Medieval Uroscopy and the Brain

FORMA FLUENS

Histories of the Microcosm

Medieval Uroscopy and the Structure of the Brain

A Humoral Perspective

Karolina Szula

University of Wrocław

Comèl Grant

The brain was an exceptionally enigmatic organ for ancient and medieval physicians, who developed numerous theories concerning its structure and function. Aristotle described the brain as an organ divided into two chambers and characterized its nature as cold, moist, and bloodless [1].

According to Aristotle, the brain contained no blood vessels and was therefore incapable of supplying itself with blood. This assumption led Aristotle to perceive the brain as largely passive, denying it an active role in the reception of sensory impressions.

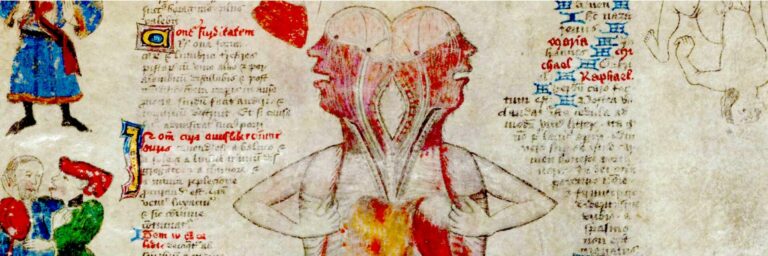

The concept of the brain as a chambered structure was further elaborated and systematized by Galen, who emphasized the harmony of its organisation and distinguished four principal parts. He assigned each part a specific function related to sensory perception and cognitive processing. The anterior part of the brain, composed of two ventricles, was believed to govern reasoning and imagination (sensus communis and fantasia), serving as the site where sensory impressions were received and initially processed. Galen attributed the function of cognition and judgment (cogitativa) to the middle chamber, which was thought to preserve mental traces of perceived objects, even after they were no longer present. The posterior chamber (memorativa), in turn, was responsible for the formation and long–term storage of memories.[2]

The anatomical concept of the brain proposed by Galen became the foundation for medieval medical thought and served as a point of departure for the development of increasingly elaborate theories concerning the organ’s structure. As a result, by the fifteenth century, brain models had emerged that postulated the existence of five or even seven chambers, each assigned specific functions and associated sensory or cognitive faculties.[3]

The medieval conceptions of the brain, however, extended beyond anatomical analysis alone. Medical treatises, particularly the ones grounded in humoral theory, introduced an additional conceptual “map of the brain,” which likewise divided it into chambers, this time corresponding to the four humours: blood, bile, phlegm, and melancholy. This framework played a particularly important role in the literature on uroscopy, one of the principal diagnostic methods of the Middle Ages.

In their efforts to achieve a comprehensive assessment of a patient’s health, physicians examined the pulse, analysed the properties of drawn blood, and paid close attention to lifestyle factors such as hygiene, diet, and daily habits. The aforementioned methods, however, were often considered insufficient for establishing a precise diagnosis, which is why special importance was attributed to the examination of urine. Careful evaluation of its colour, clarity, density, and suspended particles enabled physicians to formulate diagnoses, most commonly within a humoral framework. Deviations from the urine’s natural appearance were interpreted as signs of an imbalance among the humours.

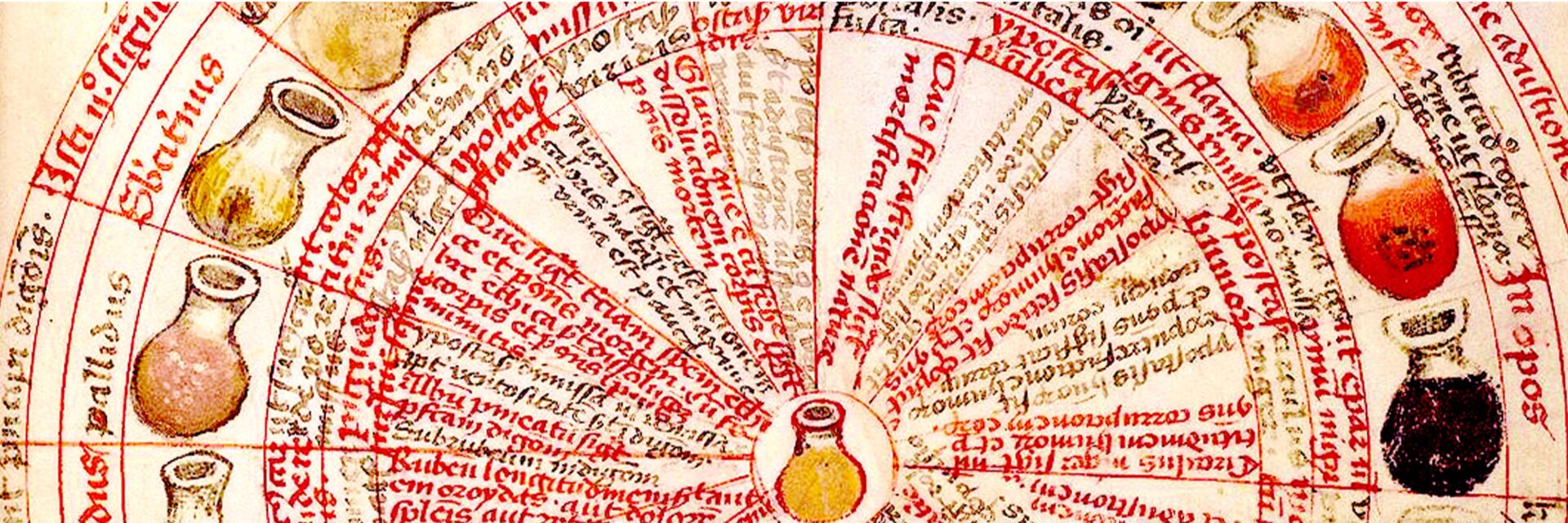

A patient’s urine was collected in a vessel known as a matula or vas urinale. This vessel was conventionally divided into three or four sections, each corresponding to a specific region of the body. The upper part, known as the circulus, was associated with the head. The middle section, situated directly below the ring, corresponded to the chest and its internal organs. The third area represented the organs responsible for digestion and nourishment, including the liver, stomach, and intestines. The lowest part of the vessel – the fundus – was linked to the lower regions of the body, particularly the kidneys, bladder, and reproductive organs.[4]

The excessive production of individual humours was identified through observable changes in the appearance of urine. It was believed that heightened activity of a particular humour could influence the colour of the urine in the upper part of the matula, as well as alter the liquid’s density and consistency within that layer.

Medieval physicians derived the association between the upper part of the urinary vessel and the head, particularly the brain, primarily through analogies of form and spatial arrangement. The section of the vessel known as the circulus occupies its uppermost zone, corresponding to the position of the head and brain in the human body. Its spherical shape was understood to mirror the form of the brain itself.

Isaac of Judaea observed that:

[T]he brain is colder and more moist than all other parts of the body, as all anatomists attest. Hence, it is soft and fluid and therefore difficult to maintain its shape, which is why it is located within the skull. This organ has a spherical shape. The brain is more concealed and situated higher than other parts of the body. It is also filled with air, because its essence is loose and porous. [5]

The aforementioned description suggests that the brain was conceived as a spherical organ positioned at the top of the body. Consequently, the circulus was understood to correspond to the brain in both shape and location, reinforcing its symbolic and diagnostic association within uroscopical practice.

Medieval scholars assumed that the brain contained a substantial amount of air and that substances secreted from it in excessive quantities were likewise highly aerated. In this form, such substances were believed to enter the bloodstream and, through the processes of digestion, to be transformed into urine. According to contemporary theory, urine containing matter derived from the brain would rise to the upper part of the vessel owing to its aerated nature.

This mechanism is described by Gilbertus Anglicus in his commentary on Carmen de urinis by the twelfth-century physician Gilles de Corbeil:

…the excess substance, lifted by the movement of air and set in motion by its own matter, is driven upward and overflows into the upper part of the urine, where it remains near the edge of the vessel. [6]

Karolina Szula completed her studies in Classical Philology at the University of Wrocław. She is currently a doctoral candidate in Literary Studies at the Doctoral College of the Faculty of Letters, University of Wrocław. Her dissertation focuses on preparing a critical edition with commentary of the 14th-century medical treatise De iudiciis urinae written by Thomas of Wrocław. Her research interests include the study of medical manuscripts and the history of medieval medicine in Poland.

The division of the brain into distinct parts corresponding to the four humours is attested in the Carmen de urinis by Gilles de Corbeil. The author observes:

The back part of the brain is diseased due to the pressure of phlegm; a dense purple circulus indicates that blood afflicts the front part; a pale and weak circulus signals that the left side of the brain is affected by phlegm; and the right side of the brain is tormented by acute bile.[7]

Such passages underscore the close relationship medieval physicians drew between humoral imbalance, specific brain regions, and diagnostic interpretation.

These observations are further elaborated by Gilbertus Anglicus in his Commentarius in Aegidii Corboliensis De urinis, where he offers his interpretation of the underlying assumptions. He explains that blood predominates in the anterior part of the brain due to the abundance of veins and arteries, which accounts for the localization of humoral blood in this region.[8] When the circulus reflects excessive activity of humoral blood, it becomes dense and vividly red. Medieval physicians interpreted the density and colour of urine as a consequence of the high temperature and moisture content of the blood.

Gilbertus Anglicus explains the localization of melancholy on the left side of the brain as follows:

The spleen is located on the left side […] so when a certain humour in the spleen or some other lower part [located] on the left side turns into vapours, which are nothing more than fine moisture, these vapours rise and tend towards the head, especially the right side of it, because of their similarity to it. And since [these vapours] are cold in nature, because they were in the lower area [of the organs], and in particular if they were in the spleen, since they found coldness and dryness in the place they were heading for, they quickly return to solidity and thus dominate the left side [of the body] and the left side of the head.[9]

Medieval physicians explained the predominance of melancholy on the left side of the body by the position of the spleen, which was understood to be dry and cold, characteristics naturally associated with this humour.[10] The spleen’s location implied that the entire left side of the body shared these properties. According to contemporary theory, vapours emanating from the spleen ascended to the left side of the brain, where they encountered an environment compatible with their nature. Consequently, the left hemisphere of the brain was considered the principal seat of melancholy.

According to Gilbertus Anglicus, the right side of the brain was regarded as the seat of the choleric humour because the entire right side of the body exhibited properties consistent with the nature of bile. He explains:

The right side is warmer by nature because the liver […] and the heart […] are located there, which makes the right side warmer. Therefore, when vapours rise from the lower right parts, and especially if they are warm, they tend to move towards the right [side]. [11]

The liver, situated on the right, was perceived as a warm and dry organ responsible for producing bile, while the heart served as an additional source of heat in this region.[12] Based on this anatomical and humoral arrangement, medieval physicians concluded that the right side of the body was naturally characterised by elevated temperature and dryness. Consequently, the bile conveyed to the brain in the form of vapours was thought to ascend to the right hemisphere, where conditions were favourable to its inherent properties.

Gilbertus Anglicus justifies the location of the phlegmatic humour in the posterior, occipital region of the brain as follows:

[…E]specially the rear part, which is most suitable [for this humour], should [be occupied by phlegm], […] the back part is a vessel for phlegm, therefore, due to this necessity, the back part is most [its] seat, because the heart and liver radiate less from this part of the back and spine than from the front [part], because the digestive organs are located in the front. [13]

The analysis of medieval conceptions of the brain’s structure and function reveals the extent to which medical thought at the time remained anchored in humoral theory and a symbolic-analogical understanding of the body. Uroscopy, one of the principal diagnostic methods, enabled physicians to construct intricate models linking organs and humours. Within this framework, the four-part division of the brain emerged, corresponding to the dominance of particular humours and their associated thermal and moisture properties. Although the interpretations presented in these treatises were based on assumptions far removed from modern anatomical knowledge, they constituted an important stage in the development of European medical thought.