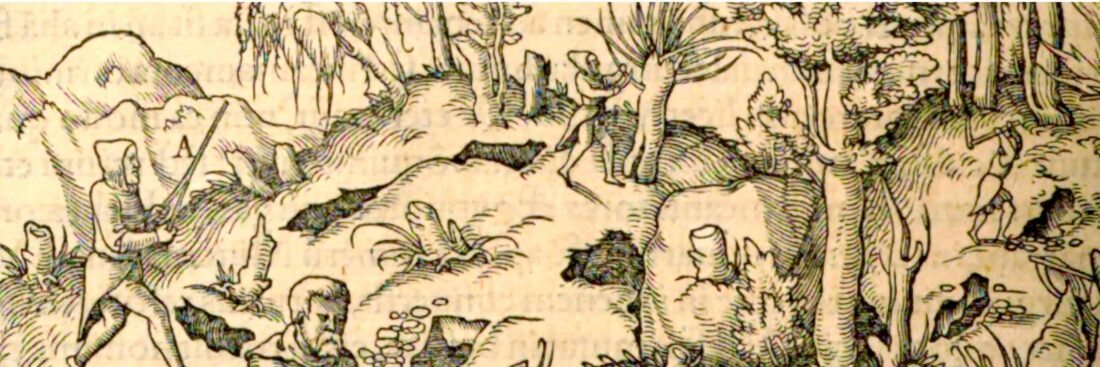

German physician Ulrich Ellenbog’s was one such author. His pamphlet Von den gifftigen Besen Tempffen und Reuchen (“About the Poisonous, Evil Fumes and Smoke”) [Figure 1] is known as the “first work about occupational medicine in the world literature”.[3] Ellenbog himself had little contact with mining, but witnessed the intoxication of metalworkers, in his case goldsmiths, who came to him for medical treatment in the city of Augsburg, where he worked.[4] Written in 1473, this short treatise of only 7 pages was first printed in 1525 and in 1533 in a Bergwerk und Probierbüchlein, a handbook about mining and metalwork. It was reprinted in such mining collections until the 18th century. As the work has a certain importance later on, Ellenbog soon fell into oblivion and was not cited in the subsequent works, either in these Probierbüchlein or by later authors who also wrote about mining diseases.

His pamphlet begins with the effects of coal fumes and mentions its symptoms in case of poisoning. Furthermore, he advises preventing this by opening windows and using incense and wine. Further, he describes the toxicity of lead, mercury and other metals, emphasising that their fumes or vapour are more toxic than the metals themselves. He suggests working outside and to use a cloth to cover their mouths and noses. Beneath that, he recommends remedies, like Bisam (musk) and various herbs. In his suggestions, we can follow the path of combining so-called academic medicine with artisanal medicine.

As Ellenbog was a university-trained physician, his concepts of the human body, but also of health and illness, were derived from the Aristotelian and Galenic system, which was dominant in the late Middle Ages and the Early Modern period. In this system, recommended remedies provide balance in the body. For example, mercury was seen as a cold and moist element, so physicians suggested preventing and treating toxification with garlic, to which hot and dry properties were attributed. In case of toxification, Ellenbog suggested that patients “sweat it out” with the help of baths or beverages with “theriac”, which was already known as an antidote against poisons and venoms. Ultimately, he warned of the vapours of aqua fortis (today known as nitric acid), antimony and verdigris, all ingredients used in the goldsmith’s workshop, which he saw as toxic as mercury and lead.[5]

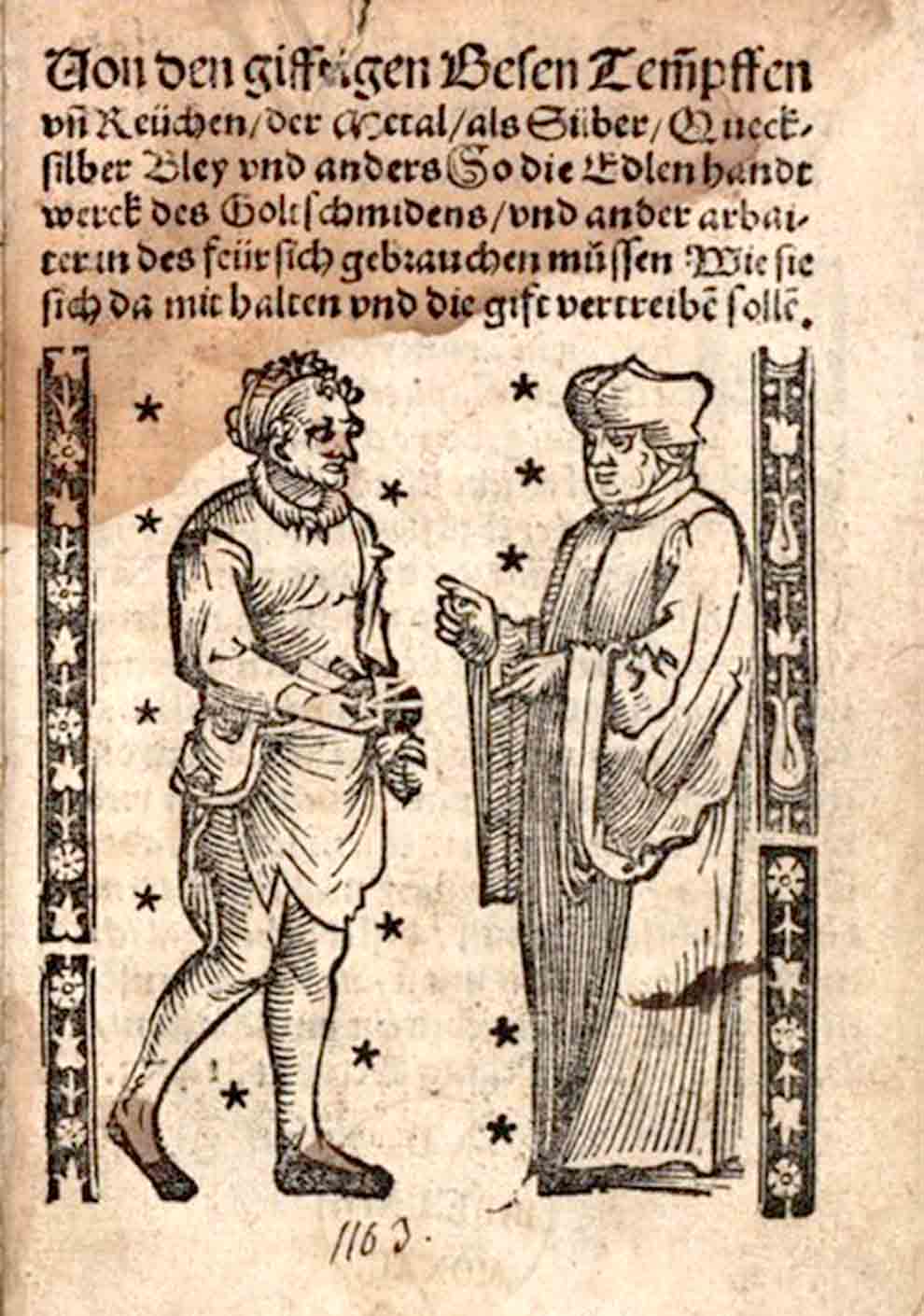

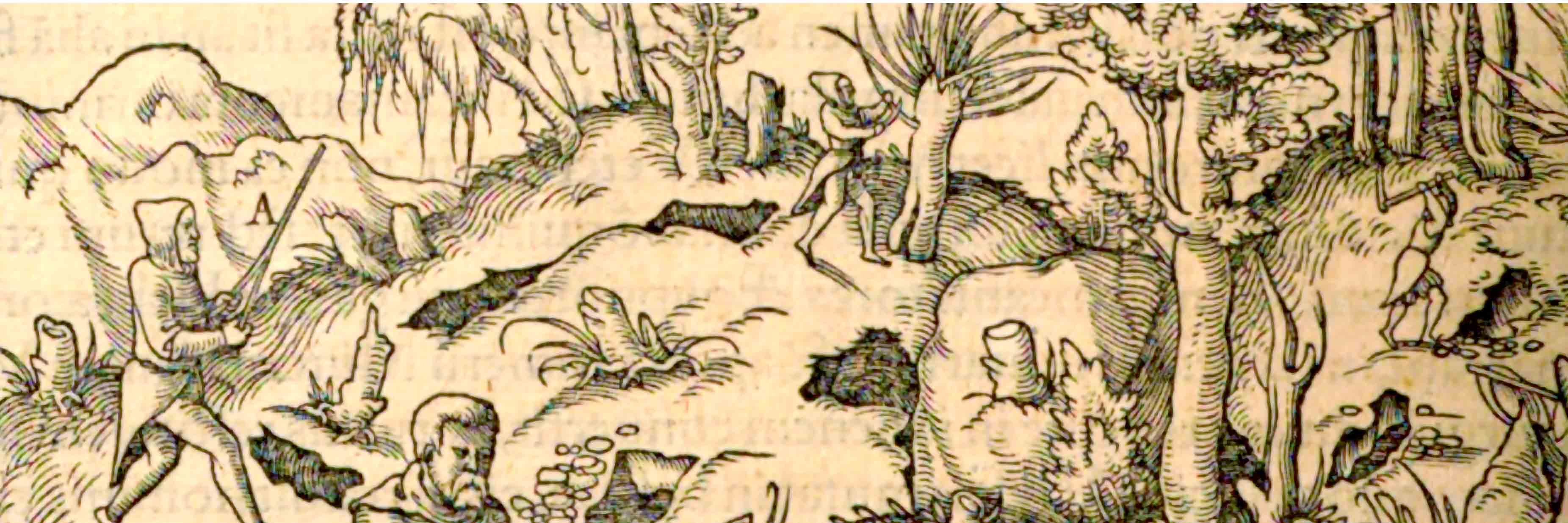

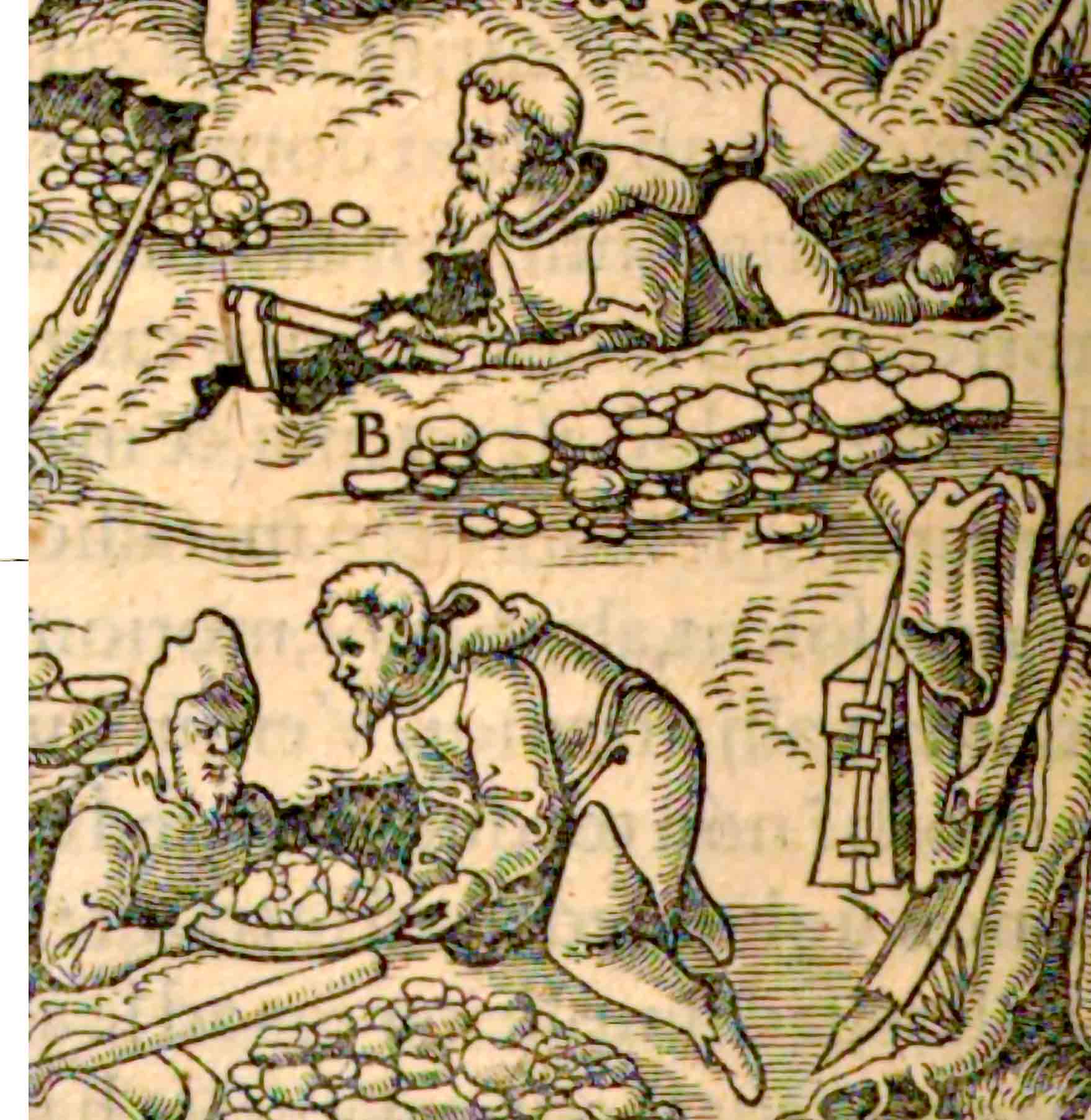

Besides using specific treatments to counteract toxic effects, diet was crucial in mining communities to maintain the balance of the body’s humoral system. Alongside these preventive strategies, wearing protective gear like gloves and masks was essential in reducing the impact of harmful air.[6] In the mining industry, using a mouth cloth was a widespread practice, as noted by several authors. This is also illustrated [Figure 2] by the German mining physician Georg Bauer (1494–1555), who wrote as Agricola, in his 1556 book, De re metallica.[7]Agricola integrated miners’ ailments into the realm of learned Latinate medical knowledge by using the terminology of Hippocratic medicine, yet he did so without applying its aetiological concepts. He used ancient Greek and Latin terms as descriptors of conditions whose causation was attributed to mining dust and its corrosive forms rather than the behavioural, constitutional, or climatic conditions that medical authors adduced to explain respiratory disease. Agricola created a distinct identity and cause for mining-related conditions, which could be described as a broader phenomenon, such as asthma or tabes, that were not linked to mining.

The Swiss physician and alchemist Paracelsus (1493/94–1541) was mainly interested in the health condition of mine workers. Paracelsus’s medical concepts used vernacular knowledge rather than that of the humanists, and in his writing, he adopted the words the mining communities used and implemented them in his medical system.[8]

Sarah Seinitzer is a PhD student at the Universities of Vienna and Bologna as well as a researcher in the ERC STG project Sustained Concerns: Administration of Mineral Resource Extraction in Central Europe, 1550–1850 (SCARCE; Grant nr. 101076422), led by Sebastian Felten, at the University of Vienna. Her research examines the lifecycle of mercury as materia medica. She traces the journey of this toxic metal from its extraction sites in Idrija (nowadays Slovenia) to its use as medical agents in the medical centres of Bologna, Padua, and Venice. She also explores the roles of actors involved in this process, from the health management in mining communities to patients receiving these remedies.

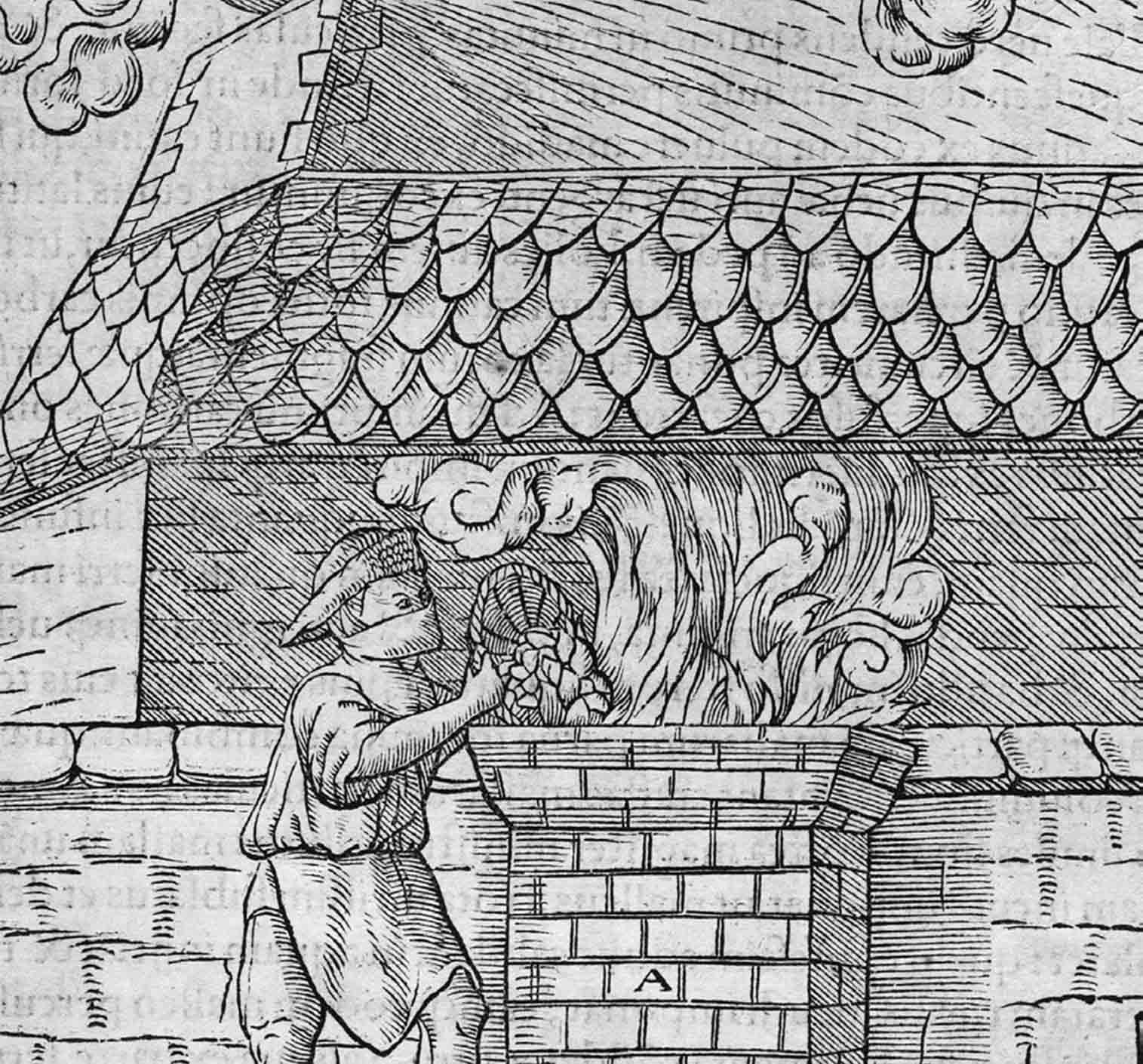

Until the 18th century, medical professionals primarily documented their experiences observed while working in mining areas. During the 18th century, doctors began to write about the specific work-related illnesses faced by mining communities. For instance, the German physician Johann Friedrich Henkel (1678–1744) discussed respiratory diseases he observed as a mining doctor in Freiberg in his medical writing [Figure 3]. [9]

Mining Language and Illness

The specificity of mining diseases is reflected in the distinctive medical vocabulary that emerged from the writings of physicians. Mining terminology, more generally, not only medical terms, attracted interest from early modern scholars who assembled mining dictionaries such as Deutsche Bergwörterbuch (“German Mining Dictionary”) written by Heinrich Veith in the 19th century and produced their own words like Bergsucht, bergfertig and Bergkatze in the German-speaking mining regions. The definitions of these terms reveal that mining communities created their own terms for their microcosm, also including work-related diseases.

Bergsucht (noun f.); bergsüchtig (adj.) = mountain sickness, miner’s sickness

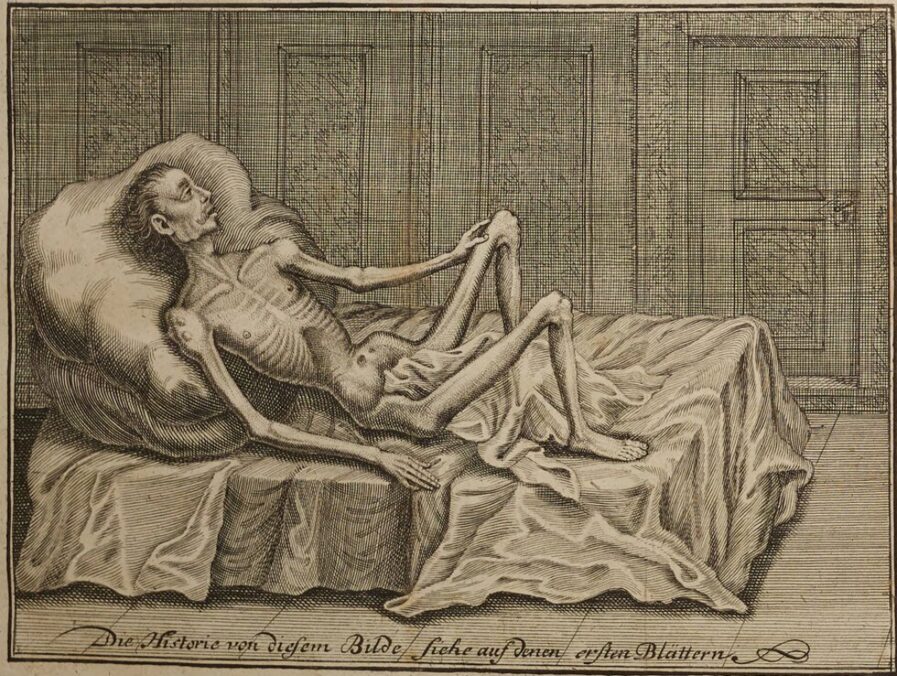

Describes a respiratory condition prevalent among miners, specifically a form of pulmonary tuberculosis. This disease significantly impairs respiratory function, leading to severe breathlessness and loss of speech. It is primarily caused by the inhalation of dust particles in damp mining environments, where the weather remains unchanged due to the dry conditions and solid rock formations.[10]

Bergfertig (adj.) = finished by the mountain

Describes a miner who was so ill that there was no hope for him to be able to work again – literary finished by the mountain due to age or illness.[11]

Hüttenkatze (noun f.) = smelter’s cat

Also known as saturnism, describes a condition associated with the fumes of smelting and particularly lead exposure. It predominantly affects workers in smelting facilities, where they are frequently exposed to and inhale lead vapours. The condition is characterised by persistent abdominal pain, particularly in the navel area, chronic constipation, chest tightness, and other symptoms indicative of gradual lead poisoning.[12]

The specialised vocabulary mining communities developed to describe their occupational illnesses not only reflects the unique health challenges they faced but also underscores the close relationship between their work environment and medical understanding. But how did mining communities manage health and illness, and how was it financed?

Health Management in Mining Sites

In mining communities, medical expenses were a considerable financial burden. The funds carried by the miners’ societies functioned as sick funds and can be understood as “the earliest form of social insurance”. Miners were paid in a “penny box” on a weekly wage and shared it collectively. These funds were used to care for the sick, injured and/or ailing miners. This system also supported their families in the case of death. The funds were used to pay medical practitioners and their fees. The interplay of age, individual constitution, and occupational type significantly influenced the likelihood of securing funding in each case. The “penny box” served as a pivotal account in defining the disease, specifically distinguishing between illnesses attributable to mining activities and those that were not.[13]

In addition to the use of the “penny box” as a form of health management, technical devices were employed to ensure a safe return to the surface. A guidance system utilizing ropes and leather straps was designed for this purpose. Furthermore, the implementation of tunnel supports, lamps, drains, and ventilation shafts was undertaken to enhance workplace safety.[14]

Since the beginning of the mercury mines in Idrija, modern-day Slovenia, in the 1490s, medical practitioners were employed by the mining community. During the 16th century, those offering medical services were not professionals and were usually miners themselves or, in one case, the church organist. In 1639, a bathhouse (Padhaus) is mentioned, which was near a sidearm of the Idrijca river (main river of the town), which was financed by the brotherhood.[15] The treatment expenses were generally borne by the patients themselves, with rare exceptions; costs were covered by the authority. In the mid-17th century, the miners asked the Habsburg Chamber of Inner Austria for a fixed annual salary for their medical practitioner, but did not get an answer to their request. After several requests to the chamber, they eventually granted an appointment to a barber-surgeon with a fixed salary.

Before the 18th century, the community could not afford a university-trained physician. This changed in the mid-18th century when the mines underwent modernisation, which included improvements in health management as a result of the reforms implemented by Maria Theresia of Austria (1717–1780).[16]

Conclusions

Mining communities established their own unique medical environment, partly shaped by the state, due to the specific health impacts of their work. They developed specialized health systems and terminology for their occupational diseases. The nature of their work influenced the language, leading to the creation of terms for job-related illnesses. Early modern scholars were already familiar with the morbi metallici, recognised by ancient authorities, and they shared this knowledge with scholars and physicians visiting the mines. These documented the diseases they observed, and the preventive measures miners took to maintain health. Their recommendations were not limited to the mining sector but extended to all forms of metalwork.

In addition to the services they received from practitioners, miners organised healthcare for themselves by establishing community payments to finance their health infrastructure. With the time and technologies emerging in mining, also the medical awareness and need grew in new directions. Even with technical and medical improvement,s mining remained a health and life-risking business, which maintained its own medical microcosm.