Drinking Water Cures and the Body in 17th-Century Tuscany

FORMA FLUENS

Histories of the Microcosm

Drinking Water Cures and the Body in 17th-Century Tuscany

Beth Petitjean

Saint Louis University

Today, visitors to Tuscany know the importance of drinking water to stave off dehydration during the hot and humid days of summer. What might be less known is that some visitors in the seventeenth century went to Tuscany specifically to drink water—the natural mineral water available at the many springs dotting the countryside. At the Bagni di San Casciano in southern Tuscany, Doctor Giovanni Bottarelli prescribed specific drinking therapies to treat patients for a range of conditions including kidney stones, asthma, stomach problems, and neurological conditions. In his 1688 treatise, De’ Bagni di S. Casciano, Bottarelli described the medicinal qualities of the springs, offered advice for how to take the waters, and documented over seventy patients he treated during his tenure as the resident physician at the baths.

Of the twelve springs at San Casciano, only three were used for drinking therapies: Ficoncella, Grande, and Bosso. According to Bottarelli, Ficoncella water “purges excess humors, revitalizes loose parts, cuts through viscous material, and expels humidity,” thanks to its combination of minerals including iron, alum, and vitriol. Water from the Bosso spring contained alum and copper, which Bottarelli deemed as good for any cold and humid condition, especially those of the head and stomach. Grande—the largest of the springs—contained alum, sulfur, and copper, which made the water appropriate for drying and warming while also drawing out impurities and dissolving obstructions in the body.[1]

Bottarelli’s patient observations reveal the centrality of drinking water to balance nearly every humoural temperament and to cure many different conditions. For example, Bottarelli treated a 36-year-old man from Cortona who visited the baths in July 1680. The doctor determined the man had a bilious and sanguine temperament and was suffering from excessive heat in his body. He prescribed drinking 8-12 libbre of Ficoncella water first thing in the morning each day for fifteen days; by the end, the man was feeling much better.[2]

The prescription for drinking water was similar in other cases. In 1681, another man from Cortona arrived complaining of stomach pain. This man had a bilious and melancholic temperament, as well as a liver obstruction, but after fifteen days drinking Ficoncella water, Bottarelli observed the patient returned to a state of perfect health.[3] The following year, a man suffering from nephritis with gravel, stones, and viscosity in his urine arrived from Cartocceto. He had a sanguine temperament, was very pale and in great pain from his condition. Bottarelli prescribed drinking Ficoncella water; the man passed a large and spongey stone on the third day, with more gravel passed over the following days. By the fifteenth day of drinking, the stones were gone, and the color had returned to his face.[4]

Beth Petitjean earned her PhD in History in December 2019 from Saint Louis University. Her dissertation, “The Baths and the Medici: Taking the Waters in Grand Ducal Tuscany, 1537-1790,” reconstructs and analyzes thermal baths as significant features of early modern medical, scientific, and court cultures. Her most recent article, “Sustaining Thermal Water in Early Modern Tuscany,” appeared in the Special Forum Issue: Ecology and the Environment in World History Connected 18.2 (June/July 2021). She has held short-term fellowships at the Huntington Library, the Linda Hall Library, and the National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Institute at the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library. Beth has worked as an Instructor at Missouri University of Science and Technology and St. Louis Community College and is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor at Saint Louis University where she teaches history of medicine courses.

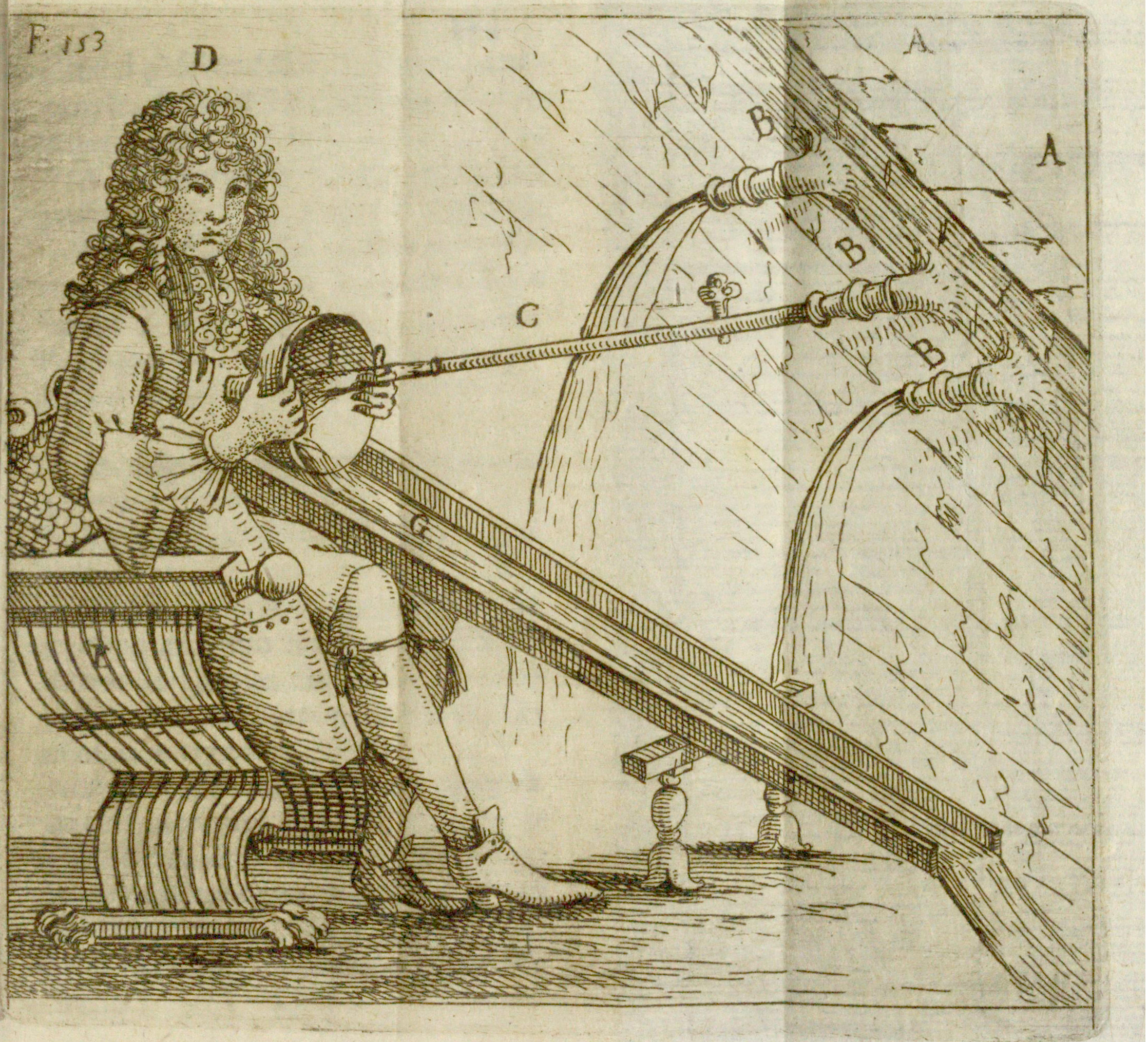

Bottarelli resorted to a combination of treatments with the waters of Grande and Ficoncella when a case proved difficult. The doccia per lo stomaco was a shower treatment with mineral water applied externally to the patient’s abdomen (see Fig. 1). Bottarelli recorded the case of a 25-year-old man with a phlegmatic temperament suffering from stomach pains and dysentery who arrived in 1680. Bottarelli prescribed sixteen days of drinking Grande, Ficoncella, and Bosso waters first. Then, he added stomach showers—one in the morning and one in the evening with each shower lasting up to an hour—for five days at Bagno Grande before taking sixty more stomach showers at San Giorgio, one of the other springs in San Casciano. Bottarelli recalled that he received a note from the man several weeks later saying that he remained healthy after his month-long treatment at the baths.[5]

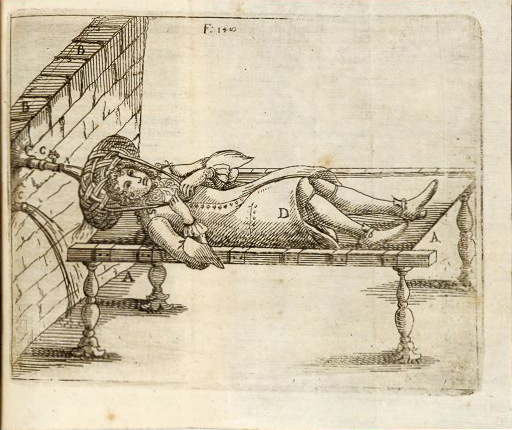

The doccia della testa (see Fig. 2) was another shower option used in combination with drinking therapy. As the name makes explicit, this treatment was designated specifically for conditions related to humoral imbalances related to the head. For instance, a 40-year-old man from Toscanella arrived in July 1680 seeking treatment for asthma. Bottarelli determined that the man’s condition was caused by excess humidity that descended from his head into his lungs. The treatment plan included sixteen days of drinking water at Grande, Ficoncella, and Bosso, followed by ten days of the doccia della testa treatment, with each twice-daily shower lasting between thirty and sixty minutes; at the end of the treatments, the man left breathing easily and free from asthma.[6]

Very few female patients appear in the pages of Bottarelli’s treatise, but those that are mentioned indicate that women partook of similar treatments. For example, a 20-year-old woman suffering from tremors in her head arrived from Camporsevole in July 1681. Bottarelli prescribed sixteen days of drinking therapy, followed by sixty doccie della testa with Santa Maria water (another bath in San Casciano) and then 120 doccie della testa at Bagno Grande. The lengthy treatments required the woman to stay in San Casciano for over two months, although Bottarelli omitted mentioning whether the treatments were successful.[7]

The end of summer meant the end of the bath-going season for each year. However, the good outcomes Bottarelli achieved encouraged patients to return in subsequent years, such as the Cortonese man with the sanguine temperament who returned in 1681 for another treatment to maintain his good health. Bottarelli’s treatise shows us that drinking water during the summer has been an important health practice for centuries.