Reshaping Vesalius’ Legacy

FORMA FLUENS

Histories of the Microcosm

Reshaping Vesalius' Legacy

The "Fabrica" and the "Epitome"

a Hundred Years after their Publication (1604, 1617, 1642)

Sabrina Engert

University of Wuppertal

Santorio Fellow

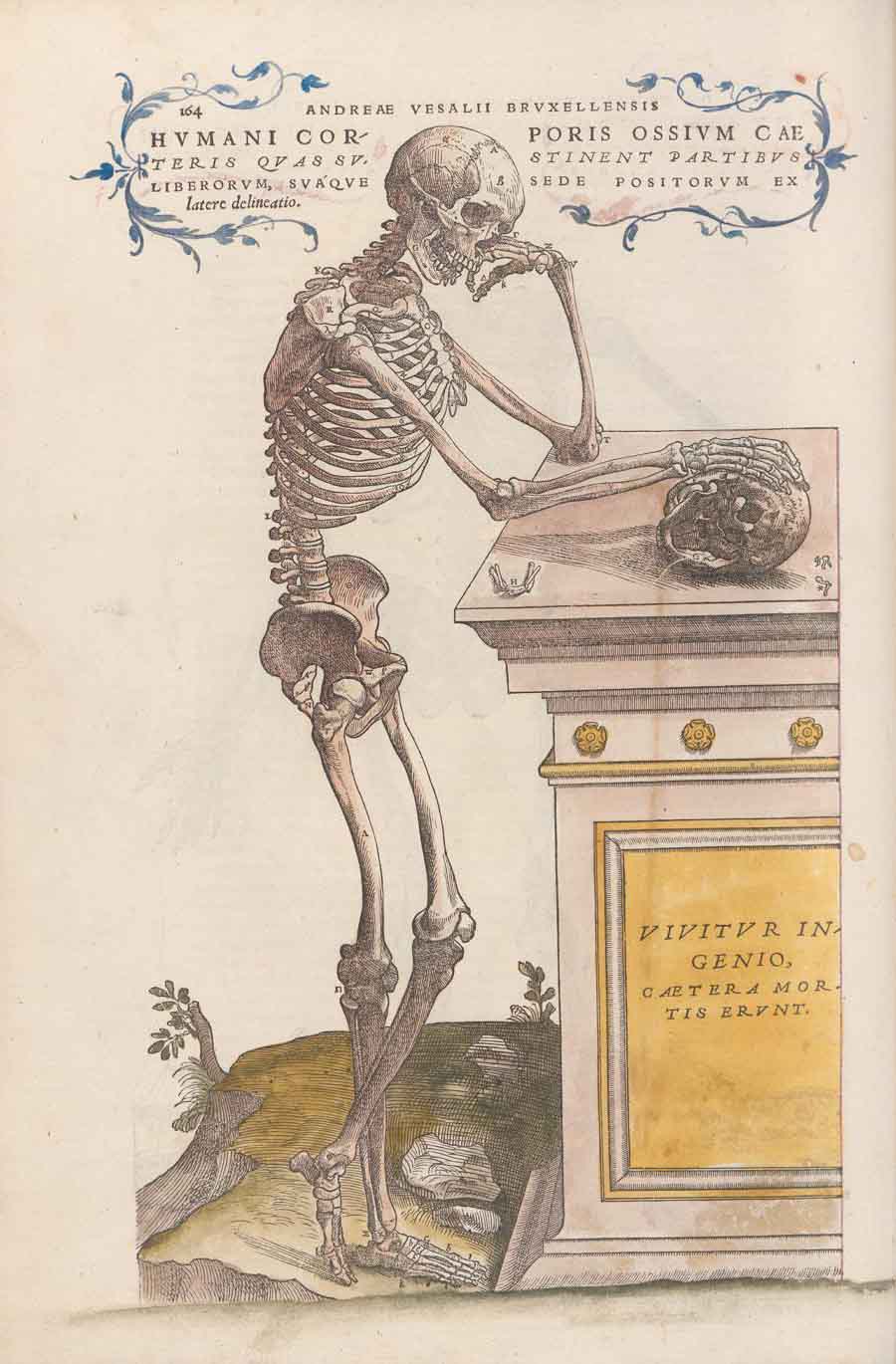

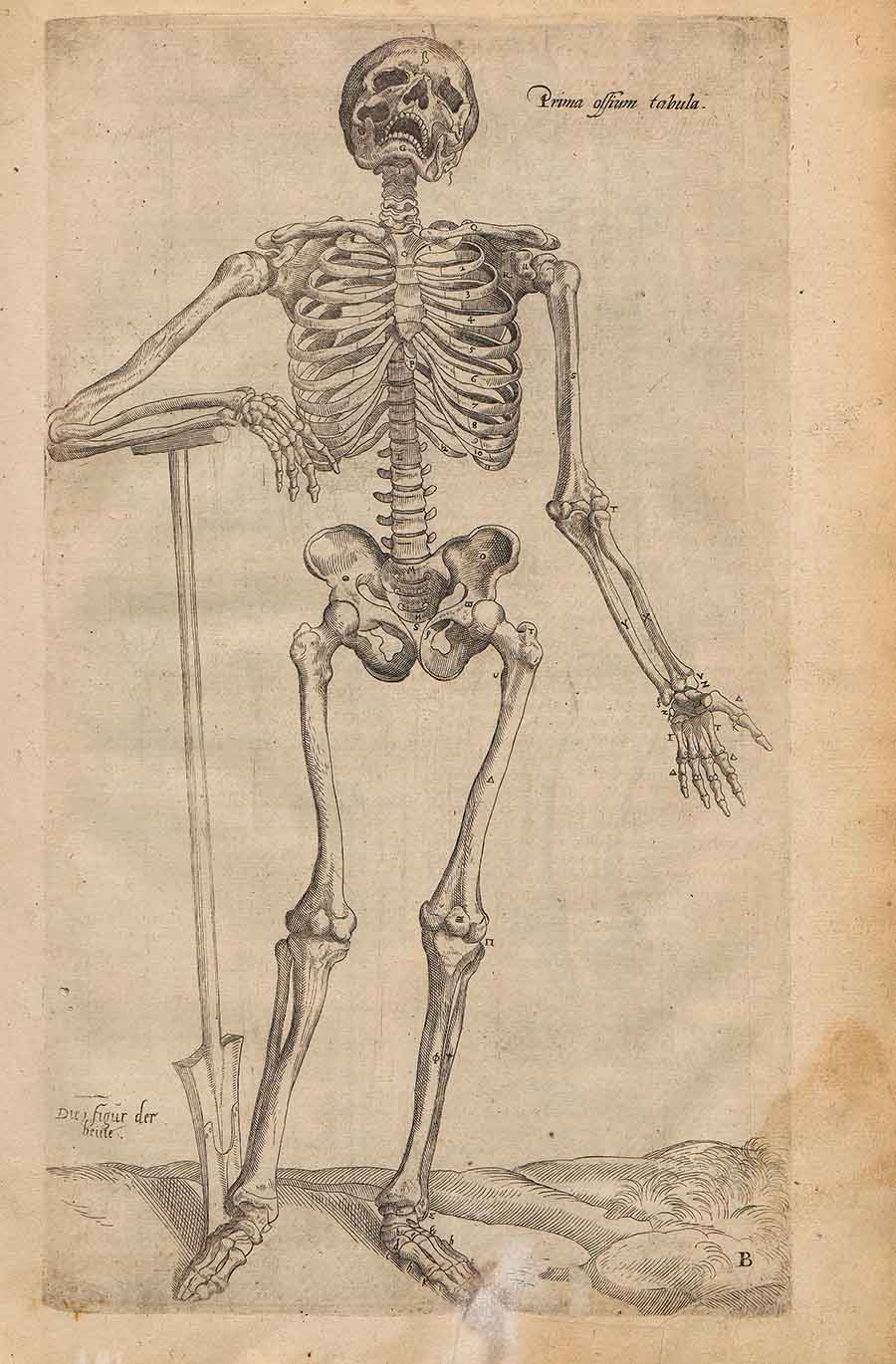

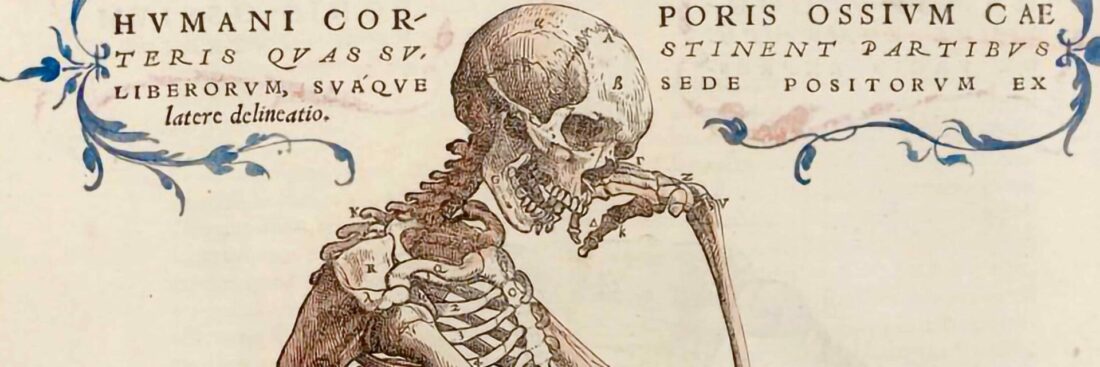

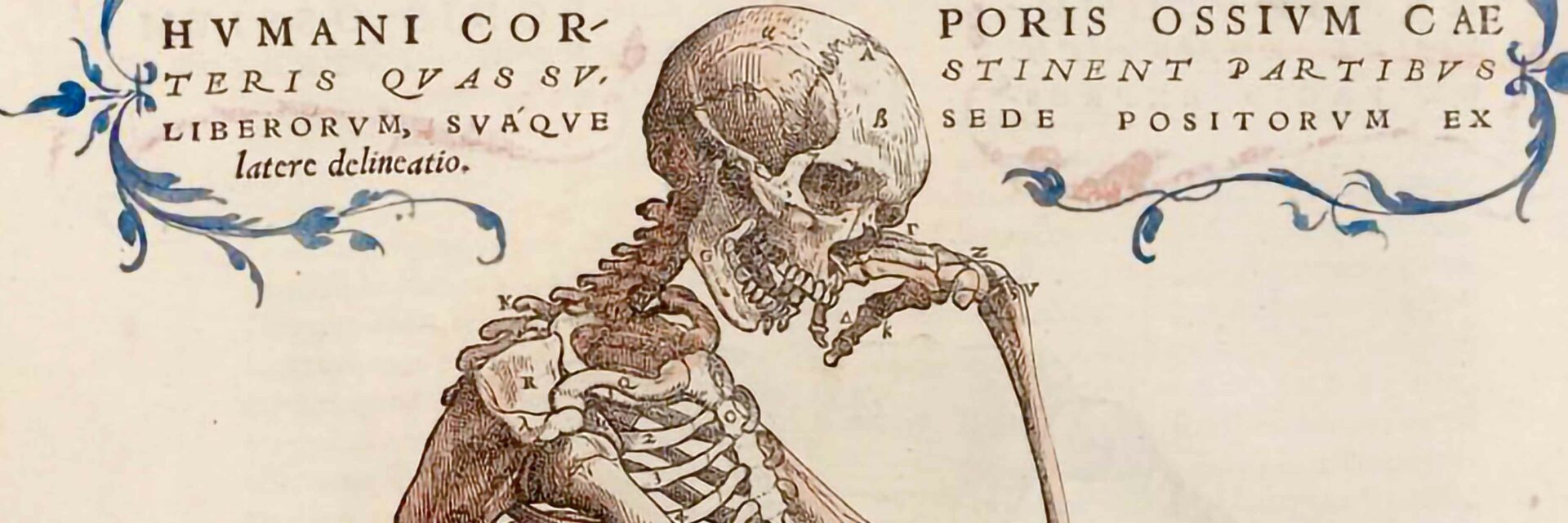

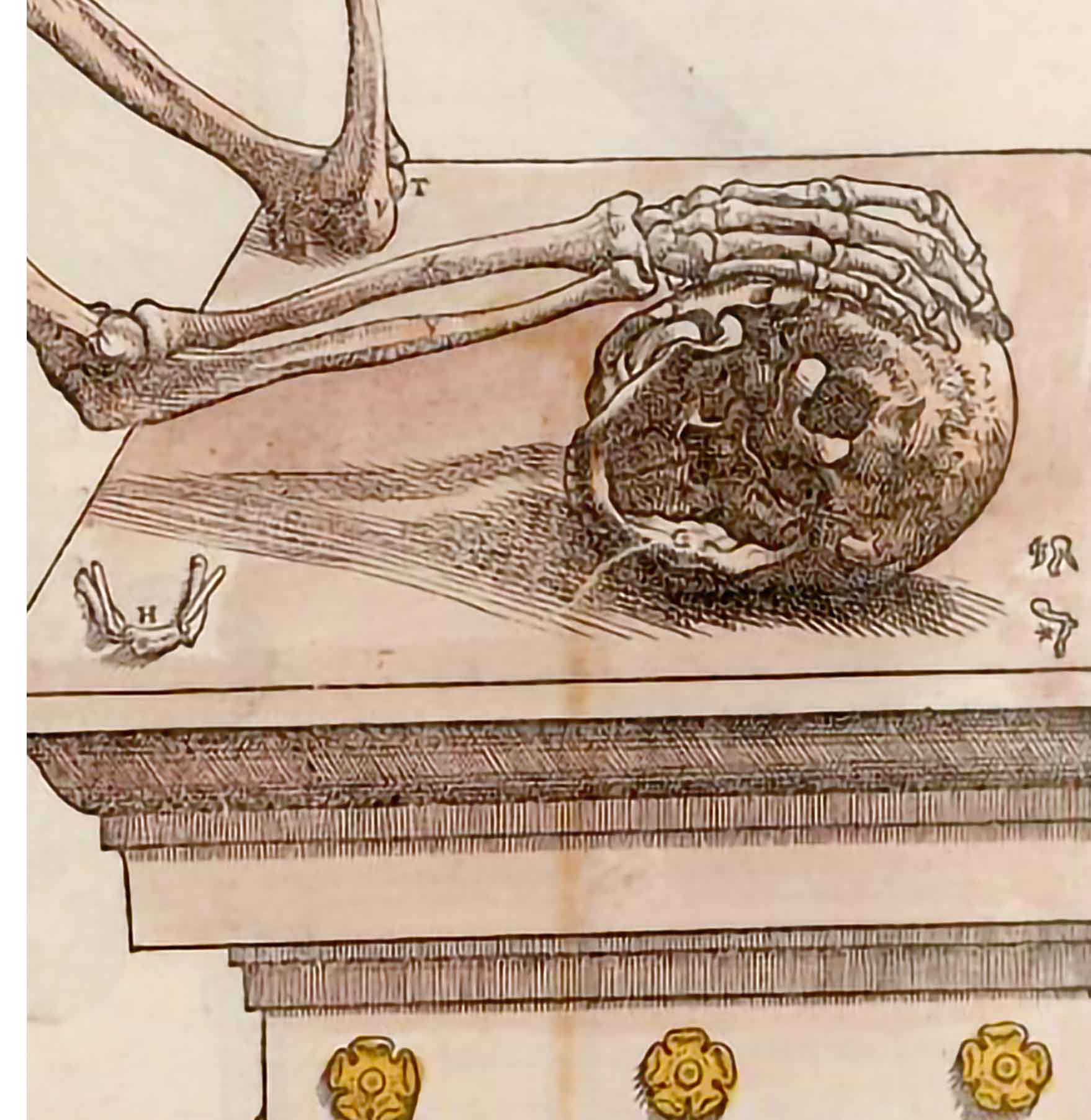

Vivitur ingenio, caetera mortis erunt (“One lives through the spirit, everything else is mortal”) – this epigraph is engraved on a pedestal [Figure 1] beneath a skeleton resting its head in its hands, as if lost in thought like a person still alive. For Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), this image proved prophetic: he remains a central figure in the development of anatomy in early modern Europe, often associated with the so-called “scientific revolution”. However, it is important to view this revolution less as a sudden break and more as a gradual process. Recent research underscores the continued interest in Vesalius’ life and works.[1]

His famous anatomical atlas De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (from now on: Fabrica) is considered an unprecedented synthesis of art and anatomy, and a milestone in the visualization of scientific knowledge.[2]

As mentioned above, both Vesalius as an anatomist and his Fabrica and the De humani corporis fabrica librorum Epitome (= Epitome) represent milestones in the history of medicine and anatomy. In the 16th and 17th centuries, he became an enduring scientific authority[3] – even after his death in 1564. Nine years earlier, he himself had published a second edition of the Fabrica, nonetheless, his works proved so valuable for anatomical studies that soon new re-editions were necessary. Since Vesalius was no longer able to authorize or supervise the printing process, the following questions arise: How were the Fabrica and Epitome published and printed after Vesalius’ death? Which passages were omitted, altered, or retained? Examining the history of its reception provides interesting insights into the circulation of knowledge and the traditions that shaped the anatomical sciences in early modern Europe.

About the "Fabrica"

Andreas Vesalius is known as an advocate of empirical observation and frequently honored as the “father of modern anatomy”. He played a crucial role in the scientific transformations of the 16th century. Viewed from a broader perspective, Vesalius fits perfectly into the intellectual movement of Renaissance-Humanism: his Fabrica, published in 1543, reflects the rethinking process of classical authorities such as Galen and Hippocrates. Similar to the former, Vesalius emphasized the importance of dissection as an essential skill for anatomists, but he also sought to move beyond text-based teaching toward sensory-based learning.[4]

The frontispiece of the Fabrica [Figure 2] illustrates this very idea: it depicts a fictional dissection in the midst of a crowded anatomical theatre, underscoring Vesalius’ claim that dissections were central to anatomy and of great interest to a broader public.[5] Beyond this iconic frontispiece, the Fabrica brought together a wide range of discoveries and shaped anatomical education for generations. Due to its scope and size, however, the Fabrica served more as a prestigious reference work than a practical textbook for students.[6] Vesalius dedicated his work to Charles V, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, whose court-physician he would later become. In an effort to make the material of the Fabrica more accessible and affordable for students, Vesalius also published the Epitome, a condensed version of the Fabrica, which he dedicated to King Philip II of Spain.[7]

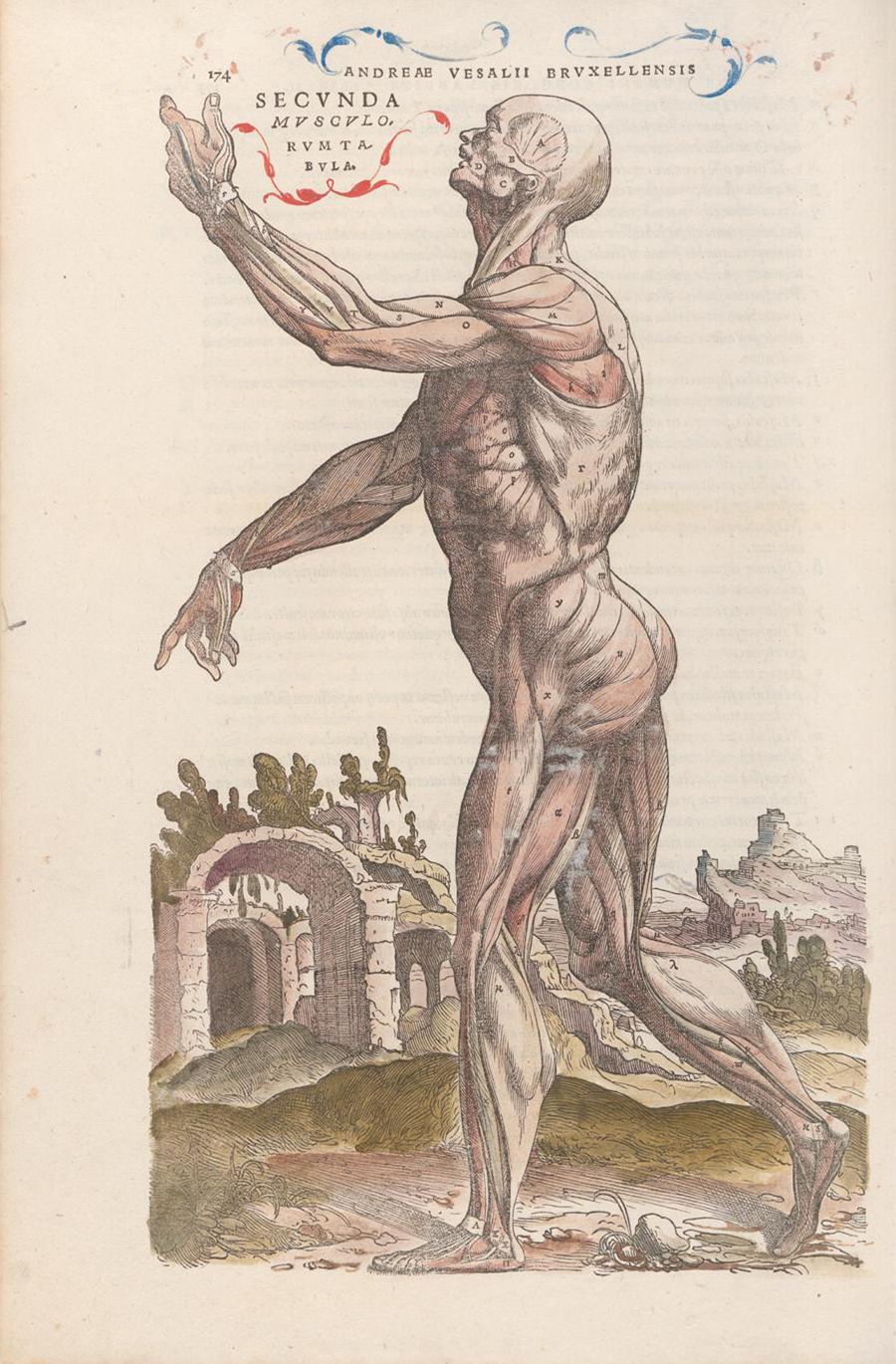

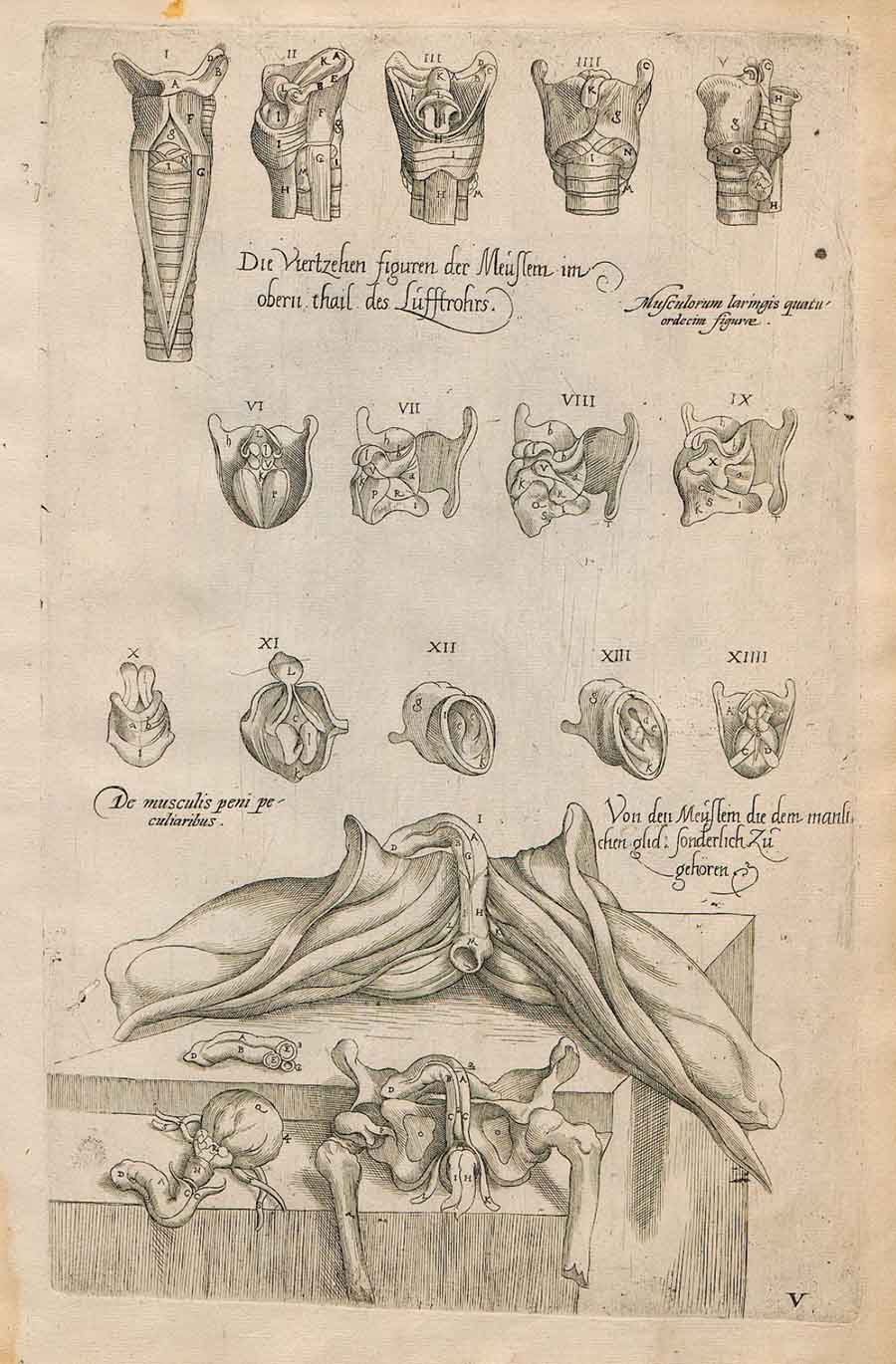

One of the main reasons for Vesalius’ lasting influence on anatomy lies in the extraordinary illustrations of his atlas,[8] which comprises more than 700 pages. The famous “muscle men” [Figure 3] remain celebrated not only for their anatomical detail but also for their lifelike poses and dramatic staging, bridging the boundary between art and science,[9] exemplifying the early modern endeavor to visualize and thereby communicate complex knowledge.

Re-Editions of the "Fabrica" ...

The Fabrica and the Epitome of Vesalius were (re-)edited several times. In 1555, Vesalius prepared a second edition for which he made minor changes to the frontispiece and the text.[10] But what did the re-editions look like once Vesalius was not involved any longer? Were they simply old books in new covers, or did they serve distinct purposes? The following three examples from 1604, 1617, and 1642 illustrate different editorial strategies.

Only four years after Vesalius’ death in 1564, a first re-edition of the Fabrica was published in Venice, showing an increasing interest in and demand for his works so shortly after his death. However, the first re-edition considered here was published in 1604 by the Venetian brothers Giovanni Antonio and Giacomo de Franceschi. They reduced the original roughly 700 pages to 510 pages in a smaller format and added anatomical tables compiled by the physician Paulinus Fabius, offering insights into ancient anatomy. In their preface, the Franceschi brothers explain their motive for abridging the text, namely, with several tables added, to make it more accessible and attractive to readers.

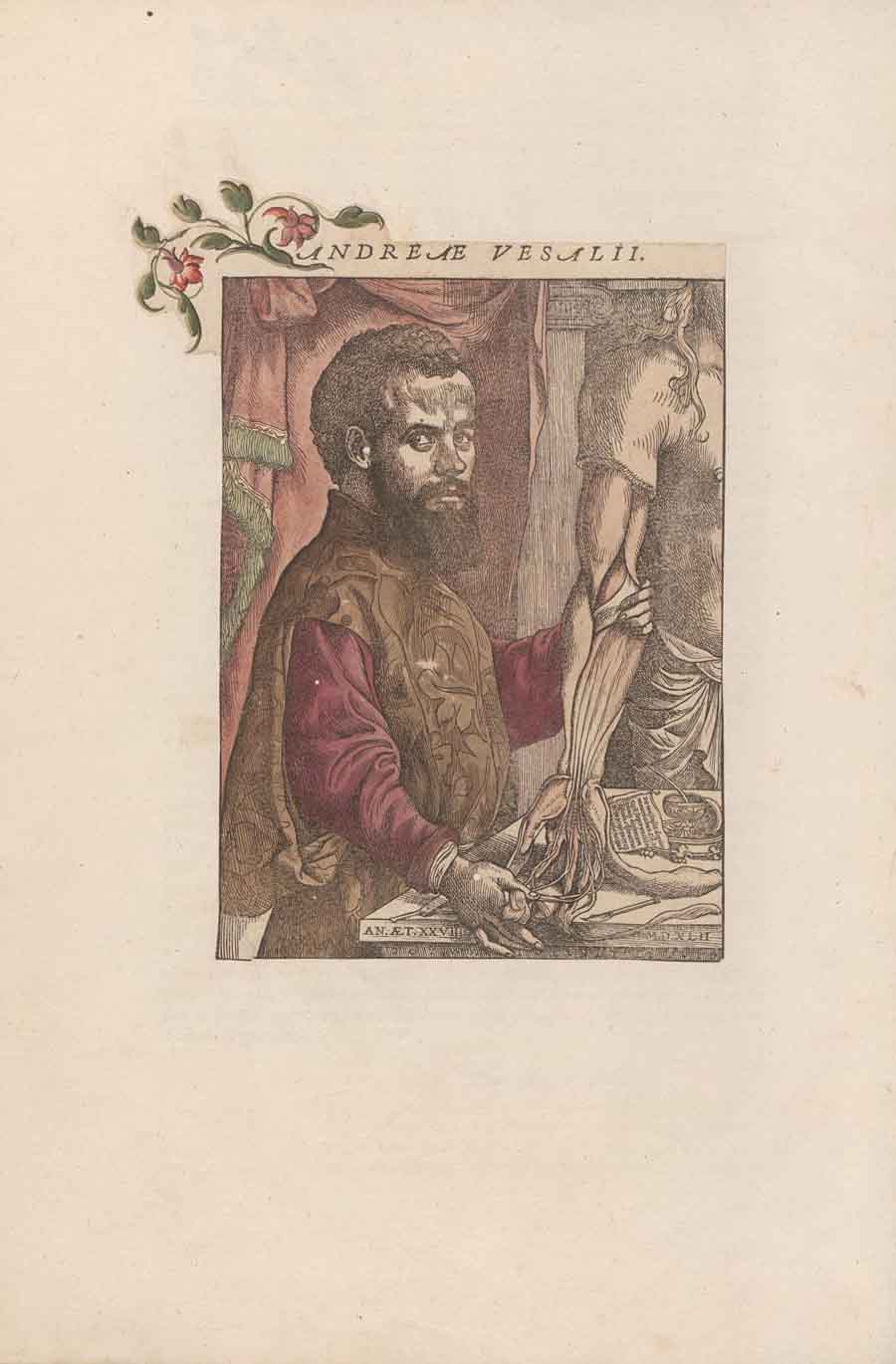

The re-edition from 1604 also included a new engraved title page, a dedication, the preface, a Greek epigram with a Latin translation, an index, the printing privilege, and an introduction to the anatomical tables, followed by the tables themselves. Notably, they left out the portrait of Vesalius in which he had depicted himself as a practising anatomist [Figure 4]. Otherwise, the structure of the seven books remains unchanged.

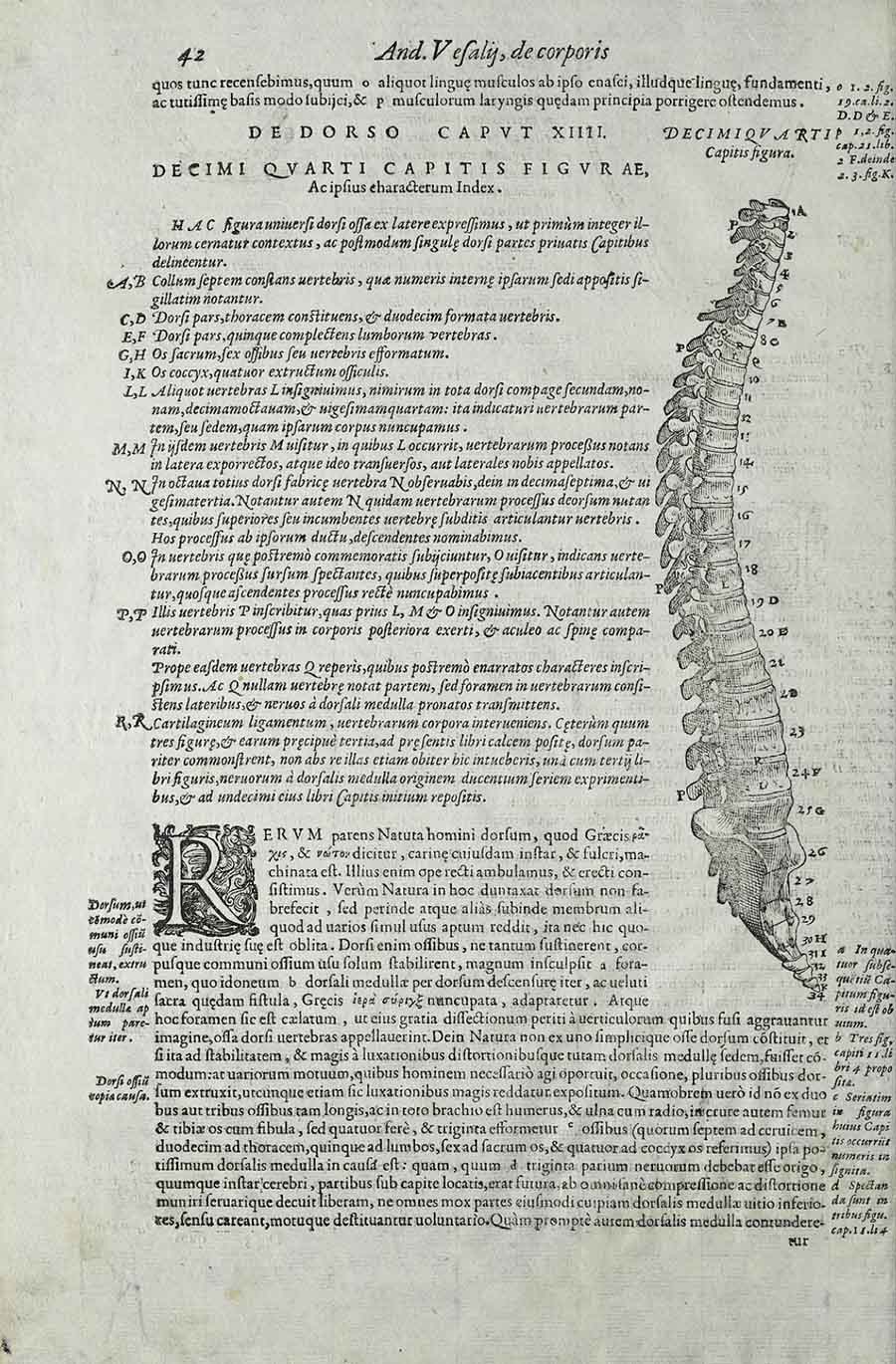

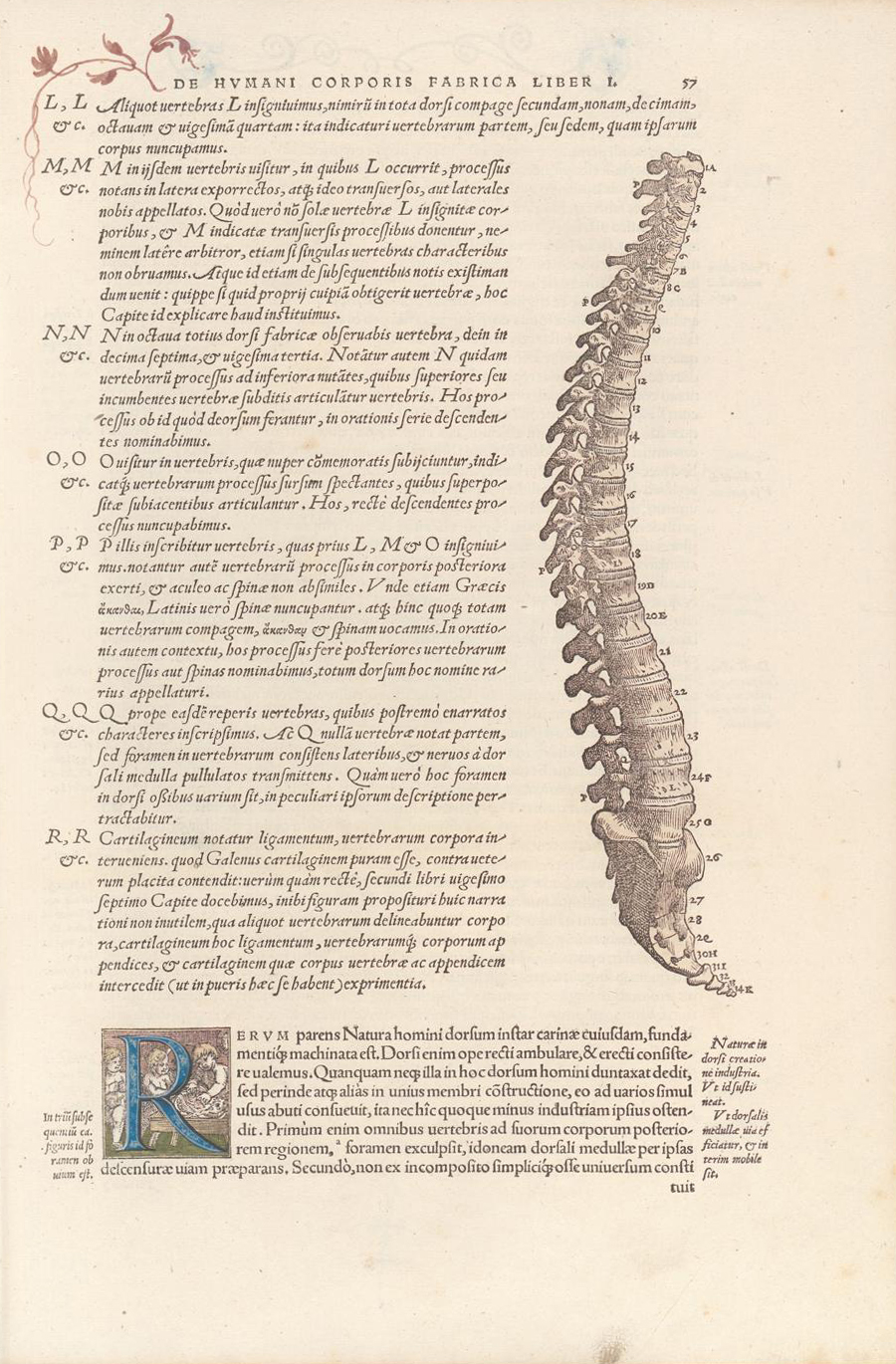

A closer comparison of the woodcuts from 1604 [Figure 5] with those of 1543 [Figure 6] reveals both continuity and change: on the one hand, the overall layout closely resembles the original, while on the other hand, the ratio of text to image often differs. In the 1543 edition, the chapter about the spine begins one page earlier, whereas in the 1604 re-edition the text is condensed, with the chapter starting on the same page as the corresponding illustration.

This shortened version of the Fabrica concludes with a fifteen-page set of anatomical tables, arranged as follows: anatomy of: the bones, the external parts, the internal parts, and the uterus according to Soranus.[11] These tables serve as an independent work appended to the re-edition, including their own title page as well as a separate preface. The title page credits the Franceschi brothers as printers, while the preface, addressed to the medicinae studiosis, presents the tables as instructional material designed to facilitate the understanding of Vesalius’ work.

Sabrina Engert is a PhD candidate and researcher in the history of science and technology at the University of Wuppertal. Her research focuses on the significance of authorities, traditions and legitimisation in the so-called Scientific Revolution. In her thesis, she examines the transformation of scientific authorities in the fields of astronomy and anatomy in early modern Europe. Apart from that, Sabrina is also interested and engaged in various projects concerning the history of orreries, especially 20th-century optical planetariums. She is currently working at the Interdisciplinary Centre for Science and Technology at the History of Science and Technology Department.

In conjunction with the purpose of the re-edition stated in the preface, the intention becomes clear: this 1604 re-edition was aimed primarily at students rather than professional anatomists.

...and the "Epitome"

The next re-edition concerns the Epitome, the abridged version of the Fabrica, both of which Vesalius originally published in 1543. In 1617, a new re-edition appeared in Amsterdam, edited by Heinrich Botter. Seventeen years earlier, Botter had already supervised a re-edition of the Epitome in Cologne,[12] but this time Johannes Janssonius, who primarily produced globes and cartographic works, was indicated as the printer.[13] Botter himself was the personal physician to Count William VI and died in 1617[14], probably a few months before the publication of this re-edition.

This re-edition’s title explicitly emphasizes its dedication to students. The paratexts include an image of an unidentified man, a decorative title graphic, a dedication dated 7 September 1617, to the consul of the Cologne Senate, a copy of Vesalius’ portrait, an image of Adam and Eve, and approximately 88 pages of text accompanied by 38 pages with illustrations. In addition to the Epitome itself, the re-edition also contains a register that names and contextualizes the anatomical illustrations.

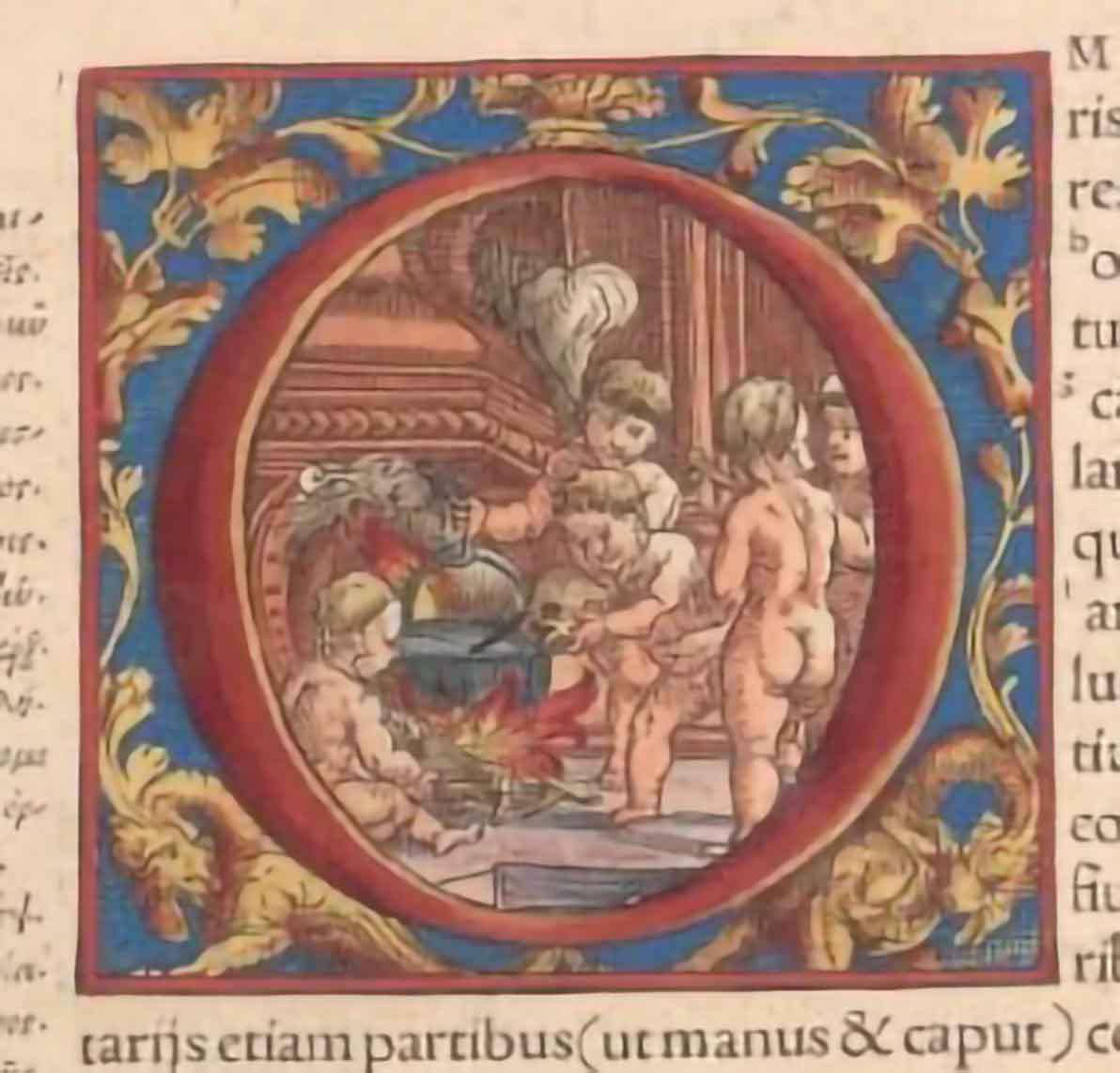

The woodcuts are closely modelled after those from 1543. While, for example, the decorative initial from 1543 [Figure 7] is more elaborate, the corresponding version from 1617 [Figure 8] remains very similar. Particularly noteworthy are the German inscriptions that appear on some of the anatomical illustrations: in Figure 9, for instance, a skeleton is labelled not only Prima ossium tabula in Latin on the right but also “Die 1. figur der beine” in German on the left.[15] Although printed in Amsterdam, the dedication to the consul of Cologne suggests that these German captions may have been intended for him.

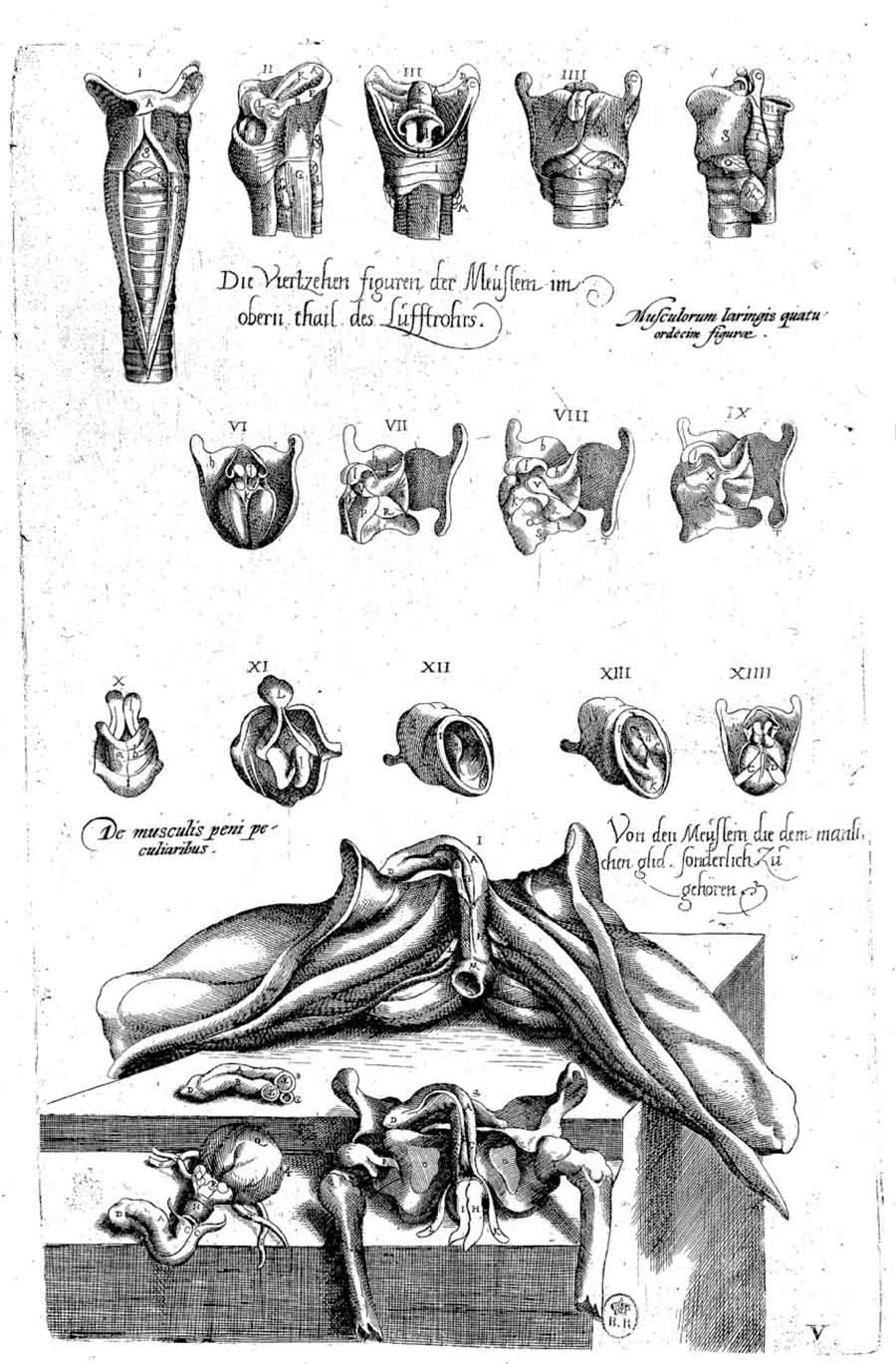

Similar to the 1543 Epitome, the 1617 version largely adopted Vesalius’ text, albeit with minor changes. Yet, this re-edition is more expansive than the original: comprising many anatomical illustrations, some of which were originally a part of the Fabrica. By placing multiple images on a single page, Botter and Janssonius created space to incorporate additional plates. As a result, a hybrid of the textual framework of the Epitome enriched with an extensive visual component from the Fabrica emerges. This synthesis is further underscored by the inclusion of Vesalius’ portrait, which was originally a part of the Fabrica, now appearing as a newly engraved copy.

The final re-edition dates from 1642 and was published almost a century after the original Fabrica and Epitome. Like the 1617 edition, it was printed in Amsterdam by Johannes Janssonius, but this time the editor and author was Nicolaas Fonteyn (Nicolai Fontanus), a physician from Amsterdam. Relatively little is known about his life (c. 1589–1667), though he also published his own anatomical works.[16]

In the letter to the reader, Fonteyn explains that Janssonius had approached him for this re-edition of the Epitome to enrich it with his own observations and commentary. Fonteyn fulfilled this request: following each chapter, he added his Nicolai Fontani Annotationes, accompanied by anatomical illustrations and an index. When comparing the plates from the 1617 and 1642 editions (e.g. Figures 10-11), it becomes apparent that Janssonius reused several copper plates as the German translations next to the anatomical illustrations are still visible, despite Fonteyn being Dutch and dedicating his work to the Dutch prince, therefore making the German translations unnecessary; if anything, one might have expected Dutch equivalents.

This edition showcases that it was not only Vesalius’ Epitome that was being (re-)printed, but also Fonteyn’s own scholarly contributions. The 1642 volume represents a synthesis of an authoritative 16th-century text with new 17th-century commentary—an updated critical edition that reveals how Vesalius’ work continued to be reshaped nearly one hundred years after its first publication.

Conclusions

The re-editions of Vesalius’ Fabrica and Epitome in 1604, 1617, and 1642 reveal not only how his work was preserved, but also how it was reshaped in the century after its initial publication. The Franceschi brothers abridged the Fabrica to make it more accessible, supplementing it with anatomical tables, while almost turning it into a textbook for students. Heinrich Botter expanded the Epitome by integrating images from the Fabrica and visually enriching its contents even further. Finally, Nicolaas Fonteyn enhanced the text with his own annotations and commentary, creating a hybrid version of his own ideas and those of Vesalius. These editions demonstrate that, while Vesalius’ authority remained strong, his work was continually adapted to meet the needs of new audiences, new demands, and new discoveries. Rather than being mere reproductions, these re-editions functioned as interventions in the ongoing circulation of anatomical knowledge. Nearly a century after their initial publication, the Fabrica and Epitome thus retained their status as cornerstones of anatomy, while simultaneously evolving in response to changing intellectual and educational contexts.